Seeking Identity with a T-Shirt: Uniforms in the Martial Arts

The Varieties of Uniformity

My Monday evening study-group just passes a milestone. Somehow it never even occurred to me that this was on the horizon, though I was the one who (inadvertently) set things in motion. An acquaintance organizes a local street festival and she generously offered to give our group booth space and some time for small demonstrations. I accepted her offer and, as I was starting to pull things together, decided that we could really use some T-shirts. Nothing all that formal, just enough to let people know who we were.

Many martial arts communities have standardized, highly “traditional,” uniforms. The elements of the Chinese martial arts world that I spend most of my time with do not. The Wing Chun school where I did most of my training even managed to resist the social pressure to adopt a system of colored belts or sashes. The only formal ranks we have are student, assistant instructor and Sifu. Likewise, we all trained in T-shirts and jogging pants. Some people wore shirts with the school’s logo, often the mementos of a previous seminar or summer-camp. The more vintage such a shirt was the more respect it commanded. But most people just wore random athletic clothing. Matching T-shirts were generally reserved for some sort of public event.

So, with a public event of my own on the horizon, it seemed high-time to order a bunch of shirts for my training group here in New York. That announcement unleashed a fair amount of enthusiasm and my students have spent the last few weeks designing images, selecting colors and comparison shopping for price quotes. These shirts have taken on a much more complex set of meanings than simply being a way to signal who we are in a crowd. In a way its all very predictable. Everyone in this group has been working hard for months, and the class is developing into a tight knit community. I suspect that all of this emotional energy has been invested into the process of buying these shirts. I hope they end up looking great as they now have a lot to live up to!

All of this got me thinking about the role of uniforms in the martial arts, and the differences that we see between styles and communities. Why is the training gear in some arts more formalized than others? What are they attempting to signal, and to who? Where did our notions of the “proper” martial arts uniform come from, and why does it change over time?

I suspect that pretty much everyone who practices martial arts wears a uniform, even if they are not aware of it. This does not mean that all uniforms have the same meaning, or that they come from the same place. Indeed, there is a huge amount of variation in the social construction of training clothing. While my Sifu’s school never had any sort of rules about training clothing, it was clear that a well-understood informal dress-code was in effect. Everyone wore nearly identical darkly colored T-shirts and jogging pants. Nor are they alone in this. As I have gone to various seminars and visited multiple schools, that same unspoken dress code seems to have spread quite widely throughout the Wing Chun community. From a sociological standpoint such a widely shared “uniform” is quite interesting, even if few of these communities would admit to having a “dress code.”

Still, it is the differences in the ways that schools approach this aspect of material culture that is truly revealing. To simplify what is a complex topic, one might think of any uniform as occupying a distinct place within a theoretical cube defined by three axis. The vertical axis might represent the question of centralization. Is your uniform defined and enforced by a central authority (high), or is it more a matter of group culture (low)?

The front axis can be thought of representing a uniform’s symbolic vs. functional attributes. Victor Turner noted that most material artifacts have both a practical and symbolic value. Both are always present, but possibly not in the same degree. The stylized helmets worn in Kendo suggest a high degree of practicality, whereas the stripes of colored tape that adorn the Taekwondo belts of my many nieces and nephews would seem to function only as motivational tools.

The back axis of our graph might be thought of as measuring the degree of individual expression that one sees in a uniform. They function as markers of community identity precisely because of their ability to make everyone appear “uniform.” And yet they must also express more individual characteristics, such as one’s rank or position in a community. On one end of the spectrum these markers may be kept to an absolute minimum (perhaps just a belt color). On the other side of the spectrum we might find the highly personalized armor favored by various HEMA fighters, or the explosion of patches on some Kempo uniforms. One might also think of this axis as a measure of the degree to which consumer power can be used to personalize one’s image within the fighting community.

Any of these uniforms can tell us, at a glance, where someone stands within the larger martial arts community. Kendo players do not look like silat students, and they all appear quite different from the guys who gather for “open mat night” at the local BJJ school. Yet I suspect that if we think about these uniforms in terms of the three axis of analysis outlined above, we might come up with some unexpected hypothesis about the differing social needs and functions that each of these communities fulfills, based on the sorts of material culture they exhibit. Alternatively, we might take a single school and think about how its uniform conventions have changed over time as a way of understanding that style’s unique historical evolution.

The Japanese and Chinese Cases

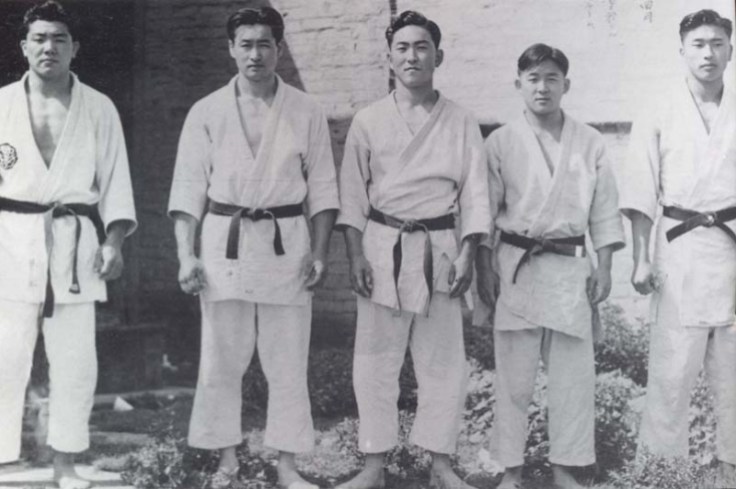

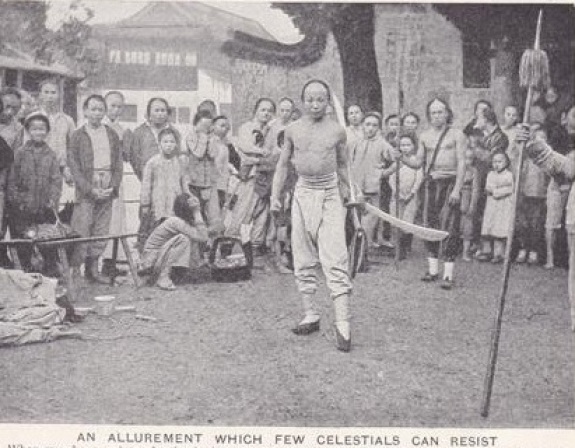

Perhaps there is no more striking example of this possibility than to consider the large archive of vintage photographs that I have collected on this blog over the years. A thought occurred to me as I looked over the various newspaper photographs, tourist pictures and postcards that I have posted. About half of these images show Chinese martial artists, and most of the rest focus on Japanese subjects. Yet instances of easily identifiable uniforms are not equally distributed across these two groups.

Looking at just my collection of vintage (pre-WWII) postcards I noted only one example where civilian Chinese martial artists could be seen wearing a martial arts training uniform. And even in that instance the significance of their clothing was probably lost on Western viewers as not everyone in the picture was wearing exactly the same thing. The only time that Chinese martial artists were reliably uniformed seemed to be when they were lion dancing or otherwise part of a public festival. On the flip side, every single postcard of Japanese martial artists featured crisp white training uniforms, or matching rows of kendo gear.

Without a sufficient background in the social and cultural history of both countries, one might well misinterpret what was going on in these photographs, or extrapolate too much from them. For instance, one might look at these two sets of images and erroneously conclude that the uniforms tell a story about modernism, in either its economic, cultural or national sense. In that case the prominence of standardized uniforms within the Japanese martial arts might be taken as a sign of the country’s successfully modernization and the victory of nationalism over regional identity. Likewise, their absence in the Chinese case could indicate a certain “failure to launch.” Indeed, it seems likely that this was exactly the message that many Westerners absorbed when they encountered these images in the early and mid 20thcentury. But was it really the case?

Let us begin by considering developments in Japan. While many martial arts historians have written on the appearance of colored belts (first in judo, then in karate and other arts), I would like to instead turn our attention to the development of the ubiquitous training gi that they adorned. The samurai did not train in these garments, so where did they come from?

As is the case with so much else in the modern martial arts, they sprung from the fertile mind of Kano Jigoro. Lance Gatling, a student of Japanese martial arts history with an interest in the history of uniforms, notes that in the 19thcentury Kano drew his students from two vastly different backgrounds. Naturally these sociological cohorts dressed quite differently. Those coming from wealthy and socially elite households wore the latest fashions. His less privileged students, who often lived with him and acted as houseboys in exchange for tuition, lacked hygienic and functional training clothing of any kind. Calling on his background as an educator, it was clear to Kano that some sort of uniform was needed for both practical and symbolic reasons (Gatling, The Kano Chronicles).

Gatling notes that Kano adapted the hada juban, an inner-tunic worn underneath the kimono, for use as a training garment. This was done by commissioning examples made from heavier fabrics that could withstand judo’s jacketed throws. Later the garment was expanded to cover the knees and elbows to prevent abrasions or injuries on the rough training mats of the day. Simple belts were worn to keep the jacket in place. Of course Kano later introduced a simplified system of symbolically colored belts when his classes became large enough that he could not easily visually locate his senior students.

All of this set a pattern that still conditions much of the public’s imagination as to how a proper martial art should appear. For instance, when karate was introduced to mainland Japan from Okinawa, judo style uniforms were introduced to improve the arts’ public image and bolster its claims to social respectability. And while colored belts are in no way traditional to the Chinese martial arts, it seems that most kung fu schools today have some sort of colored sash system simply to placate the demands of consumers.

Kano’s many marital arts reforms did not come about in a vacuum. Japan was a rapidly modernizing and industrializing nation. He actively sought to create a corps of patriotic young men who could advance the Japanese cause at home or abroad, in military service or civil society. Thus, the creation of truly uniform training gear, recognizable in any dojo one might enter, had important symbolic meanings. This was an outward sign of the creation of an inwardly powerful and cohesive national consciousness. To wear a gi and participate in judo training was to experience Kano’s vision of the modern Japan nation on an embodied level.

This contrasts with the situation in China. Perhaps the most traditional form of training attire seen in that country’s many hand copied martial arts manuals (and a number of European postcards), was simply to strip to the waist, wrap one’s que around the head or neck, and get to work at a dusty or muddy outdoor “boxing ground.” Such attire was practical, yet it signaled little about the relationship between the martial arts and the community at large. In other cases Qing era boxers can be seen performing in markets wearing generic heavily padded jackets to ward off the cold. If Japan signaled its modernism and nationalism through its uniforms, one might conclude that China’s backward and politically fractured status also came out in its lack of standardized training attire. That is probably why later Republican groups, like the Jingwu Association, went to such great lengths to create signature uniforms of their own (in their case the white buttoned jacket with the Jingwu logo).

While an attractive narrative, I think that this risks missing much of what was actually happening. The danger is that we have focused only on a single axis when in fact uniforms represent a more complex field of meaning. For instance, Gatling notes that most early training gi were not purchased from a martial arts supplier as might be the case today. Rather they were made by Japanese housewives and mothers according to patterns that were distributed in either magazines or by schools. Indeed, it may be just as interesting to consider the ways in which huge numbers of Japanese women experienced Kano’s nationalism as they painstakingly hand sewed these uniforms for their sons and husbands, rather than engaging in training themselves. Thus we need to be careful that we do not equate vertically enforced uniformity with economic industrialization or a lack of individual artistic expression.

There is also the interesting question of who gets photographed. Most of the Japanese postcards in my collection were produced by Japanese photographers for sale to Japanese consumers. As such, they tended to focus on the sorts of progressive, middle class, scenes that Japanese consumers wanted to see. When modern scholars examine this ephemera we tend to see well stocked martial arts schools in reasonably urban areas. We forget that in the countryside most students toiling in their school’s dojo lacked gi’s and many practiced in regular physical education uniforms. Likewise, as more students were rushed into judo and kendo training as these disciplines were militarized in the run-up to WWII, it was increasingly common to find students simply putting their armor over their normal school uniforms. Gatling finds that while one might think that the rise in militarism would manifest itself in the spread of uniforms and the tightening of dress codes, in fact the opposite happened. In any case, this sort of nuance was unlikely to show up on commercially produced postcards.

Most postcards showing Chinese martial artists were produced by European photographers and were sold to Western audiences. They typically focused on more “rustic” street performances, poor soldiers or questionable bandits. All of these groups were relatively marginal and (with the exception of the soldiers) unlikely to wear any sort of uniform. Images of bare chested martial artists remained common throughout the 1920s. But this doesn’t mean that uniforms were absent within the Chinese martial arts.

The Republic period actually saw a proliferation of uniforms. The situation was different than in Japan as no single template emerged as the clear winner. Instead many things were happening at the same time. Most of these Chinese efforts were forward looking and modern in their sentiment. This could be seen in the Jingwu Association’s crisp white jackets, or the sportscoats, knickers and canvas belts that Ma Liang dressed his military exhibition teams in. Many reformers filled their manuals with photos of teachers and students who looked as though they were about to head out for a round of golf. In other cases the traditional robes of Confucian scholars were favored by more senior members of the community. I have often wondered whether relatively affluent Chinese martial artists during the 1920s-1930s insisted on working out in their street clothes in an effort to draw a conscious distinction between their understanding of community and the one advanced by the Japanese martial arts.

More practical were the working-class schools in cities like Guangzhou and Hong Kong. During the Republic period innumerable classes and lion dance societies began to adopt identical, mass-produced, t-shirts. Some of these were marked with the name of a school, while others were simply blank. Indeed, the practice of matching t-shirts being worn at a street festival has a long and distinguished history with the Chinese martial arts. In actual fact they may be just as “traditional” as karate’s signature uniform, both of which date roughly the same period during the interwar years. And both have proven to be remarkably stable over time. They succeed precisely because they signal different sets of values and understandings of the community.

Conclusion

Uniforms are inevitably symbolic representations of the communities that produced them. My students are excited to order a group of T-shirts not because of any practical need. Instead they are an expression of a new set of relationships, values and understanding of the self. Clothing speaks both to the individual and larger audiences, stabilizing and celebrating our collective achievements.

When reviewing the Martial Arts Studies literature I am often surprised that we have little to say on the question of material culture within the martial arts. We explore these fighting traditions as both embodied practices and media discourses. We look at their history and engage in conceptual debates. Yet little thought is given to the systematic examination of the uniforms, the training tools, the weapons and even the real estate that we all depend on.

When studying “primitive” societies Anthropologists took a keen interest in understanding and analyzing the various facets of material culture. They realized that these objects held both utilitarian and symbolic value. They were the physical manifestation of social and cultural values. Some of the insights that they suggest could not really be grasped through other modes of analysis.

I would like to propose that all of this also holds true for students of martial arts studies. Purchasing objects is one of the main modes of social activity that we see in an andvanced industrialized society, and that makes it doubly important to look carefully at the physical culture that is being consumed. I suggested a fairly simple framework to help us think more carefully about the varieties of uniforms in this article, and I am sure that there are other models that would have been just as helpful. Regardless of what theoretical lens you choose to adopt, the next time you are visiting a school and someone hands you a t-shirt, a uniform or a training weapon, think carefully about the full range of values that they are expressing. Our material culture often says more about our communities than we might care to admit.

oOo

If you enjoyed this reflection you might also want to read: Folklore in the Southern Chinese Martial Arts: A Means to Create Economic “Value” or to Construct Social “Values?”

oOo