Research Note: A Visit with the Jingwu Association in 1928

At the moment I am working on a guest editorial project examining Afro-Caribbean and New World martial arts. It will pose a number of interesting questions and I hope to discuss some of these practices in greater depth. Unfortunately, the issues’ deadlines have turned out to be a bit tighter that we first thought, and it is monopolizing quite a bit of my time for the next few days.

Nevertheless, I recently came across a fascinating newspaper article that I wanted to share with the readers of Kung Fu Tea. My discussion of this piece must be brief, but the article’s contents are interesting enough that it can stand on its own.

Still, just a bit of framing may be helpful. Almost every national-level discussion of the Jingwu Association within the historical literature on the Chinese martial arts ends rather abruptly with the bankruptcy of its founding members in 1924. Authors like Morris and Kennedy note, quite correctly, that the organization ceased to play a central role in the promotion of the Chinese martial arts at that point. The Jingwu brand is often assumed to have been broken and, in any case, the stage has already been set for the emergence of the Guoshu movement with the completion of the KMT’s Northern Campaign.

Again, this is all correct so far as it goes. Yet it also seems that most readers go on to assume that Jingwu simply vanished after this point and ceased to be any sort of force within the Chinese martial arts. That was most certainly not the case. To say that a group no longer (and almost single handedly) set the agenda for the reform of the Chinese martial arts is not the same as saying it ceased to play any role in that struggle.

While Jingwu’s founders and national structure took a punishing financial hit in 1924, many of its individual branches continued normal operations, and even made headlines with important events, right up until the eve of WWII. In The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts, Jon Nielson and I provide an extensive discussion of the later history of the Jingwu Association in both Foshan and Guangzhou, two cities where it continued to have a major impact on the martial landscape. Andrew Morris has also noted that the group continued to exhibit quite a bit of social clout in various South East Asian communities up until the present time.

The following article, first published in The China Press in August of 1928, reminds us that Jingwu also continued to function as an important force in Shanghai. Indeed, a month before the Central Guoshu Institute’s now famous first national martial arts exhibition, the Jingwu Association was commemorating an anniversary of its own in front of an assembled crowd of over a thousand guests.

While press accounts of Jingwu demonstrations are not uncommon, this one is interesting as it reviews the sorts of political, social and cultural presentations that framed the martial arts exhibits in great detail. It seems that even in 1928 the Association was presenting a face designed to appeal to an educated and upwardly mobile middle class. This particular account is also interesting in that it lays out so many names for future investigation.

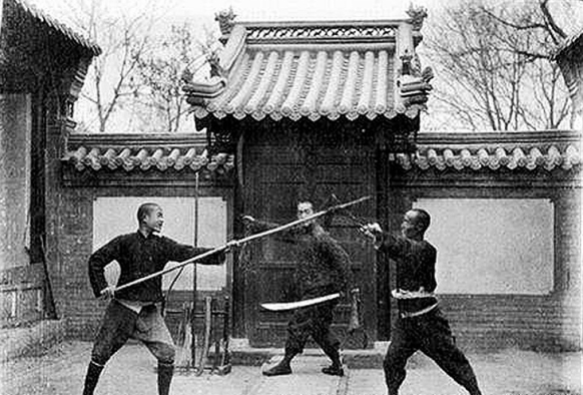

Beyond that, I was struck by the unnamed reporter’s frequent use of the term “sword playing” in an apparent description of taolu. Many press accounts from the period refer to these solo-forms simply as “sword dancing” or “gymnastics.” However, the English language vocabulary used to describe Chinese martial arts practice was far from standardized in the 1920s, and tends to shift from one newspaper to the next. We can now add “sword playing” to the ever-growing list of key words to be used when conducting electronic searches.

Still, for all of the pretense at educational theory and middle-class respectability, it is important to note that The China Press continued report all of this as an athletic event, rather than as cultural or political gathering. In fact, it was placed directly besides an item of boxing news titled “British Lightweight, Jack Berg, Defeated by ‘Fargo Express.’” Even after its ostensible fall, the Jingwu Association was still being invoked in the local press as a uniquely Chinese answer to Western athletics and physical culture.

Physical Exhibition Held Last Night by Chinese Athletes

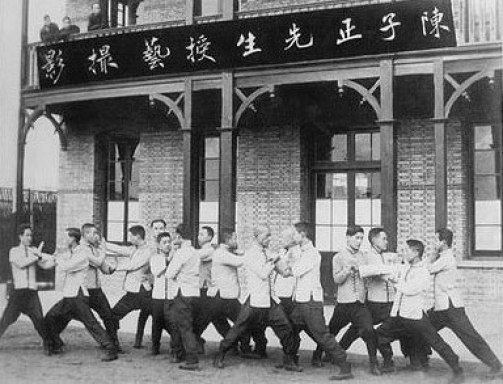

Speeches, Chinese gymnastics consisting of wrestling, boxing, fencing, sword playing, dances and Chinese music were featured [in] the 33rd physical exhibition of the Chin Woo Athletic Association which was successfully held last night at the Central Hall, North Szechuen, with more than a thousand guests in attendance. The Association was established 19 years ago, and is one of the oldest athletic associations in existence, whose main object is to promote the art of Chinese boxing. The exhibition is arranged to be held monthly and last nights was the most brilliant carried out.

The program began with the reading of the monthly report of the Association by Dr. Jackson Cheng, the Chairman of the Association, and was followed with a short speech by Mr. C. N. Shen, who is famous in educational circles. His speech mainly deals with the question of how to promote education in China, the service of the Association to the public in [the] athletic world being greatly praised and urged. After a concert which was appreciated by all, gymnastic exercises consisting of boxing, fencing, [and] sword playing were exhibited.

Mr. Woo Chien-chuan, of boxing fame displayed a classic in boxing to the delight of the audience. A number of guests, who are experts in the art, were also invited to play Mr. K. C. Chee’s sword-playing, Mr. V. M. Chen’s boxing, and Mr. Yeh’s sword-playing, [and] a duel were most favorably appreciated by the audience.

Boxing and sword-playing were also exhibited by girl members whose efficiency in the art surpasses all present.

The program was then concluded with a musical program.

“Physical Exhibition Held Last Night by Chinese Athletes.” The China Press. Aug. 26, 1928. p. A2