–

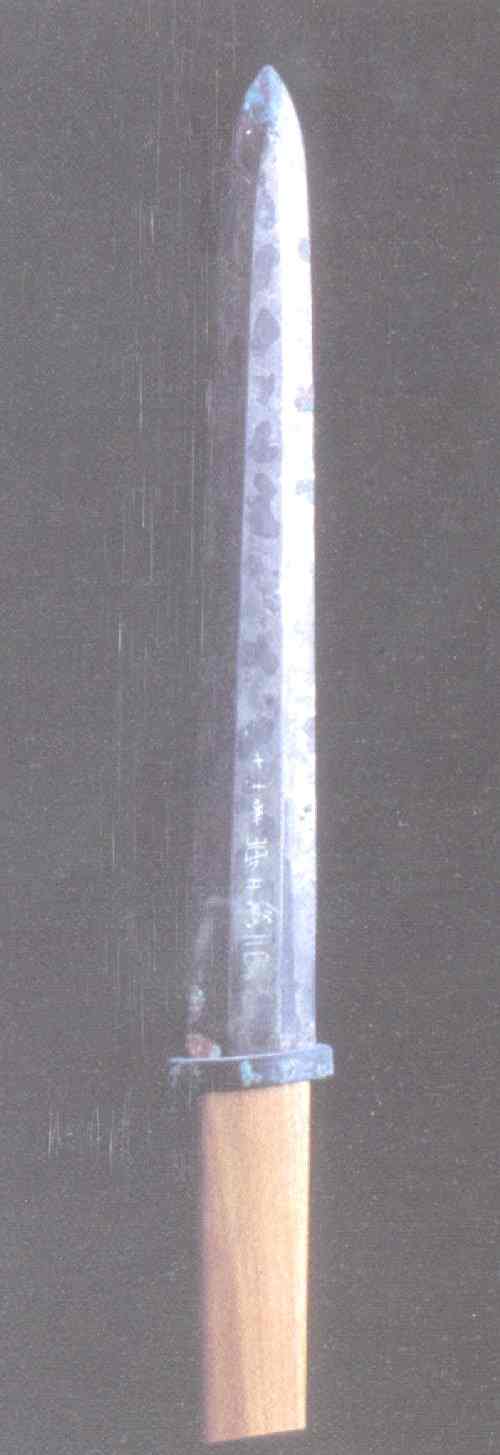

太極拳使用法

METHODS OF APPLYING TAIJI BOXING

楊澄甫

by Yang Chengfu

[and 董英傑 Dong Yingjie]

[published by 神州國光社發行 Society for Chinese National Glory, Jan, 1931]

[translation by Paul Brennan, Nov, 2011]

–

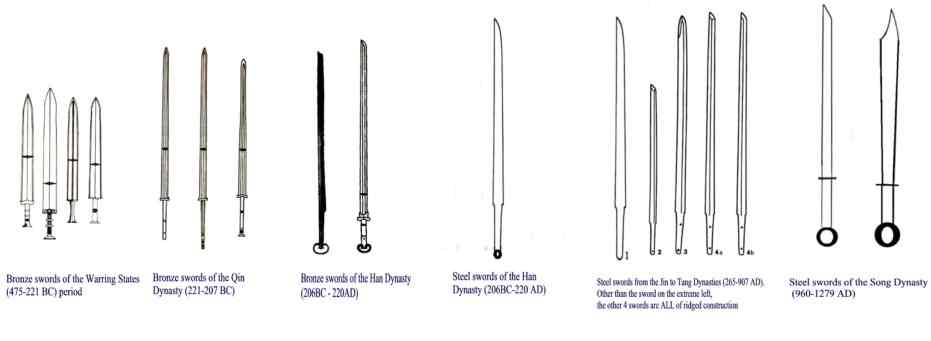

武當嫡派

“Descended from Wudang”

–

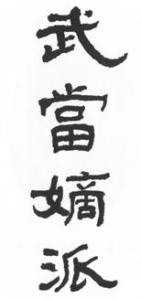

楊健侯先師遺像

Photograph of the late Yang Jianhou

–

著者楊澄甫

The author, Yang Chengfu

–

田兆麟

Tian Zhaolin

–

武滙川

Wu Huichuan

–

董英傑

Dong Yingjie

–

王旭東

Wang Xudong

–

閆仲魁

Yan Zhongkui

–

李得芳

Li Defang

–

楊振銘

Yang Zhenming

–

姜廷選

Jiang Tingxuan

–

褚桂亭

Chu Guiting

–

李椿年

Li Chunnian

–

徐岱山

Xu Daishan

–

郭蔭棠

Guo Yintang

–

張慶麟

Zhang Qinglin

–

楊開儒

Yang Kairu

–

張三峯先師傳拳譜

ZHANG SANFENG BOXING LINEAGE

三峯師傳山右王宗岳

Zhang Sanfeng imparted to Wang Zongyue of Shanxi.

河南─後又傳陳家溝陳長興 楊露禪 李百魁 及子姪輩

Wang taught in Henan province to Chen Changxing of Chen Family Village, who in turn taught Yang Luchan, Li Baikui, and his sons and nephews.

張松溪 王來咸 為浙江東支派惜已失傳

Wang also taught in Zhejiang province to Zhang Songxi and Wang Laixian, but this branch is extinct.

福魁露禪師傳

Yang Fukui (Luchan) taught:

鳳侯傳子……兆林字振遠

– Fenghou, who taught his son, Zhaolin (called Zhenyuan),

班侯傳……外姓數人

– Banhou, who taught many people outside his family,

健侯傳子……兆淸字澄甫

– Jianhou, who taught his son, Zhaoqing (called Chengfu),

傳……外姓數人

– and many people outside his family.

澄甫老師傳

Students of Yang Chengfu:

楊兆鵬

Yang Zhaopeng

武振海字滙川

Wu Zhenhai (called Huichuan) [photo above]

田兆麟

Tian Zhaolin [photo above]

董英傑

Dong Yingjie [photo above]

王旭東

Wang Xudong [photo above]

閻月川

Yan Yuechuan

牛鏡軒

Niu Jingxuan

田作林

Tian Zuolin

徐岱山

Xu Daishan [photo above]

褚桂亭

Chu Guiting [photo above]

劉論山

Liu Lunshan

李得芳

Li Defang [photo above]

李春年

Li Chunnian [photo above]

陳微明

Chen Weiming

楊鳳岐

Yang Fengqi

張欽霖

Zhang Qinlin

鄭佐平

Zheng Zuoping

王其和

Wang Qihe

崔立志

Cui Lizhi

王鏡淸

Wang Jingqing

楊振聲

Yang Zhensheng

楊振銘

Yang Zhenming [photo above]

楊振基

Yang Zhenji

姜廷選

Jiang Tingxuan [photo above]

陳光愷

Chen Guangkai

張慶麟

Zhang Qinglin [photo above]

王保還

Wang Baohuan

形玉臣

Xing Yuchen

劉盡臣

Liu Jinchen

匡克明

Kuang Keming

楊鴻志

Yang Hongzhi

師孫楊開儒

(having learned first from one of Yang’s students [Tian Zhaolin]) Yang Kairu [photo above]

于化行

Yu Huaxing

女士濮玉與第二人

(woman) Pu Yu (along with the second woman below)

女士滕南璇

(woman) Teng Nanxuan

奚誠甫

Xi Chengfu

朱紉芝

Zhu Renzhi

郭陰棠

Guo Yintang [photo above]

師孫吳萬琳

(having learned first from one of Yang’s students) Wu Wanlin

師孫孫件英

(having learned first from one of Yang’s students) Sun Jianying

李萬程

Li Wancheng

張種交

Zhang Zhongjiao

[Odd that Yan Zhongkui is absent from this list even though he is one of the photographed.]

田兆麟傳─

Students of Tian Zhaolin:

葉大密

Ye Dami

張景淇

Zhang Jingqi

陳一虎

Chen Yihu

施承志

Shi Chengzhi

陳志進

Chen Zhijin

鄭佐平

Zheng Zuoping [also in Yang Chengfu’s list]

楊開儒

Yang Kairu [also in Yang Chengfu’s list]

錢西樵

Qian Xiqiao

陳志遠

Chen Zhiyuan

張强

Zhang Qiang

何瑞明

He Ruiming

沈爾喬

Shen Erqiao

何士鑣

He Shibiao

周學淵

Zhou Xueyuan

周學芬

Zhou Xuefen

張寶鳳

Zhang Baofeng

崇壽永

Chong Shouyong

董英傑傳─

Students of Dong Yingjie:

劉同祿

Liu Tonglu

連忠恕

Lian Zhongshu

張忻

Zhang Xin

陳寧

Chen Ning

顏福廷

Yan Futing

郝奇

Hao Qi

宗之鴻

Zong Zhihong

宗毛三

Zong Maosan

孫僧齡

Sun Sengling

–

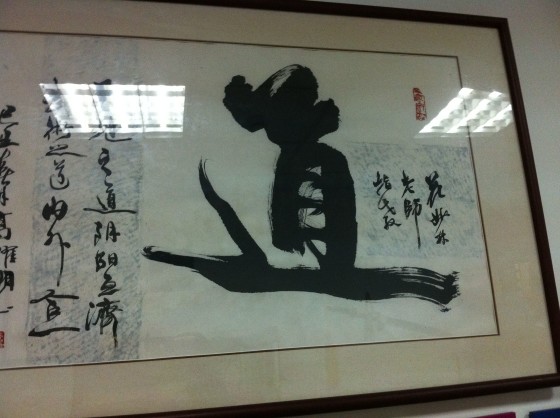

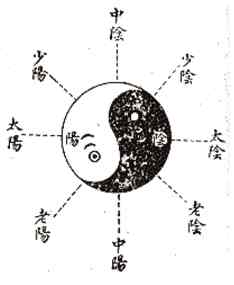

太極圖

DIAGRAM OF THE GRAND POLARITY [TAI JI]

陰 陽

陰 陽

THE PASSIVE [YIN] / THE ACTIVE [YANG]

太極圖之義陰陽相生剛柔相濟千變萬化太極拳即由此而出也推手即太極之圖形

The idea within the Taiji diagram is that passive and active generate each other, hardness and softness assist each other, and the polarities endless transform into each other. Taiji Boxing comes from this, and the pushing hands is the manifestation of this symbol.

–

太極拳原序

ON THE ORIGIN OF TAIJI BOXING

太極拳傳自張眞人,眞人,遼東懿州人,道號三峯,生宋末,身高七尺,鶴骨松姿,面如古月,慈眉善目,修髯如戟,頂作一髻寒暑唯一箬笠,手持佛塵,日行千里,洪武初,至蜀太和山修煉結庵玉虛宮,經書一覽成誦,洪武二十七年,又入湖北武當山,與鄕人論經書談說不倦,一日在屋誦經,有喜雀在院,其鳴如箏,眞人由窗視之,雀在柏樹,如鷹下觀,地上有一長蛇蟠結,仰視,二物相爭,雀鳴聲飛下展翅扇打,長蛇搖首微閃,躱過雀翅,雀自下隨飛樹上,少時性燥,又飛下翅打,長蛇又蜿蜒輕身閃過,仍作盤形,如是多次並未打着,後眞人出,雀飛蛇走,眞人由此而悟,蟠如太極,以柔克剛之理,由按太極變化而組成太極拳,養精氣神,動靜消長,通於易理,故傳之久遠,而功效愈著,北京白雲觀現存有眞人聖像可供瞻仰云。

Taiji Boxing was passed down from the Daoist saint, Zhang. He was from Yizhou in Liaodong. The monastic name he was given was Sanfeng. He was born during the end of the Song Dynasty [ending in 1279]. Standing seven feet tall, he had a crane’s build and a pine’s bearing. His face was like the aged moon, with kindness in his eyes and brows. His beard was as long as a halberd and his hair was in a bun atop his head. Regardless of winter or summer he wore the same wide hat of bamboo. He held a Buddhist duster and walked immense distances in a single day.

At the beginning of Emperor Hongwu’s reign [1368], Zhang went to Mt. Grand Harmony in Sichuan to practice asceticism, joining the Temple of Jade Emptiness monastery, and recited the scriptures after just one reading. In the twenty-seventh year of Hongwu’s reign [1394], Zhang traveled again, going to Mt. Wudang in Hubei, and he tirelessly conversed with the villagers about the scriptures.

One day, while reciting passages in his room, an excited sparrow appeared in the courtyard. Because of its zither-like chirping, the saint looked out his window to watch it. The sparrow was in a cypress tree, gazing down eagle-eyed, while on the ground there was a snake coiling and weaving, looking up at the sparrow. The two animals were fighting. The sparrow cried out and flew down, spreading its wings to give flapping strikes. The snake waved its head to slightly dodge, avoiding the sparrow’s wings. The sparrow returned to the tree to express its annoyance for a while then flew down to try again. The snake again wriggled its nimble body to evade, remaining in its coiled shape. It went on like this many times without a strike. Then Zhang came out and the sparrow flew away and the snake slithered off.

The saint was illumined by this incident. The snake’s coiling was like the taiji symbol and used the principle of softness overcoming hardness. From the taiji’s transformations was devised Taiji Boxing. It cultivates essence, energy, and spirit. Movement and stillness wax and wane as in the theory of the Book of Changes. This is the way it comes down to us from long ago and its effectiveness is increasingly proven. In Beijing’s White Cloud Temple there is still an image of the saint which can be reverenced.

–

楊露禪先師軼事

AN ANECDOTE ABOUT YANG LUCHAN

初師在京師聲聞遐邇,俠來訪者踵接,一日靜坐間,忽有僧來,師自迎出階,見僧貌偉壯,身高六尺許,拱揖道慕意,師亟遜答,僧鶻起出拳直撲師,師略含胸,以右掌抵拳頂拍之,僧如受電擊,跌出屛後猶作拳擊狀,久之乃歛容稱謝曰,僧鹵莽,師仍邀與談,審其名為淸德僧,固少林健壯者也,僧縷縷問,頃出不意猶不得逞何也,師曰,是謂刻刻留心也,曰頃出何其疾也,曰,是謂發勁如放箭也,曰僧雲遊幾省,未有如師者,堅叩太極輕靈之奧,師不答,見有飛燕入簾,低繞近身,即起手速抄之,顧謂僧曰,此鳥馴就人,聊與為戲何如,輒承以右掌而左手撫之,旋縱使去,燕振翼擬起,師微將掌忽隱忽現,燕不能飛去,蓋無論何種雀鳥,必先足蹬勁才能飛,燕足無着力處,遞撲伏,則又撫之使去,復不得起,如是者三,僧大訝曰技何神也,師笑曰,奚足言神,太極行功稍久,通體輕靈一羽不能加,蠅蟲不能落,畧如是狀耳,僧拜服,留談三日乃去。

When Yang was in Beijing, he was heard of everywhere. Fighters crowded upon each other to visit him. One day, in the midst of seated meditation, suddenly a Buddhist monk arrived. Yang personally went to receive him at the stairs. He saw that the monk’s appearance was imposing and strong and that his height was about six feet. When the monk saluted and spoke his esteem, Yang immediately became humble in response. Then the monk suddenly launched out a punch. Yang slightly hollowed his chest and used his right palm to slap the top of the incoming fist. The monk seemed to receive an electric shock and fell away behind a screen while still in the posture of punching. After a while, with a sober expression on his face, he thanked Yang and said, “That was very rude of me.” Yang invited him in anyway and they chatted. He found out that he was called the Pure Integrity Monk and that he was indeed a tough exponent of Shaolin. The monk asked him questions one after another, such as:

“Just now when I attacked you, I took you by surprise, so why was I still unable to succeed?”

Yang said, “This is called ‘paying attention at every moment’.”

“When I attacked you, how is it that you were you so fast?”

Yang said, “This is called ‘issuing power like loosing an arrow’.”

“I have traveled to many provinces but have met no one the likes of you. I sincerely ask the secret to Taiji’s nimbleness and quickness.”

Yang said nothing, seeing a swallow fly through his curtain and then lower in an arc nearby him. He promptly lifted his hand and scooped it up, then looked over at the monk and said, “This bird is tame and unafraid of people, so why not have some fun with it?”

The way he did this was to put it in his right palm while petting it with his left, then took away his left hand to let it fly away, and the swallow flapped its wings and tried to take off, but he was slightly moving his palm to be one moment there and the next moment not, and so the swallow could not fly away. Every kind of bird must first push with its feet to be able to get into the air, but the swallow had nothing to push against. It gave up, so Yang returned to petting it, then gave it another chance, but again it could not get into the air.

After a third round, the monk was astounded and said, “This skill is magical.”

Yang smiled and said, “What’s so magical about it? Practice Taiji for a long time and the whole body will become so nimble and quick that a feather cannot be added and a fly cannot land. That basically sums it up.”

The monk bowed in admiration and continued to converse with Yang for three more days before finally leaving.

–

序

PREFACE [BY DONG YINGJIE]

余幼讀書時,性好武,余祖有老友劉瀛州少林壯者,北方名素著,余求學,劉師曰我年近七十,無能為也,如願學,有廣平楊姓得武當秘傳,惜我年老知之晚矣,僅知皮毛,與介紹楊傳,拜師求學焉,研究十有五年,惜余最魯,略知大槪,諸師兄師弟皆出我上,余今從師歷方從學,遊歷保定,北平,天津,上海,南京,蘇杭,江西,山東,曾見廣東,雲南,陝西,山西,河南,安徽,湖北,湖南,各省武術大家,各處山川古蹟,觀之不已,各省內外武術大家,令人學之不盡,勸同志苦心研究無懈志也,今余始知武術深有奧妙,正在從學研究中,今國家提倡武術,幸吾師又作是書,任縣董英傑喜而為之序。

When I was young and in school, I was interested in martial arts. My grandfather had an old friend, Liu Yingzhou, who was good at Shaolin and was in the north and well known. I went to learn from him, but he told me: “As I am almost seventy, I am not capable. If you want to learn, the Yang family in Guangping have obtained the secret Wudang transmission. Unfortunately in my age I have known it too late and I only understand it superficially, but I recommend the Yang transmission. Go seek to learn from them. I studied for fifteen years, but alas, I am really stupid and I only know the general idea. All of my fellow students, whether elders or juniors, did better than me.”

By now I have learned from teachers everywhere. I traveled to Baoding, Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Nanjing, Suzhou & Hangzhou, Jiangxi, Shandong, visiting Guangdong, Yunnan, Shaanxi & Shanxi, Hebei, Anhui, Hubei & Hunan, to martial arts masters of each province, every place in the land where there are ancient traces of it, observing ceaselessly the masters of internal and external martial arts. It has made me learn without end. I urge my fellow practitioners to work hard and study without slackening in their devotion. Nowadays I am beginning to understand the deeper subtleties of martial arts, directly due to learning and studying. Now the nation is encouraging martial arts and it is a wonderful thing that my teacher has also produced this book.

– written with delight by Dong Yingjie of Ren county

勸諸同志莫懈心

日月穿梭貴如金

朝夕時時要習練

功夫無息得玄眞

I urge all my fellow practitioners not to be lazy.

Work at it day after day, month after month, for it is as valuable as gold.

From morning to eve you should constantly practice.

Work at it unceasingly and what you will obtain will be as precious as jade.

–

序

PREFACE [BY TIAN ZHAOLIN]

技術者,為我國國粹之至寶也,惜多年不振,幾于失傳,幸今國家提倡武術為必要,余踴躍為之序,今楊師南來,與同志互相研究,發展普及起見,余雀躍之至,因余為國民一份子,亦要加入提倡,惜才學最淺,總不免熱心耳,拳有外壯,內壯,余偏愛於內家太極,奥妙筆亦難言,尊師常談,輕則靈,靈則動,動則變,變則化,余苦功從學研究二十有年,不能得百分之一,雖然,余常懷有志竟成,每日在研究中也,田兆麟謹序。

These skills are the greatest treasure of our culture. It is a pity that for so many years they have not been encouraged and many of them have consequently been lost forever. Fortunately nowadays our nation is promoting martial arts as being indispensable, and so I enthusiastically write this preface. Yang Chengfu is now away visiting in the south so he and other practitioners can study with each other, and the growth and spread of these arts is beginning to be seen. I am overjoyed because I get to participate in this national undertaking and I would like to add my own encouragement. It is too bad I am no scholar, but at least I am certainly enthusiastic.

In boxing, there is an external strength and an internal strength. I am partial to the internal school’s Taiji, which has profound writings but is difficult to discuss. I revere this common saying of my teacher’s: “With lightness there is sensitivity, with sensitivity there is movement, with movement there is adaptation, and with adaptation there is transformation.” I have worked hard learning from him for twenty years but I have been unable to master even one percent of it. Although I firmly believe that with a will there is a way, and so I spend every day in the study of it.

– sincerely written by Tian Zhaolin

–

凡例

GENERAL REMARKS [Part 1]

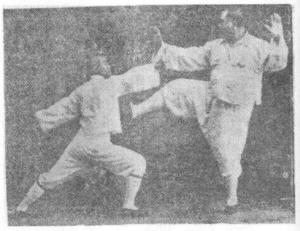

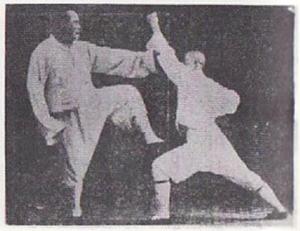

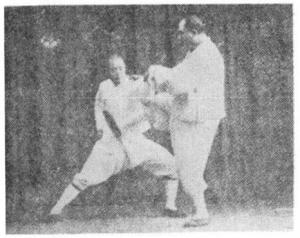

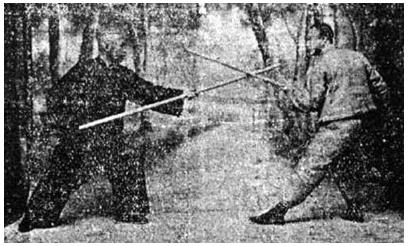

一本書專就已經練習太極拳而尚未明實用者特按名式說明並附圖以表出之

– This volume is geared toward those who already practice Taiji Boxing but do not yet understand its practical functions. Especially pay attention to the explanations for the main postures and the photos which demonstrate them.

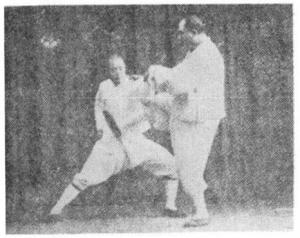

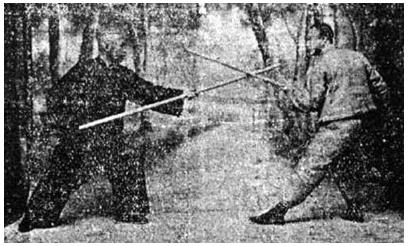

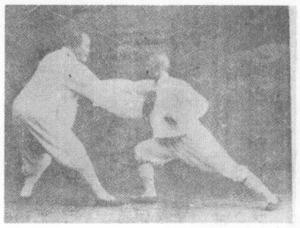

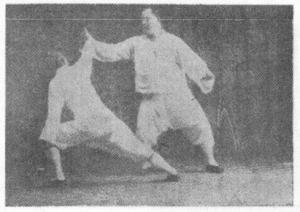

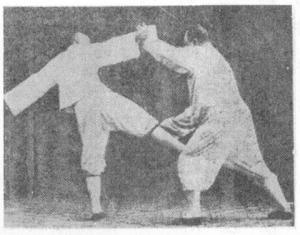

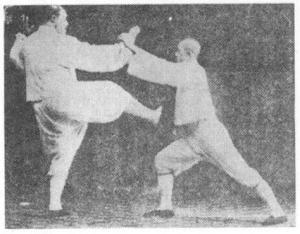

一本書下列太極拳應用交手圖式甲乙二人演練時宜就各圖姿勢循序彷行

– There is in this volume a scheme to the practical applications, meaning that when two people practice together, they should do them in sequence.

一本書逐段標明按各式銜接動作以至二人發手之際均用白話表明學者可詳細參閱自有路徑可尋

– Every posture is described step by step through the movements all the way to the point where the two people are expressing the techniques upon one another, which is always described in ordinary language, and students are thereby equipped with a detailed reference and have the means to seek the path.

一甲乙二人合手演習時可輕行緩進實地研習自有得法之處不可躁進率爾逞强以致發生危險彼此反生惡感

– When two people practice together, they can treat it as something frivolous and progress slowly or they can study seriously. When you have a moment of advantage, you must not be anxious to advance or eager to show off. If you do, it will become dangerous for you as you will both oppose each other with anger.

一本書均就單行法解釋之遇有手術相同者從畧

– Individual techniques will be explained only once and repetitions omitted.

一本書附圖應用動作各式方向均以上下前後左右两側表示之不拘定於東西南北以其臨時動作無有一定之方位故也

– The photos exhibit in various directions – up, down, forward, back, left right. Their orientations of north, south, east, west are kept constant because the direction of the movements is not.

一本書各姿勢應用法式僅就一二手術編列說明之其臨時動作變化之妙在好學者深思遠造久練功純自能得其要領非空言所能及也

– In the application models for each posture, only one or two techniques have been compiled. When their situations are explained, the subtlety lies in the movement transitions. To achieve it depends on the good student pondering deeply. With ardent practice over a long period you will naturally obtain the essentials. These are not empty words. It is a realizable goal.

一本書編製各式均用白話挨次淺顯說明以便閱者一目了解

– Each posture is explained in ordinary language so as to make it easy to understand.

一本書編成其中字句難免有遺漏錯誤之處望閱者諒之

– Inevitably there are omissions and errors in the text. When you come across them, forgive.

一此書是楊老師所述拳理同志閱書千萬不要以文字挑之祗應注重拳理如以文法挑之恐有誤自己學拳之門徑願同志諒之

– This book is Yang Chengfu’s transmission of boxing theory. But fellow practitioners who read through it should by no means take the writing too seriously. You should only lay importance on the theory. If you are finicky about the writing, you will likely make mistakes in your own study of the boxing methods. And so I hope you all will pardon the writing.

太極拳本係武當內功拳,欲鍜練身體者可習太極拳,此係柔功,無論男女老幼皆相宜,小兒六歲以上,老者六十歲以外,皆能習學,身體虛弱者更可習學,數月之間漸覺强壯耳,十三勢初學期三個月學會,一年習熟,五年練好,日後愈練愈精,但非眞傳不可,太極拳不得眞傳不過身體畧壯耳,拳理十年終糊塗,焉能知精微奧妙知覺運用,若得眞傳如法練去,金剛羅漢體不難矣,不但體壯,自衛防身之能力庽焉,早晨練拳最相宜,飯後休息半時或一時方可運動,如體質弱者量力練之,不可過,練習一月之後飲食可加多,拳每早晚两次或三次均可,如夏天練拳正燥,千萬不可用凉水洗手,恐其悶火,如冬天練完速穿衣服恐其受凉,練完不可即就坐,可行走五分鐘,使血脈調和

– Taiji Boxing is fundamentally related to Wudang’s boxing of internal skill. If you want to refine the body, you can practice Taiji Boxing. This is a gentle skill and is suitable for all, regardless of man or woman, young or old. Whether under six or over sixty, all can learn. The weak can learn it and after several months gradually become stronger.

When beginning to learn the Thirteen Dynamics solo set, it takes about three months to become acquainted with it, about a year to become familiar with it, and about five years to become good at it. After that, the more your practice the more refined it will be. But without the authentic transmission, that will not be the case. Without the authentic transmission, the only result will be a slightly strengthened body. The boxing theory after ten years would still be confusing. How would you know its profound subtleties? If you obtain the authentic transmission, and if the method is trained, you will easily gain a powerful body. Not only will your body be strengthened, you will also have the ability to defend yourself.

Practice in the morning is the most appropriate. After a meal, rest for a half hour or an hour and then you can exercise. If your physique is weak, practice according to your capacity and do not overdo it. After training for a single month, your appetite will increase. It is adequate to do a set every morning and evening two or three times. When practicing in the peak of summer, never wash with cold water or you may spark a fever. In winter, put on clothes right away after finishing your practice to keep yourself from catching cold. After practicing, you must not sit down but should instead walk around for a few minutes to regulate the circulation.

如用功時須澄心息慮,心無所思,意無所感,專心練拳,太極對敵法甚妙,非不能用,蓋今同志只練皮毛不再學,不能求高師訪明友,勿說太極不能用,亦勿怪授者不授耳,此本係內功與道相合,初學每日可學一两式,不可粗率,初學略難,一月後拳式入門易學耳,每同志初學一两月覺拳甚好,再學三四個月後自覺不如從前,心中煩燥,如有此景像千萬不可懈志,正是進步耳,如今拳未進步,不能自知拳式壞的,人人必由此地位經過,先此警告耳,

– When training, you must calm your mind and consider your breath. Dispel your thoughts and let nothing distract your intent. Focus your mind on the practice. Taiji’s way of dealing with opponents is very subtle but is not useless. Today most people only train superficially and then quit, or are unable to find a skilled teacher or an enlightened colleague. Do not complain that Taiji cannot be applied nor blame your instructors for a lack of instruction. It is fundamentally related to internal skill and is consistent with Daoism. In the beginning you will be able to learn a couple of postures every day, but you must not be sloppy in what you learn and in haste to learn more. In the beginning it will be somewhat difficult, but after a month the postures will be easier to learn. All beginners after a month or two feel their boxing has improved a lot, then after three or four months will feel they are worse than they used to be and become frustrated. When you get to that point, you absolutely must not slacken, for it is a sign you are making progress. If you were not making progress, you would not be able to notice your postures are not good enough. Everyone has to go through this, so we give you forewarning.

–

露禪師原文

YANG LUCHAN’S [COMMENTARY TO A] PRIMARY TEXT

[Original text:]

一舉動周身俱要輕靈,尤須貫串,氣宜皷盪,神宜內歛,毋使有缺陷處,毋使有凸凹處,毋使有斷續處,其根在脚,發于腿,主宰于腰,形于手指,由脚而腿而腰,總須完整一氣,向前退後,乃能得機得勢,有不得機得勢處,身便散亂,其病必於腰腿求之,上下前後左右皆然,凡此皆是意,不在外面,有上即有下有前則有後,有左則有右,如意要向上,即寓下意,若將物掀起,而加以挫之力,斯其根自斷,乃攘之速,而無疑,虛實宜分淸楚,一處有一處虛實,處處總此一虛實,周身節節貫串毋令絲毫間斷耳

Once there is any movement, the entire body should be nimble and alert. There especially needs to be connection from movement to movement. The energy should be roused and the spirit should be collected within. Do not allow there to be cracks or gaps anywhere, pits or protrusions anywhere, breaks in the flow anywhere. Starting from the foot, issue through the leg, directing it at the waist, and expressing it at the fingers. From foot through leg through waist, it must be a fully continuous process, and whether advancing or retreating, you will then catch the opportunity and gain the upper hand. If you miss and your body easily falls into disorder, the problem must be in the waist and legs, so look for it there. This is always so, regardless of the direction of the movement, be it up, down, front, back, left, right. And in all of these cases, the problem is a matter of your intent and does not lie outside of you. With an upward comes a downward, with a forward comes a backward, and with a left comes a right. If your intention wants to go upward, then harbor a downward intention, like when you reach down to lift up an object. You thereby add a setback to the opponent’s own intention, thus he cuts his own root and is defeated quickly and certainly. Empty and full must be distinguished clearly. In each part there is a part that is empty and a part that is full. Everywhere it is always like this, an emptiness and a fullness. Throughout the body, as the movement goes from one section to another there is connection. Do not allow the slightest break in the connection.

長拳者如長江大海,滔滔不絕也,十三勢者掤捋擠按採挒肘靠北八卦也,進步退步左顧右盼中定此五行也,掤捋擠按即乾坤坎離四正方也,採挒肘靠,即巽震兌艮四斜角也,進退顧盼定即金木水火土也,

Long Boxing: it is like a long river flowing into the wide ocean, on and on ceaselessly…

The thirteen dynamics are: warding off, rolling back, pressing, pushing, plucking, rending, elbowing, bumping, advancing, retreating, stepping to the left, stepping to the right, and staying in the center. Warding off, rolling back, pressing, pushing, plucking, rending, elbowing, and bumping relate to the eight trigrams:

☱☰☴

☲ ☵

☳☷☶

Warding off, rolling back, pressing, and pushing correspond to ☰, ☷, ☵, and ☲ in the four principle compass directions [meaning simply that these are the primary techniques]. Plucking, rending, elbowing, and bumping correspond to ☴, ☳, ☱, and ☶ in the four corner directions [i.e. are the secondary techniques]. Advancing, retreating, stepping to the left, stepping to the right, and staying in the center relate to metal, wood, water, fire, and earth – the five elements.

[Commentary:]

原注云,此係武當山張三峯老師遺論,欲天下豪傑延年益壽,不徒作技藝之末也,

This relates to the theory left to us from Zhang Sanfeng of the Wudang Mountains. He wanted all the heroes in the world to live long and not merely gain skill.

一舉動周身俱要輕靈又須貫串

Once there is any movement, the entire body should be nimble and alert. There also needs to be connection from movement to movement.

練拳時不用莽力,方能輕靈,十三式須一氣串成

When practicing the solo set, if you do not use crude effort, you will then be able to be nimble and alert. It must be a single flow throughout.

氣宜皷盪神宜內歛

The energy should be roused and the spirit should be collected within.

氣不滯,則如海風吹浪,靜心凝神,斯為內歛

When the energy is not stagnant, then it is like the sea breeze blowing on the waves. When the mind is calmed and the spirit is concentrated, this is what it means to be collected within.

毋使有缺陷處毋使有凸凹處毋使有斷續處

Do not allow there to be cracks or gaps anywhere, pits or protrusions anywhere, breaks in the flow anywhere.

練拳宜求圓滿,不可參差不齊,宜緩慢而不使間斷

When practicing the solo set, you should seek roundness and fullness. It must not be uneven. It should be done slowly and without interruption.

其根在脚發於腿主宰於腰形於手指由脚而腿而腰總須完整一氣乃能得機得勢

Starting from the foot, issue through the leg, directing it at the waist, and expressing it at the fingers. From foot through leg through waist, it must be a fully continuous process, and you will then catch the opportunity and gain the upper hand.

練法須上下相隨,勁自跟起,行於腿,達於腰由脊而膊,而行於手指,周身一氣,用時進前退後,其勁乃不可限量矣

When practicing, it is necessary for the upper body and lower to coordinate with each other. Power initiates from the heel, goes through the leg to the waist, and from the spine then goes through the arms to the fingers. As long as it is a continuous process through the whole body, then when you apply power, whether advancing or retreating, the power will be immeasurable.

有不得機得勢處身便散亂其病必於腰腿求之上下前後左右皆然凡此皆是意不在外面

If you miss and your body easily falls into disorder, the problem must be in the waist and legs, so look for it there. This is always so, regardless of the direction of the movement, be it up, down, front, back, left, right. And in all of these cases, the problem is a matter of your intent and does not lie outside of you.

病不在外而全在意,意不專則神不聚,即不能得機得勢矣

Problems do not come from outside, they all lie with your intent. If your intent is not concentrated, your spirit will not gather, and you will then be unable to catch the opportunity and gain the upper hand.

有上即有下有前即有後有左即有右如意要向上即寓下意若將物掀起而加以挫之力斯其根自斷乃壞之速而無疑

With an upward comes a downward, with a forward comes a backward, and with a left comes a right. If your intention wants to go upward, then harbor a downward intention, like when you reach down to lift up an object. You thereby add a setback to the opponent’s own intention, thus he cuts his own root and is defeated quickly and certainly.

此言與人對敵搭手時,先將彼搖動猶樹無根立脚不定,則自然倒下矣

Once you cross hands with an opponent, first get him to sway like a rootless tree so he stands on his feet unstably, and then he will naturally topple.

虛實宜分淸楚一處有一處虛實處處總此一虛實

Empty and full must be distinguished clearly. In each part there is a part that is empty and a part that is full. Everywhere it is always like this, an emptiness and a fullness.

與人對敵,每式前虛後實,如放勁則前足坐實後足蹬直,總使虛實淸楚,則變化自能如意矣

When dealing with an opponent, let each of your postures be empty in front and full behind, then when you release power the front leg sits and becomes full while the back leg straightens and becomes empty. If you always ensure that empty and full are clearly distinguished, then when you adjust you will naturally be able to do as you please.

周身節節貫串毋令絲毫間斷耳

Throughout the body, as the movement goes from one section to another there is connection. Do not allow the slightest break in the connection.

周身骨節順合氣須流通意無間斷

Every section of the body should smoothly link to the other, the energy must flow, and the intent should be uninterrupted.

–

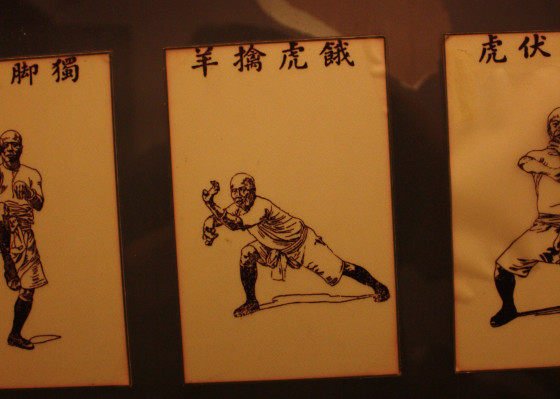

太極拳十三式

THE TAIJI BOXING THIRTEEN DYNAMICS SOLO SET

太極起式

[1] TAIJI BEGINNING POSTURE

攬雀尾

[2] CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

單鞭

[3] SINGLE WHIP

提手上式

[4] RAISE THE HANDS

白鶴亮翅

[5] WHITE CRANE SHOWS ITS WINGS

摟膝抝步

[6] BRUSH KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE

手揮琵琶式

[7] PLAY THE LUTE

左右摟膝抝步三個

[8] BRUSH KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE THREE TIMES – LEFT & RIGHT

手揮琵琶式

[9] PLAY THE LUTE

進步搬攬錘

[10] ADVANCE, PARRY, CATCH, PUNCH

如封似閉

[11] SEALING SHUT

十字手

[12] CROSSED HANDS

抱虎歸山

[13] CAPTURE THE TIGER AND SEND IT BACK TO ITS MOUNTAIN

肘底看錘

[14] BEWARE THE PUNCH UNDER ELBOW

左右倒輦猴

[15] RETREAT, DRIVING AWAY THE MONKEY – LEFT & RIGHT

斜飛式

[16] DIAGONAL FLYING POSTURE

提手上式

[17] RAISE THE HANDS

白鶴亮翅

[18] WHITE CRANE SHOWS ITS WINGS

左摟膝拗步

[19] BRUSH KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE – LEFT

海底針

[20] NEEDLE UNDER THE SEA

山通臂

[21] MOUNTAIN THROUGH THE ARMS

撇身錘

[22] FLINGING BODY PUNCH

上步搬攬錘

[23] STEP FORWARD, PARRY, CATCH, PUNCH

攬雀尾

[24] CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

單鞭

[25] SINGLE WHIP

左右抎手

[26] CLOUDING HANDS – LEFT & RIGHT

單鞭

[27] SINGLE WHIP

高探馬

[28] RISING UP AND REACHING OUT TO THE HORSE

左右分脚

[29] KICK TO THE RIGHT SIDE – LEFT & RIGHT

轉身蹬脚

[30] LEFT TURN, PRESSING KICK

左右摟膝抝步

[31] BRUSH KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE – LEFT & RIGHT

進步栽錘

[32] ADVANCE, PLANTING PUNCH

翻身二起

[33] TURN AROUND, DOUBLE KICK

左右披身伏虎式

[34] COVER THE BODY WITH FIGHTING TIGER POSTURE – LEFT & RIGHT

囘身蹬脚

[35] TURN AROUND, PRESSING KICK

雙風貫耳

[36] DOUBLE WINDS THROUGH THE EARS

左蹬脚

[37] LEFT PRESSING KICK

轉身右蹬脚

[38] TURN AROUND, PRESSING KICK

上步搬攬錘

[39] STEP FORWARD, PARRY, CATCH, PUNCH

如封似閉

[40] SEALING SHUT

十字手

[41] CROSSED HANDS

抱虎歸山

[42] CAPTURE THE TIGER AND SEND IT BACK TO ITS MOUNTAIN

斜單鞭

[43] DIAGONAL SINGLE WHIP

左右野馬分鬃

[44] WILD HORSE VEERS ITS MANE – LEFT & RIGHT

上步攬雀尾

[45] STEP FORWARD, CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

單鞭

[46] SINGLE WHIP

玉女穿梭

[47] MAIDEN WORKS THE SHUTTLE

上步攬雀尾

[48] STEP FORWARD, CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

單鞭

[49] SINGLE WHIP

抎手

[50] CLOUDING HANDS

單鞭下勢

[51] SINGLE WHIP, LOW POSTURE

金鷄獨立

[52] GOLDEN ROOSTER STANDS ON ONE LEG

左右倒輦猴

[53] RETREAT, DRIVING AWAY THE MONKEY – LEFT & RIGHT

斜飛式

[54] DIAGONAL FLYING POSTURE

提手上式

[55] RAISE THE HANDS

白鶴亮翅

[56] WHITE CRANE SHOWS ITS WINGS

摟膝抝步

[57] BRUSH KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE

海底針

[58] NEEDLE UNDER THE SEA

山通臂

[59] MOUNTAIN THROUGH THE ARMS

白蛇吐信

[60] TURN AROUND, WHITE SNAKE FLICKS ITS TONGUE

上步搬攬錘

[61] STEP FORWARD, PARRY, CATCH, PUNCH

進步攬雀尾

[62] ADVANCE, CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

單鞭

[63] SINGLE WHIP

抎手

[64] CLOUDING HANDS

單鞭

[65] SINGLE WHIP

高探馬代穿掌

[66] RISING UP AND REACHING OUT TO THE HORSE, CHANGING TO THREADING PALM

轉身十字腿

[67] TURN AROUND, CROSSED-BODY KICK

進步指襠錘

[68] ADVANCE, PUNCH TO THE CROTCH

上勢攬雀尾

[69] STEP FORWARD, CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

單鞭下式

[70] SINGLE WHIP, LOW POSTURE

上步七星錘

[71] STEP FORWARD WITH BIG DIPPER PUNCH

退步跨虎式

[72] RETREAT TO SITTING TIGER POSTURE

轉身雙擺蓮

[73] TURN AROUND, DOUBLE-SLAP SWINGING LOTUS KICK

彎弓射虎

[74] BEND THE BOW TO SHOOT THE TIGER

上步搬攬錘

[75] STEP FORWARD, PARRY, CATCH, PUNCH

如封似閉

[76] SEALING SHUT

十字手

[77] CROSSED HANDS

合太極

[78] CLOSING TAIJI

以上太極拳名稱三十七全套七十八個姿式完

The complete seventy-eight posture routine above is comprised of thirty-seven distinct postures.

身法

RULES FOR THE BODY

提起精神

[1] Raise the spirit.

虛靈頂勁

[2] Forcelessly press up your headtop.

含胸拔背

[3] Contain the chest and pull up the back.

鬆肩墜肘

[4] Loosen the shoulders and drop the elbows.

氣沉丹田

[5] Energy sinks to the elixir field.

手與肩平

[6] The hands are at shoulder level.

胯與膝平

[7] The hips are at knee level.

尻道上提

[8] Tuck in the anus.

尾閭中正

[9] The tailbone is centered.

內外相合

[10] Inside and outside merge together.

練法

RULES FOR PRACTICE

不强用力

[1] Do not forcefully apply power.

以心行氣

[2] Use the mind to move energy.

步如貓行

[3] Step like a cat.

上下相隨

[4] The upper body and lower coordinate with each other.

呼吸自然

[5] The breathing is natural.

一線串成

[6] The whole thing is a single thread throughout.

變換在腰

[7] Changes are in the waist.

氣行四肢

[8] Energy travels to the four limbs.

分淸虛實

[9] Clearly distinguish empty and full.

圓轉如意

[10] Turn with roundness and facility.

練演法

TRAINING THE PERFORMANCE OF THE TECHNIQUES:

太極拳起勢預備

TAIJI BOXING BEGINNING POSTURE – PREPARATION

「說明」此為太極拳出勢預備動作之形勢站定時頭宜正直內含頂勁眼向前平視胸微內含脊背拔起不可前俯後仰两肩下沉两肘微坐两手下埀指尖向前掌心向下腰胯稍鬆两足距離與两肩相齊在此時精神內固氣沉丹田一任自然不可造作守我之靜以待敵人之動然人每於此姿勢容易忽畧殊不知無論練法用法俱不得脫此望閱者學者首當於此注意焉

Explanation:

This is Taiji Boxing’s opening posture, the shape you assume in preparation for movement. While standing stably, the head should be held erect, drawn in and pressed up, the gaze straight ahead. The chest is slightly hollowed and the back pulled up. There must be no leaning forward or back. The shoulders sink, the elbows slightly sit, and the hands hang with fingers forward and palms down. The waist and hips loosen, and the feet are shoulder width apart. Spirit is now consolidated within and energy is sinking to the elixir field. Let it happen naturally, for you cannot make it happen. I preserve my stillness to await the opponent’s movement. However, people typically are liable to neglect this posture, ignorant in particular that regardless of whatever technique is being practiced or applied, none of them can be disassociated from this one. I hope the reader or student will give it first priority and pay attention to it.

第一節 攬雀尾掤法

1. CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL – WARD-OFF TECHNIQUE

「說明」由太極拳出勢起設敵人對面用左手擊我胸部我將右足就原位稍往外轉動坐實隨起左足往前踏出一步屈膝坐實後腿伸直两脚左實右虛同時將左手提起起至胸前手心向內肘尖畧埀即以我之腕貼在彼之肘腕中間用混勁往前往上掤去不可露呆板平直之像則彼之力旣為我移動彼之部位亦自不穩矣

Explanation:

From Taiji Boxing’s opening posture, if an opponent in front of me uses his left hand to strike my chest, I turn my right foot slightly outward where it is and sit full on it, then lift my left foot a step forward, and bend my knee and sit full on it while my rear leg straightens. My feet are now left full, right empty. At the same time, my left hand lifts until in front of my chest, palm inward, elbow slightly hanging, and I use my wrist to stick to his forearm, using a horizontal energy to ward off forward and upward. I must not stiffen and try to match him. The result of all this is that the opponent’s force will thus finish, and then when I move, his position will naturally destabilize.

第二節 攬雀尾捋法

2. CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL – ROLLBACK TECHNIQUE

「說明」由前勢設敵人用右手擊我右側肋部我即將右足向右前邁出屈膝踏實左脚變虛身亦同時向右抝轉眼隨往前看左右手同時圓轉往前出動右手在前手心側向裏左手在後手心側向下轉至右手心向下左手心向上時速將我右腕裏面貼彼肘上臂部外側左腕外面貼彼肘下臂部外側全身坐在左腿左脚變實右脚變虛往我胸前左側捋之則彼之身法即隨之傾斜矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent uses his right [left] hand to strike my right ribs, I step forward to the right with my right foot, bending the knee to make that foot full as my left foot becomes empty. At the same time, my body turns to the right, my gaze going forward. My hands at the same time turn over and go forward, right hand in front, palm sideways and inward, left hand behind, palm sideways and downward. My right palm now turns downward and my left palm turns upward, the inside of my right wrist quickly sticks by his elbow at the outer side of his upper arm, and the outside of my left wrist sticks by his elbow at the outer side of his lower arm. My whole body sits on my left leg, my left foot becoming full, my right foot becoming empty, as I roll back to the left in front of my chest. The result is that the opponent’s body will lean to the side.

第三節 攬雀尾擠法

3. CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL – PRESSING TECHNIQUE

「說明」由前勢設敵人往囘抽其臂我即屈右膝右脚變實左腿伸直左脚虛腰身長起隨之前進眼神亦隨往前畧往上看去同時速將右手心翻向上向裏左手心翻向下合於我之右腕上乘其抽臂之際往出擠之則敵必應手而跌矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent pulls back his arm, I promptly bend my right knee, the foot becoming full, straighten my left leg, the foot becoming empty, and lengthen my torso into the forward advance, my gaze following forward and slightly upward. At the same time, I quickly turn over my right palm upward and inward, and turn over my left palm downward and join it to my right wrist. I take advantage of the moment he pulls his arm back by pressing outward. The result is that the opponent will inevitably stumble away.

第四節 攬雀尾按法

4. CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL – PUSHING TECHNIQUE

「說明」由前勢設敵人乘勢來擠我即將两腕畧往上用提勁手指向前手心向下沉肩墜肘坐腕含胸全身坐於左腿速用两手閉其肘及腕部向前按去屈右膝右脚實伸左腿左脚虛腰亦同時往前進攻眼神隨往前畧往上看去則敵人即往後跌出矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent takes advantage of the momentum and attacks me with a press, I send both my wrists slightly upward with a lifting energy, fingers forward, palms down. I am sinking my shoulders, dropping my elbows, sitting my wrists, hollowing my chest, and my whole body is sitting on my left leg. I quickly use both hands to seal off his forearms and push forward, bending my right knee, making the right foot full, straightening my left leg, making the left foot empty, my torso going forward with the attack, my gaze following forward and slightly upward. The result is that the opponent stumbles back.

第五節 單鞭用法

5. Application of SINGLE WHIP

「說明」由前勢設敵人從我身後來擊我將右手五指合攏下埀作弔手式以稱左手之勢右足就原地向左轉動左足提起往前偏左落下屈膝坐實右腿伸直右脚虛身由右往左進轉同時左手向裏由面前經過往左伸伸至手心朝外時向彼之胸部臂去則敵人必仰身而倒然鬆肩墜肘坐腕眼神隨往前看俱要同時合作自得之

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent attacks me from behind, I gather together the fingers of my right hand to make a “hanging hand”. My right foot stays where it is but turns to the left. My left foot lifts and goes forward, coming down to the left. I bend the knee and sit full, and my right leg straightens, making my right foot empty. While my body turns from the right to the left, my left hand goes inward, passes my face, and extends to the left. Once the palm is outward, it attacks his chest. The result is that the opponent will inevitably lean back and fall away. [As my palm goes to his chest,] the loosening of my shoulders, dropping of my elbows, sitting of my wrists, and my gaze following forward should all be coordinated with each other.

第六節 提手上式用法

6. Application of RAISE THE HANDS

「說明」由前勢設敵人自右側來擊我即將身由左向右側囘轉左足隨向右移轉右足提向前進步移至左足前脚跟着地脚掌虛懸全身坐在後左腿上胸含背拔腰鬆眼前視同時將两手互相往裏提合两手心側對右手在前左手在後两手矩離約七八寸許提至两腕與敵之肘腕相合時須含蓄其勢以待敵人之變動或即時將右手心反向上用左手掌合於我右腕上擠出亦可其身法步法各動作與前擠法畧同

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent attacks from my right side, my body turns from the left to the right, my left foot goes along with it and turns to the right, and my right foot lifts and advances a step in front of my left foot, heel touching down, sole lifted. My whole body sits on my left leg, my chest is hollowed, my back is pulled up, my waist is loosened, and my gaze is forward. At the same time, my hands go inward toward each other, lifting and closing in, palms toward each other, right hand forward, left hand behind. The distance between my hands is about seven or eight inches. Once I have lifted until my wrists connect to his elbow and wrist, I must hollow and store in with my posture to await his adjustments. Or I can turn my right palm up and use my left palm to cover my right wrist and apply a pressing technique to send him out, in which case the body method, footwork, and movement is the same as the pressing technique as previously described.

第七節 白鶴亮翅用法

7. Application of WHITE CRANE SHOWS ITS WINGS

「說明」由前勢設敵人從我身前用雙手來擊我速將右脚提起向左前方踏出脚跟着地稍往裏轉膝微屈坐實身隨右脚同時向正面轉左脚移至右脚前脚尖點地两手隨右脚同時動作左手由右而左而上落至胸前手心向下右手隨落隨轉至腹前手心朝上左手手急往下往左側展開彼之右腕右手同時往上往右側展開彼之左腕則彼之力即而分散不整矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent from in front of me [on my left] uses both fists to strike, I quickly lift my right foot and step to the forward left, heel touching down, foot slightly turned inward, then my knee slightly bends and I sit full on the leg. My body is going along with my right foot and turning to face squarely to the left, and my left foot shifts to be in front of my right foot, toes touching down. My hands go along with my right foot, my left hand going from the right to the left, up, then down in front of my chest, palm down, while my right hand lowers in accordance with the turn until in front of my belly, palm up. My left hand continues downward to my left side to spread away his right wrist, while my right hand continues upward to my right side to spread away his left wrist. The result is that the opponent’s force is scattered.

第八節 摟膝抝步用法

8. Application of BRUSH KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE

「說明」由前勢設敵人從我左側下方用手或足來擊我將身往下一沉實力暫寄於右腿左足提起向前踏出一步屈膝坐實右足變虛左手同時上提由內向下將敵人之手或足摟至左膝外右手亦同時隨下落隨往身後右側圓轉而上至耳旁掌心朝前沉肩墜肘坐腕腰前進眼神亦隨之前看向敵人之胸部伸出按去則敵人自跌

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent uses his hand or foot to strike me low from my left side, I sink my body, temporarily putting all my strength into my right leg, my left foot lifts and steps forward, I then bend the knee and sit full, and my right foot becomes empty. At the same time, my left hand lifts inward and comes down to brush aside his hand or foot to the left until my hand is to the outside of my left knee. Also at the same time, my right hand goes along by lowering behind me to my right then arcing up to be beside my ear, palm forward. I sink my shoulders, drop my elbows, sit my wrists, advance with my torso, my gaze following forward, and reach out to push his chest. The result is that the opponent naturally stumbles away.

第九節 手揮琵琶式用法

9. Application of PLAY THE LUTE

「說明」由前勢設敵人用右手來擊或按我胸部含胸屈膝坐實左脚隨往後稍提脚跟着地脚掌虛懸右手同時往後合收緣彼腕下繞過即以我之腕黏貼彼之腕隨用手攏合其腕內部往右側下採捺之左手亦同時由左往前往上合收以我掌腕中黏貼彼之肘部往右分錯之或两手心前後側相映如抱琵琶狀蓄我之勢以觀其變

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent uses his right hand to strike or push my chest, I hollow my chest, bend my [right] knee and sit full, my left foot lifting slightly to the rear, heel touching down, sole pulled up. My right hand at the same time draws back to coil around under his wrist, and using my wrist to stick to his wrist, I take hold to the inside of his wrist and pluck it down to my right side. My left hand at the same time goes forward and upward from my left to gather in, using my palm near the wrist to stick to his elbow and twist it to the right, or both of my hands can move toward each other. It looks like holding a lute. I now contain my posture to observe how he adjusts.

第十節 摟膝抝步用法

10. Application of BRUSH KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE

(動作及用法與第八節畧同)

The movement and application are similar to 8.

第十一節 右摟膝用法

11. Application of RIGHT BRUSH KNEE

「說明」由前勢設敵人以左手或左足自下方來擊我即將右足向前邁出一步屈膝坐實身隨右足抝轉前進左足不動變虛急將右手屈囘由內將敵人左手或左足摟至右膝外左時同時往身後左側圓轉至耳旁掌心朝前向敵人胸部按去則敵人自倒肩腕及眼神與摟膝拗步同身手足俱要同時合作

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent uses his left hand or left foot to strike me from below, I promptly lift my right foot and step forward, then bend the knee and sit full, my body going along with my right foot by twisting to advance forward. My left foot stays where it is and becomes empty, my right hand drawing back inward, then brushing aside his left hand or left foot to the right until my hand is to the outside of my right knee. At the same time, [my left hand] goes behind me to my left then arcs until beside my ear, palm forward, then pushes toward his chest. The result is that the opponent naturally topples. My shoulders, wrists, and gaze are the same as in 8. My body, hands, and feet should all be operating together.

第十二節 左摟膝拗步

12. LEFT BRUSH KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE

動作用法與右摟膝相同

The movement and application are the same as RIGHT BRUSH KNEE.

第十三節 手揮琵琶式

13. PLAY THE LUTE

與第九節同

Same as 9.

第十四 進步搬攔捶用法

14. Application of ADVANCE, PARRY, BLOCK, PUNCH

「說明」由前式設敵人用右手來擊我即將左足微往後左側移動腰膸往左拗轉右足隨往前右側提出變成拗步踏實腰亦隨往右轉两手同時稍往左向右往裏圓轉屈囘右手變拳向敵人腕上粘貼繞手心朝上將敵腕叠住或往右脅旁稍採左手隨腰轉動時由後左側囘轉向上經過左耳旁向前往裏用肘腕中間將敵肘部裏曲用粘合之勁往外搬住手心反向下指尖略埀向上亦可左足隨往前進一步屈膝坐實右拳隨即向敵胸部擊去右足變虛眼前看腰隨進攻則敵人自應手而顚躓矣如敵臂乘我搬時欲往上滑轉我速往上翻手腕攔之可也

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent uses his right hand to strike me, I promptly shift my left foot slightly back on my left side, my waist twisting to the left. My right foot then lifts and goes forward on my right side, coming down turned outward and I sit full on it, my waist twisting to the right. My hands at the same time go slightly to the left and then arc inward to the right, my right hand drawing back and becoming a fist which sticks to and coils over his wrist, palm up, to either pile upon his wrist or slightly pluck him toward my right flank. While my waist is turning, my left hand returns upward from my rear left, passing my left ear, going forward and inward, and I use my forearm to connect to the inside bend of his elbow and move his arm outward, my palm turned down, fingers slightly hanging over. My left foot is able to advance a step while this is happening, and I bend the knee and sit full as my right fist strikes his chest, my right foot becoming empty. My gaze is forward and my waist advances with the attack. The result is that the opponent is easily made to stumble away. If he takes advantage of the moment I am moving his arm aside and tries to slip his arm over on top of mine, I can quickly flip my hand upward to block it at my wrist.

第十五節 如封似閉用法

15. Application of SEALING SHUT

「說明」由前式設敵人以左手握我右拳我即將左手心緣我右肘外面向敵左手腕格去右拳伸開向懷內抽撤撤至两手心朝裏如十字形同時含胸坐胯隨即分開變為两手心向外將敵肘腕封閉左向着其腕右手着其肘急用長勁按出眼前看腰進攻左腿仍屈膝坐實右腿伸直變虛則敵必往後仰仆矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent uses his left hand to grab my right fist, I promptly send my left hand along the outside of my right elbow to obstruct his left wrist. I open my right fist and draw it back toward my chest until both my palms are inward and making an X shape. At the same time, I hollow my chest and sit my hips, spreading my hands and turning them outward to seal off his elbow and wrist, my left hand touching his wrist, my right hand touching his elbow, and quickly applying a long energy, I push him out. My gaze is forward, my waist advances into the attack, and my left leg has again bent at the knee to sit full while my right leg has straightened and become empty. The result is that the opponent inevitably falls back facing upward.

第十六節 十字手用法

16. Application of CROSSED HANDS

「說明」設有敵人由右側自上打下我急往右轉身两脚合步两手由下往上合起作十字形手心朝裏將敵之臂部掤住如敵變雙手按來我即用雙手將敵雙手由內往左右分開手心朝上向下均可同時腰膝稍鬆往下一沉則敵人之力自散而不整矣

Explanation:

If an opponent from my right strikes down from above, I quickly turn my body to the right and bring my feet together, lifting my hands from below to join and make an X shape, palms inward, and ward off his arm. If he changes his attack to a push with both hands, I promptly use both my hands to spread his hands outward from the center, my palms either upward or downward. At the same time, my waist and knees slightly loosen and sink. The result is that the opponent’s force will naturally be scattered.

第十七節 抱虎歸山用法

17. Application of CAPTURE THE TIGER AND SEND IT BACK TO ITS MOUNTAIN

「說明」由前式設敵人自我後面右側用右手從下部擊來或用右足來踢我即往右側轉身出右步屈膝踏實左腿伸直變虛右手隨身轉時將敵右手或足摟至右膝外左手同時由左側往前腕轉運出向敵面部按去如敵又用左手自上打來急用左手腕由敵左手腕下繞過粘住右手同時圓轉提起用腕向敵肘上臂部貼住同時两手往懷內左側合收抱囘則敵人自站不定此時要鬆肩坐肘左足實右足虛

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent from behind me on my right side uses his right hand to strike me from below, or kicks me with his right foot, I promptly turn my body to the right side and step out with my right foot, bending the knee to sit full as my left leg straightens and becomes empty. While my body turns, my right hand brushes aside his hand or foot to the right until beyond my right knee. My left hand at the same time goes forward from my left side, the wrist rotating, to come out with a push to his face. If he then uses his left hand to strike from above, I quickly use my left wrist to coil around from below his left wrist and stick to it. My right hand at the same time lifts in an arc to stick on top of his elbow with my wrist. At the same time, my hands draw back embracing toward my chest on my left side. The result is that the opponent’s stance will naturally be destabilized. It is important for me to loosen my shoulders and sit my elbows. My left foot is now full, my right foot empty.

第十八節 抱虎歸山內之三式

18. THREE TECHNIQUES WITHIN CAPTURE THE TIGER AND SEND IT BACK TO ITS MOUNTAIN [ROLLBACK, PRESS, PUSH]

第十九節 肘底看錘用法

19. Application of BEWARE THE PUNCH UNDER ELBOW

「說明」由前勢如敵人自後方用右手來擊我即將右足向左移動坐實身隨之轉動胸含背拔頭頂腰腰鬆左足當身將轉過正面時提起落下脚跟着地脚掌虛朝前两手隨轉身同時動作左手側向裏肘隨肩鬆由左往後側平圓轉轉至正面我之腕臂敵腕臂相交隨自上黏合繞過下面用虎口緊抱其上肘手心向內畧往上托右手隨握拳轉至右脅下虎口朝上向敵人脅部打出眼神前看

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent from behind me uses his right hand to strike me, I promptly shift my right foot to the left and sit full, my body turning, chest hollowing, back pulling up, headtop pressing up, waist loosening. Before my body has turned to be square to him, my left foot lifts and lowers, heel touching down, sole up to face forward. My hands move along with the turning of my body. My left hand is turning inward, elbow dropping, shoulder loosening, and goes to my left rear in a level arc until I am square to him, and my forearm connects with his forearm. Then from above, my left hand stickily coils around underneath and uses the tiger’s mouth to wrap his elbow, palm inward, and slightly prop it up. My right hand has grasped into a fist and arced to my right ribs, tiger’s mouth upward, and strikes to his flank. My gaze is forward.

第二十節 倒輦猴左式用法

20. Application of RETREAT, DRIVING AWAY THE MONKEY – LEFT

「說明」由前式敵人用右手當胸打來我即將左手腕中間向敵右肘部裏曲處用半圓黏合沉勁向左往外摟出則敵必隨之往左傾斜左脚隨往後退坐實頭頂肩鬆背拔胸含右脚不動變虛右手同時往後右側環轉而以上備敵人用左手來擊

Explanation:

From the previous posture, the opponent uses his right hand to strike my chest, so I promptly send the inside of my left wrist to the inside of his right elbow, sticking and sinking down in a half circle to brush away outward to the left. The result is that he will inevitably lean to the left. My left foot steps back and I sit full, my head pressing up, shoulders loosening, back pulling up, chest hollowing, and my right foot stays where it is and becomes empty. My right hand at the same time arcs to the right rear and then upward to prepare for the opponent attacking with his left hand.

第二十一節 倒輦猴右式用法

21. Application of RETREAT, DRIVING AWAY THE MONKEY – RIGHT

「說明」由左勢設敵人以左手來擊我即將右手往前畧往下用腕中間粘合敵人肘部裏曲向右往外化出其身法步法與各姿勢均與左式同練法退三步五步七步均可但右手祗至前為止

Explanation:

From the left posture, if the opponent uses his left hand to strike me, I promptly send my right hand forward and slightly downward, using the inside of my wrist to connect with the inside of his elbow and neutralize outward to the right. The methods of body and step are the same as on the left side. When practicing the solo set, you can retreat three steps, five, or seven, so long as your right hand is in front when you stop.

第二十二節 斜飛式用法

22. Application of DIAGONAL FLYING POSTURE

「說明」由前式如敵人自右側面向我上部打來我急用右臂向敵人右臂外側掤右足同時向右側出步如敵人用下壓我臂腕我即乘勢往下稍沉勁隨即將左手上提提至敵腕上面手心向下貼合其腕往我左側略施採意左足暫坐實隨將右手向敵右臂下抽出順勢用腕部側面向敵上脅挒去手心側向裏右脚變實左脚為虛眼神隨去身亦右攻則敵自歪而倒矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent attacks me above from my right side, I quickly use my right arm to ward off to the outside of his right arm, my right foot at the same time stepping out to my right side. If he presses down my right wrist, I take advantage of the momentum, sinking down and promptly lifting my left hand onto his wrist, palm down, sticking to his wrist with an intention of slightly plucking to my left side. I temporarily sit full on my left foot, then thread my right hand under his right arm and, using the side of my wrist, rend away toward his upper flank, palm inward. My right foot is now full, left foot empty. My gaze follows along with my body’s attack to the right. The result is that the opponent naturally leans and topples away.

第二十三節 提手用法同前

23. Application of RAISE THE HANDS (same as before)

第二十四節 白鵝亮翅用法同前

24. Application of WHITE GOOSE SHOWS ITS WINGS (same as 7)

第二十五節 摟膝拗步用法同前

25. Application of BRUSH KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE (same as before)

第二十六 海底針用法

26. Application of NEEDLE UNDER THE SEA

「說明」由前式設敵人用右手將我右腕牽動我即屈右肘將手腕往囘一提手心向左左脚隨之收平脚尖點地右脚坐實如敵再將我手腕往下採去我即將右腕順勢鬆勁往下一沉腰隨坐下身往前囘俯下低眼神前視左腿仍虛則敵人之手力自懈

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent uses his right hand to pull my right wrist, I promptly bend my right elbow and draw back my wrist, lifting it up, palm to the left, my left foot withdrawing, toes touching down, my right foot sitting full. If he again tries to pluck my wrist down, I promptly loosen my wrist and sink down, my waist sitting and my body leaning forward. My gaze is forward and my left leg remains empty. The result is that the opponent’s force is naturally drained away.

第二十七節 扇通臂用法

27. Application of FAN THROUGH THE ARMS

「說明」由前勢設敵人又用右手來擊我同時急將右手由前往上往右提起起至右額角旁隨起隨將手心翻向外以托敵右手之勁左手同時提至胸前用手掌冲開之勁向敵脅部撑去可沉肩墜肘坐腕鬆腰左脚同時向前踏出屈膝坐實脚尖朝前右腿伸直變虛身正向右含騎馬襠式惟眼神隨左手前看則敵人自不能支持矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent now uses his right hand to strike, I quickly lift my right hand up and to the right until beside my right temple, my palm turning outward to prop up his right hand. My left hand at the same time lifts until in front of my chest and, using the palm, thrusts out to brace away his flank. I should be sinking my shoulders, dropping my elbows, sitting my wrists, and loosening my waist. My left leg at the same time steps out forward, bending the knee to sit full, toes forward, right leg straightening and becoming empty. My body is squared to the right almost in a horse-riding stance, but my gaze is in the direction of my left hand. The result is that the opponent is naturally rendered incapable of defending.

第二十八節 撇身捶用法圖

28. Application of FLINGING BODY PUNCH

「說明」由前式設敵人自身後照脊背或脅間用右手打來時我即將右足抬起向後偏右移動落下足尖向前變實右足尖虛向右轉變虛腰身隨轉入正面右手同時由上圜轉向右肋側落下隨握拳用腕部外面手心朝上將敵右手腕叠住同時左手圓轉由左側收囘胸前急向敵人伸去

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent from behind me uses his right hand to attack my spine or flank, I promptly lift my right foot and shift it to my right rear, bringing it down with the toes forward and it becomes full. My left toes turn to the right and the foot becomes empty as my body turns to be square to him. My right hand at the same time arcs from above to come down beside my right ribs, grasping into a fist, and using the outside of the wrist, palm upward, to pile upon his wrist. At the same time, my left hand arcs from my left side, withdrawing in front of my chest, and then quickly extends toward him.

第二十九節 進步搬攔捶用法

29. Application of ADVANCE, PARRY, BLOCK, PUNCH

說明」由前勢設敵人將被叠之手向左用力撥時我之右手腕稍隨鬆勁急用左肘腕中間向敵右肘裏曲貼往外搬開肘尖略向上手心朝外指尖略向下隨用右捶直向敵之胸部打去此時左足向前邁出一步屈膝坐實右足尖就原地稍向右移轉變虛眼前看腰進攻則敵自往後跌出矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if when I have piled onto the opponent’s wrist he forcefully deflects me to my left, my right wrist slightly goes along with it and loosens, and I quickly send my left forearm to connect with the inside bend of his right elbow and move it outward, my elbow slightly up, palm outward, fingers slightly downward. Then I use my right fist to punch straight to his chest, my left foot taking a step forward, the knee bending to sit full, my right foot staying where it is but turning to the right and becoming empty. My gaze is forward and my waist advances with the attack. The result is that the opponent naturally will stumble away.

第三十節 上步攬雀尾用法同前

30. Application of STEP FORWARD, CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL (same as before)

上為攬雀尾內之捋擠按三式

Includes as before the three techniques of rollback, press, and push.

第三十一節 單鞭式用法同前

31. Application of SINGLE WHIP (same as before)

第三十二節 抎手用法右式

32. Application of CLOUDING HANDS – RIGHT

「說明」由前勢設敵人自前面右側用右手擊我胸部或脅部我即將右手落下手心向裏由左而上往右翻轉抎出至敵腕臂外間手心向下往右化去左手同時隨落下手心向下隨往右抎去身亦隨右手拗轉眼神亦同時看去右足往右側挪步坐實左足亦畧有向右移動之意稍虛則敵之位置自然錯亂矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent from in front of me on my right side uses his right hand to strike to my chest or flank, I promptly send my right hand down, palm inward, then from the left going upward to the right, turning over and clouding outward until reaching the outside of his wrist or forearm, my palm down, and neutralizing to the right. My left hand at the same time lowers, palm down, and then clouds to the right, my torso twisting along with my right hand. My gaze at the same time goes outward, my right foot moving a step to the right side and sitting full. My left foot slightly shifts to the right and becomes slightly empty. The result is that the opponent’s position naturally falls into disorder.

第三十三節 抎手左式

33. CLOUDING HANDS – LEFT

左右用法同自悟方向而已

Same thing in the other direction.

第三十四節 單鞭用法同前

34. Application of SINGLE WHIP (same as before)

第三十五節 高探馬用法圖

35. Application of RISING UP AND REACHING OUT TO THE HORSE

「說明」由單鞭式設敵人用左手自我左腕下繞過往右挑撥我隨將左手腕略鬆勁手心朝上將敵腕叠住往懷內採囘左脚同時提囘脚尖着地鬆腰含胸右腿稍屈膝坐實同時急將右手由後而上圓轉向前往敵人面部用掌探去眼前看脊背略含有探拔前進之意

Explanation:

From the SINGLE WHIP posture, if the opponent uses his left hand to coil around from under my left wrist to prop it up and deflect it to my right, I then slightly loosen my left wrist, palm up, pile it upon his wrist, and draw it back plucking inward. My left foot at the same time lifts and withdraws, toes touching down, while loosening my waist, hollowing my chest, and my right leg slightly bending at the knee and sitting full. At the same time, my right hand quickly arcs up from behind and goes forward to his face, using my palm to strike him away. My gaze is forward and my back is slightly convex with the intent of reaching forward into the attack.

第三十六節 右分脚用法

36. Application of KICK TO THE RIGHT SIDE

「說明」由前勢設敵人用右手接我探出之右腕我隨用右腕閉住敵之右腕墜肘沉肩即將敵左臂向左側捋去同時左手粘住敵人左腕手心向下暗有探勁左脚同時向前左側邁出坐實身隨進將右脚向左提起用脚背向敵人右脅踢去隨將两手向左右分開眼隨右手看去則敵勢自不支

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent uses his right hand to connect to my right wrist as I stretch it forward, I then use my right wrist to cover his right wrist, dropping my elbows, sinking my shoulders, and promptly plucking his left arm to my left side. At the same time, my left hand sticks to his left wrist, palm down, with a stealthy extending energy. My left foot at the same time steps out forward to the left side and sits full. My body then advances and my right foot lifts to the left and kicks his right flank with the top of the foot, my hands spreading to the sides. My gaze is in the direction of my right hand’s movement. The result is that the opponent naturally cannot hold out against me.

第三十七節 左分脚用法與右同

37. Application of KICK TO THE LEFT SIDE (same as the right)

「說明」三十七圖為左分脚與右式用法練法皆同就是左右方向不同同志將右之方法反左自己領悟就知毋須再贅無論前後凡有同樣圖左右方向自想而知矣

Explanation:

Same as 37 but with left and right reversed and oriented to the left instead of right. Understanding one side, it is not necessary to repeat it for the other. Regardless of what precedes or follows, the photo is the same thing for both sides. As for the orientation to both sides, you will understand if you think about it.

第三十八節 左轉身蹬脚用法

38. Application of LEFT TURN, PRESSING KICK

「說明」由左分脚式設敵人從身後用右手打來我即將身向左正方轉動頂勁含胸拔背鬆腰右脚就原地稍向左轉仍實左腿懸提隨腰轉時脚尖朝下向敵胸部蹬去蹬時用脚跟脚指朝上两手同時隨腰轉時由下往上捧合與左脚蹬出時向左右分開眼神隨往前看去則敵自倒矣

Explanation:

From the posture of KICK TO THE LEFT SIDE, if an opponent strikes at me from behind with his right hand, I promptly turn my body to be facing directly to the left, pressing up my headtop, hollowing my chest, pulling up my back, loosening my waist, my right foot staying where it is but slightly turning to the left and remaining full. My left leg hangs while my body turns, toes down, then kicks out to his chest using the heel, toes up. During the turn, my hands prop up together from below, and during the kick, they spread to the sides, my gaze following forward. The result is that the opponent naturally topples.

第三十九節 左摟膝用法同前

39. Application of LEFT BRUSH KNEE (same as before)

第四十節 右摟膝用法同前

40. Application of RIGHT BRUSH KNEE (same as before)

第四十一節 進步栽錘用法

41. Application of ADVANCE, PLANTING PUNCH

「說明」由前式右手摟出時設敵人用右腿踢來我即用左手將敵右腿由裏往左摟開左足同時向前邁出屈膝坐實隨將右手握拳向敵右膝擊之亦可右腿伸直變虛腰身略俯下平曲胸含眼前看則敵自站立不穩矣

Explanation:

When my right hand brushes aside in the previous posture, if the opponent uses his right leg to kick me, I promptly use my left hand to brush aside his leg to my left. My left foot at the same time steps forward and the knee bends to sit full, my right hand grasping into a fist to strike his right knee as my right leg straightens to become empty, my body bending forward but balanced, my chest hollowing, my gaze forward. The result is that the opponent’s stance is naturally destabilized.

第四十二節 翻身撇身錘用法

42. Application of TURN AROUND, FLINGING BODY PUNCH

「說明」由前勢設人用右手自身後來擊我急將身由右往後翻轉轉入正面右手同時提起由左往右圓轉屈肘用腕將敵腕叠住手心朝上暗用採勁左手同時轉過胸前向敵人面部用掌跟挒去左足尖向右稍轉動右腿速提起向前右側落下坐實左腿變虛眼神隨往前看去

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent uses his right hand to attack me from behind, I quickly turn to my right rear to be square to him. My right hand at the same time lifts and arcs from left to right, bending my elbow and using my wrist to pile upon his wrist, palm up, with a stealthy plucking energy. My left hand at the same time arcs past my chest and, using the heel of the palm, rends away to his face, my left toes slightly turning to the right, my right leg having quickly lifted to the forward right, coming down to sit full, my left leg becoming empty, my gaze following forward.

第四十三節 進步搬攔錘用法

43. Application of ADVANCE, PARRY, BLOCK, PUNCH

「說明」由前式設敵人用右臂將我右腕掤起我急將左手腕乘勢將敵右肘裏曲貼合往外搬住右手握拳向敵胸部衝出打去虎口朝上左腿向前邁步屈膝坐實右脚變虛眼前看腰進攻以上身手足各部俱要同時合作則敵必應手而倒矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent uses his right arm to ward off and lift my right wrist, I quickly take advantage of the momentum by sending my left wrist to the inside bend of his right elbow to stick to it and move it outward, my right hand grasping into a fist to thrust to his chest, tiger’s mouth up, my left leg stepping forward, bending at the knee and sitting full, my right leg becoming empty. My gaze is forward and my waist advances with the attack. My upper body, hands, and feet should all act at the same time. The result is that the opponent will easily topple.

第四十四節 右蹬脚用法

44. Application of RIGHT PRESSING KICK

『說明』由前勢設敵人用左手將我右臂向左推出此時將我右腕順勢由敵人手腕下纏裹自右往左挒開隨將右脚向敵人正面蹬出左脚尖同時向左稍轉坐實身亦隨往左轉入正面頭頂背拔眼神隨右脚蹬時看去

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent uses his left hand to push my right arm out to my left, my right wrist follows the momentum, wraps under his wrist, and rends away from right to left. Then my right foot kicks out toward him. My left foot has slightly turned to the left and sits full, my body turned to be square to my left, my head pressing up, my back pulling up, my gaze following in the direction of my right kick.

第四十五節 左打虎式用法

45. Application of FIGHTING TIGER POSTURE – LEFT

「說明」由前式設敵人由左前方用左手打來我將右足落下左足隨往左側提出屈膝坐實右足變為虛身此時畧成騎馬襠形式面向左正方两手同時落下隨落隨往左合轉用右手將敵左腕扼住往左側下採去左手變拳由左外翻轉上招至左額角旁手心向外急向敵人頭部或背部打去頭頂腰鬆眼神隨左手看去

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent from my forward [rear] left uses his left hand to strike me, I lower my right foot, step my left foot to my left, bend the knee and sit full, my right foot becoming empty. My body is now almost in a horse-riding stance, square to the left. Both hands at the same time lower and go along with the left turn, my right hand grabbing his left wrist and plucking it down to the left, my left hand becoming a fist and turning over upward from outward on the left to arrive beside my left temple, palm outward, and strike quickly to his head or back. My head is pressing up, my waist is loosening, and my gaze is following in the direction of my left hand.

第四十六節 右打虎式用法

46. Application of FIGHTING TIGER POSTURE – RIGHT

「說明」由左式設敵人自後右側用右手打來我即將右足提起向右側邁去屈膝坐實畧成跨馬式腰隨之往右側前方拗轉左腿變虛两手同時隨落隨往右合轉用左手將敵右腕扼住往右側下採去右手變拳由右外翻轉上招至右額角旁手心向外急向敵人頭部或背部打去頂勁鬆腰眼神隨右手看去

Explanation:

From the left posture, if an opponent from behind me on my right uses his right hand to strike me, I promptly lift my right foot and step out to my right side, bending the knee to sit full, almost making a horse-riding stance, my waist twisting forward to the right, my left leg becoming empty. Both hands lower and go along with the right turn, my left hand grabbing his right wrist and plucking it down to the right, my right hand becoming a fist and turning upward from outward on the right to arrive beside my right temple, palm outward, to quickly strike his head or back. My head is pressing up, my waist is loosening, and my gaze is following in the direction of my right hand.

第四十七節 囘身右蹬脚同前

47. Application of TURN AROUND, RIGHT PRESSING KICK (same as before)

第四十八節 雙風貫耳用法

48. Application of DOUBLE WINDS THROUGH THE EARS

「說明」由前勢設敵人自右側用雙手打來我急將左脚尖稍向右轉仍實右脚同時向右側懸轉膝上提脚尖朝下身同時隨轉速將两手背由上往下將敵人两腕往左右分開叠住頭頂腰鬆背拔胸含隨將两手握拳由下往上向敵人雙耳用虎口貫去右脚同時向前落下變實眼前看身畧有進攻意此時左足變虛

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent on my right side uses both fists to strike me, I quickly turn my left toes slightly to the right, the foot remaining full, my right foot hanging with the knee up, toes down, my body turning along with the movement, and quickly the backs of my hands go down from above to pile upon his wrists and spread them away to the sides. With my head pressing up, my waist loosening, my back pulling up, my chest hollowing, both my hands then grasp into fists and come up from below to strike his ears with the tiger’s mouths. My right foot at the same time lowers forward and becomes full, my gaze is forward, my torso has a slight intention of advancing into the attack, and my left foot becomes empty.

第四十九節 左蹬脚用法

49. Application of LEFT PRESSING KICK

「說明」由前式設有敵人自左側脅部來擊我急用左手將敵右手臂粘住由裏往外挒開左足同時往前招起照敵胸脅部蹬去右手隨往右分開此時右足在原地微有移動仍坐實頭頂背拔眼神隨往前看去

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent strikes to my flank from my left side, I quickly use my left hand to stick to his right arm and rend it away from inward to outward. My left foot at the same time lifts forward to kick his chest or flank, my right hand separating away to my right side. My right foot stays where it is, though slightly shifting, and remains full. My head is pressing up, my back pulling up, and my gaze follows forward.

第五十節 轉身蹬脚用法

50. Application of TURN AROUND, PRESSING KICK

「說明」接前式如有敵人從背後左側打來時我急將身往右後邊轉成正面左脚同時隨身轉時收囘隨收隨往右懸轉落下坐實脚尖向前此時右脚掌為一身轉動之樞紐两手合收隨身至正面急用右手腕將敵肘腕粘住自上而下向左挒出右脚同時招起向敵胸脅部踢去左手隨往左分開

Explanation:

Continuing from the previous posture, if an opponent attacks from my left rear, I quickly turn around to the right to face him squarely, my left foot withdrawing to hang while I turn, then coming down to sit full with the toes forward, my right sole being the pivot for the body’s turn. My hands are gathering in until my body is squared, then quickly my right hand sticks to his forearm, and goes down from above and rends away to the left. My right foot at the same time lifts and kicks to his chest or flank, my left hand spreading away to the left.

第五十一節 進步搬攔錘同前

51. ADVANCE, PARRY, BLOCK, PUNCH (same as before)

第五十二節 如封似閉同前

52. SEALING SHUT (same as before)

第五十三節 十字手同前

53. CROSSED HANDS (same as before)

第五十四節 抱虎歸山同前

54. CAPTURE THE TIGER AND SEND IT BACK TO ITS MOUNTAIN (same as before)

抱虎歸山內之三式(抱與捋不同)

Includes its three techniques of rollback, press, and push. (The capture does not mean the rollback.)

第五十五節 斜單鞭(與前方向不同)

55. DIAGONAL SINGLE WHIP (the orientation different from before)

第五十六節 野馬分鬃右式用法

56. Application of WILD HORSE VEERS ITS MANE – RIGHT

說明」由前式設敵人自右側進左步用左手打來我即將身右轉抽囘右足脚尖虛點地隨用左手將敵左腕牽住往左側下畧有採意同時急上右足屈膝坐實左足變虛隨用右腕向敵腋下分去左手亦隨之鬆開此時身隨進眼前看則敵自歪斜而不能立矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent from my right side advances with his left foot and strikes with his left hand, I quickly turn my body to the right, draw back my right foot, toes lightly touching down, then use my left hand to tug his left wrist with a slight plucking intention down to my left. At the same time I quickly step forward with my right foot, bend the knee to sit full as my left foot becomes empty, and spread my right wrist away to his armpit, my left hand loosening and spreading aside, my body advancing, my gaze forward. The result is that the opponent will naturally lean to the side and be incapable of stability.

第五十七節 野高分鬃左式用法

57. Application of WILD HORSE VEERS ITS MANE – LEFT

「說明」由右式如敵人自左前側方用右手打來我用右手將敵右腕牽制隨進左手左足餘式皆與右同

Explanation:

From the right version of the posture, if the opponent comes from my left side to attack me with his right hand, I use my right hand to tug his right wrist, then advance with my left hand and left foot, the rest the same as on the right side.

第五十八節 攬雀尾

58. CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL

第五十九節 單鞭用法同前

59. Application of SINGLE WHIP (same as before)

第六十節 玉女穿梭頭一手左式用法

60. Application of MAIDEN WORKS THE SHUTTLE – LEFT

「說明」由單鞭式設敵人從後右側用右手自上打下我即將身右轉右脚隨即提囘左脚前急用右腕將敵右腕外面掤住左脚同時前進屈膝坐實左脚虛再用左腕由敵肘腕裏面往上偏左圓活掤起隨將右手騰出向敵胸脅部按去頭頂腰鬆胸含背拔眼前看則敵自傾

Explanation:

From the SINGLE WHIP posture, if an opponent from behind me on my right side uses his right hand to strike down from above, I promptly turn my body to the right, my right foot lifting and withdrawing in front of my left foot, and I quickly use my right wrist to ward off to the outside of his right wrist. My left foot at the same time advances, bending the knee to sit full as my left [right] foot empties, and I use my left wrist to nimbly ward off upward to the inside of his forearm, my right hand coming away to push to his chest or flank. My head is pressing up, my waist loosening, my chest hollowing, my back pulling up, and my gaze is forward. The result is that the opponent naturally collapses.

第六十一節 玉女穿梭第二手右式用法

61. Application of MAIDEN WORKS THE SHUTTLE – RIGHT

「說明」接前式如敵人由身後右側用右手劈頭打來我即將左脚往裏稍轉右脚同時向後右側出步屈膝坐實身隨向後往右抝轉左脚變虛急用右腕由敵右臂外粘住往上右側掤起隨將左手向敵右脅按去則敵自倒

Explanation:

Continuing from the previous posture, if an opponent from behind me on my right side uses his right hand to chop down to my head, I promptly turn my left foot slightly inward, my right foot stepping out to my right rear, bending the knee and sitting full while my body twists around to the right rear and my left foot becomes empty. I quickly use my right wrist to stick to the outside of his right arm and ward off upward to the right, my left hand pushing to his right flank. The result is that the opponent naturally topples.

第六十二 玉女穿梭

62. MAIDEN WORKS THE SHUTTLE

三式用法與第一式同

Same as 60.

第六十三 玉女穿梭

63. MAIDEN WORKS THE SHUTTLE

四式用法與第二式同

Same as 61.

第六十四節 攬雀尾同前

64. CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL (same as before)

第六十五節 單鞭

65. SINGLE WHIP

無論前後單鞭與抎手二姿式相同練法與用法亦相同

Same as before.

第六十六節 抎手

66. CLOUDING HANDS

第六十七節 單鞭下式用法

67. Application of SINGLE WHIP, LOW POSTURE

「說明」由單鞭已出之左手如敵人以右手將我左手往外推去或用力握住我即將右腿往後坐下左手同時用圓活裹勁收囘胸前或敵用左手來擊我急用左手將敵左腕扼住往左側下採去亦可右腿與腰身同時坐下以牽彼之力而蓄我之氣

Explanation:

After the SINGLE WHIP’s left hand has come out, if the opponent uses his right hand to push my left hand outward or forcefully grab it, I promptly squat down to the rear on my right leg, my left hand nimbly wrapping to draw back in front of my chest. Or if he uses his left hand to strike, I can quickly use my left hand to grab his left wrist and pluck down to the left [right] as my right leg and body squat. By tugging on his force, I conserve my own energy.

第六十八節 金雞獨立右式用法

68. Application of GOLDEN ROOSTER STANDS ON ONE LEG – RIGHT

由上式如敵人往囘拽其力我即順勢將身向前向上鑽起右腿隨之提起用膝向敵腹部衝去右手隨之前進屈肘指尖朝上以閉敵人左手此時左脚變實穩立頭頂背拔右手隨進時或牽制敵人左右手亦可不必拘執

[Explanation:]

From the previous posture, if the opponent pulls back his energy, I promptly follow his momentum, my body going forward and drilling upward, my right leg lifting and using the knee to thrust into his belly, my right hand coming forward, bending at the elbow, fingers up, to seal off his left hand. My left foot has become full and stands stably, my head is pressing up, my back pulling up. When my right hand comes forward, it can divert either of his hands and is not restricted to one or the other.

第六十九節 金雞獨立左式用法

69. Application of GOLDEN ROOSTER STANDS ON ONE LEG – LEFT

「說明」由右式設敵人用右拳打來我右手沉下速起左手托敵肘提左腿與右理同

Explanation:

From the right posture, if the opponent uses his other hand to strike, my right hand sinks and I quickly lift my left hand to prop up his elbow, lifting my left leg to do as the right has done.

第七十節 倒輦猴同前

70. RETREAT, DRIVING AWAY THE MONKEY (same as before)

第七十一節 斜飛式同前

71. DIAGONAL FLYING POSTURE (same as before)

第七十二節 提手同前

72. RAISE THE HANDS (same as before)

第七十三節 白鶴亮翅同前

73. WHITE CRANE SHOWS ITS WINGS (same as before)

第七十四節 摟膝抝步同前

74. BRUSH KNEE IN A CROSSED STANCE (same as before)

第七十五節 海底針同前

75. NEEDLE UNDER THE SEA (same as before)

第七十六節 山通背同前

76. MOUNTAIN THROUGH THE BACK (same as 27)

第七十七節 轉身白蛇吐信

77. TURN AROUND WITH WHITE SNAKE FLICKS ITS TONGUE

此式與撇身錘同惟第二式變掌用法在指在掌耳

This is the same as the FLINGING BODY PUNCH, except that in the second photo the fist has opened into a palm, the technique now lying in the fingers and palm.

第七十八節 搬攬錘同前

78. PARRY, CATCH, PUNCH (same as before)

第七十九 攬雀尾式用法同前

79. Application of CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL (same as before)

第八十節 單鞭式用法同前

80. Application of SINGLE WHIP (same as before)

第八十一節 抎手用法同前

81. Application of CLOUDING HANDS (same as before)

第八十二節 單鞭用法同前

82. Application of SINGLE WHIP (same as before)

第八十三節 高探馬代穿掌

83. RISING UP AND REACHING OUT TO THE HORSE, CHANGING TO THREADING PALM [no explanation given, and palm name changed to PALM STRIKE TO THE FACE further below]

第八十四節 十字單擺蓮用法(即十字腿)

84. Application of CROSSED-BODY SINGLE-SLAP SWINGING LOTUS KICK (called CROSSED-BODY KICK)

「說明」由前式設敵人自身後右邊用右手横混打來我急將身向右正面抝轉左臂同時翻轉屈囘與右臂上下相映時急向身後右側探手由敵右腕裏邊往外粘去同時急將右腿提起用脚背之混勁向敵右脅部踢去則敵必應脚而出矣

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent from behind me to my right swings at me with his right hand, I quickly twist around to the right to face him squarely, my left arm turning over and drawing in. Once it and my right arm mirror each other above and below, it quickly reaches to my right rear to stick to the inside of his right wrist and take it outward while I quickly lift my right leg and kick sideways with the top of my foot to his right flank. The result is that the opponent must comply with my foot and stumble away.

第八十五節 進步指襠捶用法

85. Application of ADVANCE, PUNCH TO THE CROTCH

「說明」接前式如敵人往囘撤手時我即將右足落下同時左足前進屈膝坐實在此時設敵人再用右足自下來踢急用左手將敵右足往左膝外摟開右手隨即握拳向敵腹部指去身微俯式眼神隨之前看

Explanation:

Continuing from the previous posture, if the opponent draws back his hand, I quickly lower my right foot, step forward with my left foot, bend the knee and sit full. If he is now using his right foot to kick, I quickly use my left hand to brush it aside beyond my left knee, my right hand quickly grasping into a fist and punching to his belly. My body is slightly leaning and my gaze follows forward.

第八十六節 上步攬雀尾用法同前

86. Application of STEP FORWARD, CATCH THE SPARROW BY THE TAIL (same as before)

第八十七節 單鞭下式用法同前

87. Application of SINGLE WHIP, LOW POSTURE (same as before)

第八十八節 上步七星用法

88. Application of STEP FORWARD WITH THE BIG DIPPER

由上式設敵人用右手自上劈下我即將身向左前進两手同時集合交叉作七字形手心朝裏掤住向敵用拳直打亦可右腿在两手交叉時提起用脚背踢去左脚變實拔背含胸頭要頂勁眼神往前注視則我身自穩固矣

[Explanation:]

From the previous posture, if the opponent uses his right hand to chop down from above, I quickly advance my body forward to the left, crossing my hands together to make a Big Dipper shape, palms inward, warding off toward him, or I can use fists to strike straight forward. My right leg at the same time kicks out with the top of the foot as my left foot becomes full. I am pulling up my back, hollowing my chest, and my head should be pressing up, my gaze forward, and then my body will naturally be stable.

第八十九節 退步跨虎式用法

89. Application of RETREAT TO SITTING TIGER POSTURE

「說明」由前式設敵人再用雙手從我頭之两旁合擊我即將两腕粘在敵两腕裏邊左手往左側下方沾去右手往右側上方沾起两手心隨之反轉向外右脚隨往後落下坐實腰隨往下沉勁左足隨之稍後提脚尖點地拔背含胸頭頂勁眼神前看

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent uses both hands together to strike both sides of my head, I promptly send both my wrists to stick to the inside of his wrists, my left hand going out to the lower left, my right hand lifting to my upper right, my palms turning outward. My right foot at the same time comes down to the rear and sits full, my waist sinking down, my left foot slightly lifting, toes touching down. I am pulling up my back, hollowing my chest, and my head is pressing up, my gaze forward.

第九十節 轉身雙擺蓮用法(又名轉脚擺蓮)

90. Application of TURN AROUND, DOUBLE-SLAP SWINGING LOTUS KICK (also called SPIN ON THE FOOT, SWINGING LOTUS KICK)

「說明」由前勢設敵人自我身後用右手打來我即將右脚掌就原地向右後方抝轉身隨圓轉左脚亦隨之懸轉轉至右脚後方落下坐寔同時两手隨身合轉轉至緊挨敵右肘腕粘住隨纏繞腕之裏面往左挒去急用右脚背向敵胸脅部踢去左脚踏實鬆腰頭頂勁眼神向敵人看去右手隨往右分開

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if an opponent from behind me uses his right hand to strike, I promptly spin my body around on my right sole, my left foot hanging during the turn until it comes down behind my right foot and sits full. My hands go along with the spin of my body until they zero in on his right elbow and wrist, then wrap around to the inside of his wrist and rend away to the left as the top of my right foot quickly kicks his chest or flank. My left foot is full, I am loosening my waist, my head is pressing up, my gaze is in the direction of the opponent, and my right hand then spreads away to the right.

第九十一節 彎弓射虎用法

91. Application of BEND THE BOW TO SHOOT THE TIGER

「說明」由前式設敵人往囘撤身時我即將右手隨敵右手粘去隨繞過腕外面握拳打出左手同時沉在敵右肘彎曲處右脚隨往右落下坐實腰下沉勁如騎馬襠樣式左脚變虛

Explanation:

From the previous posture, if the opponent withdraws his body, I promptly stick to his right hand with my right hand, coiling around to the outside of his wrist, making a fist and striking. My left hand at the same time is sinking the bend of his right elbow, while my right foot lowers to the right and sits full, my waist sinking, putting me almost in a horse-riding stance, my left foot becoming empty.

如練法圖與後三十七對圖解說少有不同是各有意思皆對太極變化不能拘一

If there are any differences between these solo practice photos and the sparring photos further below, it is because each case comes with the idea that since Taiji is adaptive, you cannot be restricted to a single method.

第九十二節 進步搬攔捶(用法同前)

92. ADVANCE, PARRY, BLOCK, PUNCH (application same as before)

第九十三節 如封似閉(用法同前)

93. SEALING SHUT (application same as before)

第九十四節 由如封似閉作十字手式同前收式變為合太極