Of Pens and Swords: Jin Yong’s Journey

The Loss of Heroes

The Chinese martial arts community has lost two giants. The death of Rey Chow (who was instrumental in jumpstarting Bruce Lee’s martial arts films) and Louis Cha (who wrote under the name Jin Yong) comes as a double blow. Granted, neither man is remembered primarily as a practitioner of the martial arts. Yet as story tellers they had a huge impact on the development of the shared web of signs, meanings and desires that would shape the development of the Chinese martial art community from roughly the 1950s until the present. As scholars we need to pay close attention to this cultural web as it is the software that structures the human experience. While not strictly determinative, none of us will strive to accomplish that which we cannot imagine.

Both of these figures are deserving of an essay. Yet at the moment I find myself drawn to reflect on Cha. His stature as a literary figure, and frequent forays into modern Chinese politics (both from the editorial page and his service on various governmental committees) are fascinating in their own right. Yet I will admit to having some ambivalence regarding the cultural impact of his novels. To put the question simply, I find myself wondering what Hong Kong’s martial culture would look like today had “Jin Yong” accepted a newspaper job in Taipie in 1947 rather than Hong Kong.

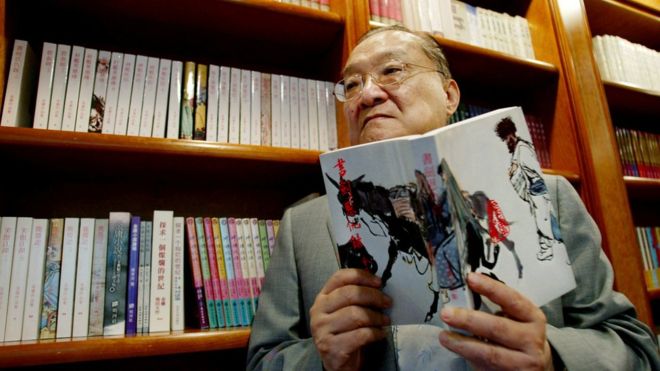

Simply asking such a question smacks of heresy. In many ways Loius Cha is synonymous with Hong Kong, his adopted home. He was the co-founder, and long-time editor, of the Ming Pao daily, a major publication. While Cha is still remembered for his blistering anti-Beijing editorials during the Cultural Revolution, he became the first (non-Communist) Hong Kong resident to meet with Deng Xioping as he sought to steer China on a more open path. And with over 100 million copies sold (not counting untold pirate editions), as well as derivative films, TV programs, radio dramas, comic books and video games too numerous to count, Cha’s novels are quite possibly Hong Kong’s most important cultural export within the Chinese cultural zone. Yet his impact on the Southern Chinese martial arts has been complex.

Perhaps the best way forward would be to review the contours of a remarkable career as we ask how it was that Cha, and a generation of immigrants like him, came to call Hong Kong home. This may suggest something about Cha’s impact on the development of Southern Chinese martial culture in the post-1949 era, as well as the continuing echoes and reverberations of his legacy today.

I should state for the record that I do not claim to be an expert in the analysis, or criticism, of Cha’s work, and have only read a few of his in novels in translation. I am sure that there are others who are better qualified to write an essay such as this. Nor is that admission an artifact of false modesty. The immense popularity of Cha’s novels have actually sparked the creation of an entire academic subfield (some of which even appears in English) dedicated to the study of his legacy. Still, his influence on the world of actual Chinese martial arts practitioners has been so great that I cannot leave his passing in silence. The complexity of his relationship with this community seems to stretch far beyond the platitudes that we encounter in his many newspaper obituaries.

Making a Hero

Like so many others, Cha first arrived in Hong Kong as a way station as he was headed somewhere else. He was born as Zha Liangyong in 1924 in Zhejiang province. His family had deep, multigenerational, scholarly credentials and it was only natural that Liang would also find a career in literature. But his pathway was far from straight. He exhibited his trademark penchant for fiery political rhetoric as a youth and was expelled from high school in 1941 after publicly denouncing the KMT’s government as “aristocratic”. Indeed, he would continue to identify himself as “anti-feudal” and “liberal” throughout his life.

After graduating from (a different) high school in 1943, Cha was accepted at the Department of Foreign Languages at the Central University of Chongqing. His initial plan was to become a foreign service officer or diplomat. However, he quickly dropped out of this program, and applied to study international law at Soochow University.

To help finance his studies Cha took a job in journalism with a major British owned paper. Fortuitously his company transferred him to the Hong Kong office in 1947. Things did not go well for all of Cha’s family who stayed behind after the Communist takeover in 1949. His father was arrested as a counterrevolutionary and executed in the early 1950s. Critics, like John Christopher Hamm (who has written one of the best English language studies of Cha’s work), note that his early novels are marked with a profound awareness of the plight of exile, alienation and loss. Like so many others who had come to Hong Kong for business or work, it quickly became apparent that there was no going home. Cha would be forced to build a new life in a largely Cantonese city under British colonial rule.

In the early 1950s Cha befriended Chen Wentong, a fellow journalist, who worked at the same paper. He encouraged Cha’s interest in writing and in 1955 (writing under the pseudonym Jin Yong) he began to produce the first of the serialized wuxia novels that would make him famous. In English this story’s title is typically rendered The Book and the Sword.

In 1959 Cha and his high school classmate, Shen Baoxin, established the Ming Pao daily newspaper with Cha serving as editor. The small paper started off as a home for “Jin Yong’s” increasingly popular novels, but it has since grown to be on the largest Chinese daily papers. In its first two decades Cha was responsible for writing not just the serialized novels but also the daily editorials and many small features. It is reported that at times he was publishing more than 10,000 characters a day.

In total Cha produced 14 novels and a single short story under the Jin Yong pseudonym. Then, in 1972, he retired and announced that he would concentrate on consolidating and editing his already extensive literary legacy. This was a complex undertaking as these novels had first appeared as serialized newspaper columns, which operated under their own set of literary conventions. In 1979 Cha released the first “complete and definitive” set of novels, many of which had been streamlined or slightly reworked in the editorial process.

The 1970s-1990s were a period of increased political activity in Cha’s life. He had always maintained an interest in politics (often understood through a more traditional Chinese cultural lens focusing on “the national interest”). Initially this led Cha to make many enemies on the left when he forcefully denounced the Cultural Revolution. Still, his reputation as someone capable of bringing together complex competing perspectives led to an invitation to meet with Deng Xiaoping and his subsequent appointment to the committee drafting Hong Kong’s Basic Law. Cha resigned that position in 1989 in protest over the Tiananmen Square Incident. Yet in 1996 he was once again working on the important Preparatory Committee, prior to the 1997 handover.

Not content to rest on his literary or political laurels, Cha pursued his lifelong fascination with Chinese history by pursuing a Doctorate in Oriental Studies at Cambridge University. His degree was awarded in 2010 when he deposited his dissertation focusing on imperial succession in the early Tang dynasty. Cha remained an important public figure throughout his life and his works have remained popular. A highly publicized English language version of his Condor Heroes series released its first installment in 2018. Cha died on October 30th2018, at 94, after a long period of illness.

Contextualizing a Life

John Christopher Hamm has argued that it is impossible to understand Jin Yong’s meaning or social significance without thinking very carefully about the environment that this literary phenomenon emerged in. Hong Kong’s newspapers were already well acquainted with the notion of serialized martial arts novels well before Cha’s arrival in the city. Indeed, the region had a rich, well-established, tradition of Kung Fu novels stretching back through the 19th century. Many of these were firmly rooted in Cantonese colloquialisms and local heroic figures. While one must be careful not to draw what were always shifting social borders too strictly, these stories typically appealed to the transient workers and merchants who came to Hong Kong to do business before returning (either at the end of a season or a career) to some other location in the Pearl River delta.

With the national upheavals of the late 1930s and 1940s, the city’s complexion began to change quite rapidly. Increasing numbers of displaced persons made their way to Hong Kong in an effort to escape the turmoil elsewhere in China. Since these Northern immigrants had the means to travel, they were often better off financially and more educated than much of the local population. Following the 1949 liberation of China by the Communist Party, they streamed in, effectively overwhelming the Guangdong culture that had dominated Hong Kong since its inceptions. It is interesting to note, parenthetically, that Ip Man and Louis Cha arrived in the city within a year and a half of each other, though they represented different cultural currents.

Like Cha these individuals slowly came to the realization that the 1949 crisis was not a limited event like the others that had marked China’s tumultuous 20thcentury. Rather than a temporary haven, Hong Kong had become their home for the imaginable future. Cultural clashes were common. Local Cantonese residents referred to these newcomers as “outlanders.” For their part the Northern refugees tended to see Hong Kong as a cultural wasteland. Cantonese culture was dismissed as backwards and new radio stations, theater groups and even newspapers quickly sprang up to cater to these northern “outlanders” who brought their own ideas about what modern Chinese life should be.

The Ming Pao daily was one of these institutions. And as Hamm notes, Jin Yong’s novels were a clear departure from the local kung fu tales that had previously dominated Hong Kong story telling. Acutely self-aware, his stories focused not on local heroes, but epic tales of contests for control of the Central Plains during periods of foreign occupation. When the heroes suffered their inevitable defeats, they retreated to the fringes of the empires and went into exile, just as Jin Yong’s readers had.

This is not to say that Jin Yong’s work didn’t have immense appeal, or that it was incapable of reaching a cross-over audience. As so many writers have recently noted, his novels have proved to be culturally enduring precisely because they speak to individuals across the geographic, ideological and economic lines that have traditionally divided the Chinese cultural area. They have managed to do so in large part by advancing an appealing, nuanced, vision of Chinese nationalism. Self-determination and cultural identity seem to rest at the heart of Cha’s understanding of patriotism. And in his later works he goes to lengths to praise China’s many ethnic minorities (particularly the ones that have contributed to its martial arts traditions) advancing a more open and liberal vision of what Chinese nationalism might be.

All of this is combined with a reverence for traditional Confucian values, particularly when they order the relationship between teachers and students, family members or leaders and followers. Yet the feudal past, in which all of his stories are set, is not accepted uncritically. Cha remained deeply suspicious of the feudal and aristocratic, and so his characters can be seen to wrestle with, and critically examine, practices that no longer work in the “modern” world of the 14thor 15thcenturies.

A lack of Cantonese colloquialisms notwithstanding, these themes were likely to have a broad appeal within Hong Kong society. Cha made sophisticated discussions about identity, belonging and the nation available to those with a variety of educational and cultural backgrounds. Yet these stories always originated from a specific place, or point of view. Nor can one help but wonder what other vision of martial arts culture they displaced, or pushed to the margins, as Jin Yong attained a sort of hegemonic dominance within the Wuxia genre. In my own research I frequently run across accounts of martial arts students in the 1960s and 1970s who, while enthusiastic to learn the southern martial arts, carried with them different visions about the values or identities that motivated these systems. Generational conflict over such matters is not unique to this case. Though as I read one testimonial after another as to how critical Cha was to defining the world view of a generation of Southern martial artists, I cannot help but wonder what he displaced, and to what degree he helped to shape the disjointed expectations of the period. Indeed, in my own account of Wing Chun’s history during the post-war era, Jing Yong’s novels are more likely to play the role of “loyal opposition” than protagonist.

The Journey North

The burgeoning hostility of local Hong Kong residents towards Northern visitors or residents is nothing new. It is easy to find recent newspaper articles and editorials referring to Northerners as “locusts” who sweep in to consume not just cheap goods, but increasingly the best real estate and jobs, pushing long-time residents ever further from the center. In the wake of his death some individuals openly wondered whether a figure like Cha could succeed today given the open hostility to immigrants. The great irony, of course, is that the majority of Hong Kong’s “legitimate” residents today were once northern transplants themselves, and Cha’s stories helped their parents to negotiate an environment that was not always friendly, familiar or welcoming.

By becoming the quintessential Hong Kong storyteller (a lack of Cantonese roots notwithstanding) Cha is once again acting as a cultural bridge. Amidst all of the anxiety about the death of the Hong Kong film industry, and the future of the Southern Chinese martial arts (which are being priced out of the city by skyrocketing rents), it is easy to forget that in some ways the Cantonese martial arts heroes are now more popular than ever throughout the PRC. Ip Man has become a household figure (and his art has exploded in popularity) not just because of his association with Bruce Lee. Rather, Wilson Ip’s 2008 film and its many successors have been key in spreading this bit of Southern culture throughout the mainland.

It has been noted (by myself and others) that the vision of Ip Man that these films conjure does not bear a close resemblance to the real life (and rather well documented) figure. In the place of the undeniably mercurial and modernist Ip Man, what do these films present? A figure that in many ways splits the difference between the traditional Kung Fu genre and one of Cha’s stories. Yes, the action is still gritty and “realistic” with minimal wire work. But we now have a hero who exemplifies martial virtue, who demonstrates Confucian values in his relationships, who is a patriot who fights for China, and in defeat he retreats in exile to the edge of the empire. Does that sound familiar?

The flavor of these films is undeniably influenced by the Hong Kong tradition. Yet the mold that shapes the stories bears an uncanny resemblance to the ideal hero (a patriot who endures rather than wins) as laid out in Cha’s many novels. Where as Ip Man and Louis Cha had once existed as contemporary historical figures, whose lives ran on parallel tracks, their legacies now interact in complex ways. Rather than simply displacing the Pearl River Delta’s traditional Kung Fu narrative, Cha seems to have provided a pattern by which its heroes can travel North, testing their own fortunes in the Central Plains.

oOo

If you enjoyed this essay you might also want to read: Lives of Chinese Martial Artists (14): Ark Yuey Wong—Envisioning the Future of the Chinese Martial Arts

oOo