Introduction

Antagonists seem to be the critical ingredient that make the martial arts possible. Yet to understand why that is the case we need to start by unpacking a few things. An immense range of activities fall within the category that we term “martial arts,” so much so that simply defining the term is much more challenging than one might expect. Still, all of these activities are essentially social pursuits. The martial arts are really more about the pedagogy and the discussion of violence than its actual performance. Indeed, the quality of some isolated hermit’s technique cannot make them a martial artist. At a bare minimum they must be willing to pass that skill along, or perform it for others, before the label really applies.

This raises a few obvious questions. Why should one desire to be a in a community that practices or passes on these skills? What is the ultimate utility or meaning of these techniques? Or to put the question rather crassly, are the varied benefit of practicing a given martial art worth the time, cost and effort necessary to do so?

It should surprise no one that all sorts of martial arts have formulated their own answers to these types of questions. I sometimes think that indoctrinating students into their unique world view is just as important as the actual transmission of techniques. Indeed, it is an open question in my mind as to whether the martial arts, as a social and cultural construction, can even exist without some sort of world defining narrative.

Psychologists have noted that telling stories is one of the most basic ways in which humans understand, and attempt to interact, with our world. In fact, narrative seems to be key to how we as a species understand the process of causation in the world around us. Sadly, there is less evidence that the physical world that we seek to understand is structured in this way. Hence our theories and stories about the world, while certainly useful, always reveal some aspect of reality with one hand, as they hide certain things with the other. To tell stories is human, but it may not be the best way to understand quantum mechanics.

On the other hand, paying close attention to the stories that people tell may be absolutely critical when our goal is understanding the functions of the voluntary communities that individuals create. This is critical as not all groups, organizations or styles are attempting to do the same thing. Not all fighting styles claim to do the same work, or provide the same social and personal benefits.

Students of martial arts studies thus require a number of discursive keys capable of opening the door to a more serious and sustained comparative study of these functions. Sadly, the comparative method is not commonly seen within martial arts studies. Yet such studies might help us to understand why, at a given point in time, individuals are drawn to one martial art versus another. Or why do some types of martial practice thrive in a given social or economic setting, yet struggle in another?

Nothing is More Useful than a Bad Guy

This sort of positivist research generally begins when researchers sit down and begin to measure things. Typically, one will start with the martial artists themselves. You might collect data on their age, race or gender. Other socio-economic indicators can be gleaned through formal surveys or participant observation. One might conduct interviews, sample social media posts or examine their physical performance in public demonstrations or fights. Anything that can be observed can be quantified and fed into a statistical model of human behavior.

That is all great. Indeed, my earlier research relied quite heavily on data crunching and “large-N” analysis (granted, at the time I was more interested in the behavior of political parties and nation states than martial artists). Yet some of the things that are most useful for adding nuance to comparative analysis might, at first, be a little less obvious. For instance, when you walk into the average martial arts school, it is highly unlikely that anyone will self-identify as the resident villain. Yet such a figure is critical to understanding how the community functions.

This can often be seen in way that individuals discuss their styles. A good Kung Fu story is mostly a normatively loaded narrative about conflict which tends to identify one set of actors with positive social traits (or traits that are understood to be “good” in this situation) and another set of individuals or forces with negative ones. John Christopher Hamm has done a wonderful job of exploring the way in which the literary imaginings of these conflicts have evolved in the sorts of Wuxia fiction produced in Southern China. Late 19thcentury novels valorized the sorts of feuding between neighboring clans and villages that characterized much of Southern Chinese life. In contrast, Jin Yong’s much later novels reflected the larger scale struggle to control the “central plains” in an era when many of his readers had (like his protagonists) fled into exile.

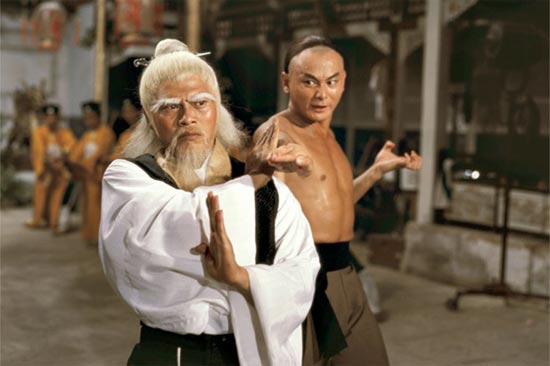

Both folklore (the burning of the Shaolin temple by the Manchus) and film (Bruce Lee’s perpetual struggle against the markers of racial injustice and imperialism), offer a wide range of antagonists for our consideration. Indeed, film studies scholars are correct in noting that the sorts of villains that films present, from the fear of brainwashing in the Cold War to the distrust of social and political institutions in the wake of Vietnam, can tell us a good deal about a society’s values and preoccupations.

Comparing the sorts of villains that appear in two different genera of martial arts films (say, the current run of John Wick stories, and Hong Kong Wuxia films of the 1960s) would doubtless be an informative, rewarding and enjoyable exercise. A scaled down version of this might even make a great blog post. Yet ultimately these films are meant to appeal to a general audience. While they are certainly watched by some martial artists, they are primarily reflective of larger social trends.

Again, what would be most interesting would be the comparative case study. How do the smaller scale narratives produced within the martial arts community, for its own exclusive consumption, reflect or contradict these larger sets of social anxieties? Again, this is where we in martial arts studies might leverage our villains to collect some valuable insights about the varieties of social work performed by different types of martial arts communities. After all, I am not sure that there is any reason to expect that the stories told in an MMA gym and the children’s Taekwondo gym across the street would share the same sorts of oppositional figures.

Construction the Loyal Opposition

In purely methodological terms, how might we identify the sources of rhetorical opposition within a given community? This process will vary depending on a variety of factors, but let us begin by considering something fairly familiar, the Wing Chun community. What becomes immediately apparent is that there are actually many different sorts of overlapping villains whose image and memory students are forced to struggle with. So let’s start at the beginning.

Every webpage, how-to book and introductory seminar seems to involve some variant of the Wing Chun creation myth which typically revolves around two key antagonists. First, one must come to terms with the Manchu government which burned the Shaolin Temple, representing a sort of structural, almost metaphysical, evil. Then there is the question of the marketplace bully whom Yim Wing Chun must fight to preserve her marriage prospects.

Interpreting these stories in an early 20thcentury Cantonese context is not difficult. The first narrative evokes nationalist themes with the Manchu’s being a stand-in for various other foreign oppressors who are seen as being responsible for the chaos of the Republic period (in practice this was mostly the Japanese and the British). Meanwhile, the story of the marketplace bully is both a cautionary tale about misdirected internal opposition within the realm of Rivers and Lakes, and an object lesson in the strategic principals that will allow the Wing Chun student to overcome China’s international and structural opponents.

Deciding what it all means when these stories are translated into a Western cultural context, one in which we are not worried about Japanese imperialism in Shanghai and the Manchus have no particular cultural significance, is a much more difficult task. Given the frequency with which these stories are repeated, they must mean something to the global population of Wing Chun students. They certainly seem to serve as shared signifiers of the cultural authenticity of one’s projects. Yet a variety of listeners have projected feminist interpretations onto Yim Wing Chun’s narrative, or concocted political readings of the conflict with the Qing, which would probably have greatly surprised Kung Fu students in the Pearl River Delta during the 1920s. One does not need to be a critical theorist to acknowledge that most texts can be interpreted in a varity of different ways.

While these stories are perhaps the most widely told within the Wing Chun community, they are not the only ones that are potentially revealing for the martial arts studies researcher. We might, for instance, decide to conduct personal interviews. I will never forget a conversation that I once had with two of my Wing Chun students, both old school karate guys who were a good deal older than me. Somehow the discussion turned towards the ways that casual social violence (things like barfights) had changed and largely disappeared from America’s public spaces after the 1980s.

Both of these individuals were from a large rustbelt city, and both began to reminisce fondly on the frequent bar fights that they used to get into. They immediately told a number of stories about how martial arts students from “their neighborhood” would get into fights with African American martial artists from a couple of other local schools. As the stories progressed it became clear that these were actually narratives about attempting to control a changing neighborhood recast as stereotypical martial arts tales. It became increasingly clear that when these gentlemen training in either kung fu or karate they were remembering a very specific set of opponents from their youth. Accepting this fact is critical to understanding the very specific social functions that these fighting systems served in a number of American cities during the 1970s and 1980s.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about these conversations was how upfront the two gentlemen were about the sorts of violence that they had perpetrated and also feared. It was an eye-opening experience for someone who was still relatively new to the field of martial arts studies. But in thinking about the incident it occurred to me that there are many less obvious ways in which these sorts of tales are told.

The classic “how to” books and articles which sustained the martial arts publishing industry for decades are interesting in that they contained all sorts of visual reenactments of imagined violence. Often the two fighters are randomly selected students dressed in the same school uniforms. But in a number of other cases greater budgets or imaginations allowed for a more direct visual construction of the imagined villain. Turn of the century photographs depicting the gentlemanly art of Bartitisu displayed a clear sense of class anxiety by so often portraying attackers as stereotypic muggers, mashers and tramps. On the other hand, German literature on Wing Chun in the 1970s and 1980s often took as its “loyal opposition” students of the other Asian martial arts (e.g., Karate or Taekwondo). The anxiety it responded to was not random street crime (or growing income inequality). Rather, the concern was to demonstrate that in a battle between skilled opponents (both of whom would show up wearing the proper uniforms), your arsenal of skills of would prevail.

When thinking of the social conditions that generated these two cases, it is probably significant that the first style persistently pictured its attackers as socio-economic “others,” while the second system constructed a discursive system around a more recreational model of self-defense training. This was a world in which the fundamentally similar martial artists who inhabited a rather crowded marketplace might fight for honor. Or barring that, certain sorts of magazine illustrations might help to reinforce one’s belief that their time and money had been invested in the proper sort of martial arts school.

Conclusion: The Embodied Fear

All of this is helpful, and it makes more of an art’s underlying narrative visible to the researcher. Indeed, the subconscious inflections and biases which emerge out of magazines, postcards, webpages and social media videos may be more helpful to researchers precisely because they are not interviews. The fact that we are so often unaware of how we subtly frame these more technical stories means that the resulting process may more accurately reflect the sort of work that we are actually expecting a given martial art to do.

Still, there is another level of storytelling that occurs within every martial arts system. It lays even deeper than the popular media, creation myths, or ephemera. It is expressed within the realm of embodied technique itself.

While the human body is always the same, there seems to be no end to the variety of fighting systems that surround us. This variety is the result of many factors. At the most basic level not all martial arts have the same goal. Some Chinese arts are systems of individuals self-defense (Wing Chun) while others may have been developed with an eye toward coordinated small unit military combat (the pole work of General Yu Dayou’s Sword Classic comes to mind.) Sometimes the goal of a public performance is victory in a highly competitive combat sport, while in other cases a practitioner might seek to entertain guests at a wedding or festival.

Yet even these large scale distinctions cannot explain all of the variations in the styles and approaches to combat that we see. Systems with similar goals might still have different sets of assumptions about how a fight is likely to proceed, and what sorts of skill are most important. Indeed, I am often struck by the fact that on an abstract level so many southern Chinese martial arts share a wide range of techniques. Yet they differ markedly in terms of their pedagogy and strategic assumptions. Taken as a whole, this embodied knowledge also reveals a narrative with its own set of villain(s) which may be quite useful to the practitioner.

Consider the question of grappling within Wing Chun. It is untrue that traditional Wing Chun has no grabs, locks and throws. Indeed, I was even trained in a minimal amount of ground work. But rather than attempting to wrestle and submit my opponent almost all of this was directed towards disentangling myself and being able to get back on my feet as quickly as possible. Indeed, much of the short range fighting in Wing Chun (including the afore mentioned locks and throws) seem focused on maintaining one’s ability to continue to strike and move once someone has attempted to grab you.

All of this reflects a single tactical preoccupation within the Wing Chun system. It is extremely concerned with the likely presence of multiple attackers. In these sorts of situations, one could very easily win a battle on the ground, yet lose the war. In thinking about the history of the art, it is not difficult to understand where this preoccupation came from. As a plain-clothes detective in Foshan, Ip Man was likely involved in the arrest of both violent criminal and suspected communists. During the final years of the Chinese civil war, this later group of individuals were typically tortured and killed at the end of the interrogation process. The Communist Party did not let these murders go unanswered. Its agents also put together teams that snatched various enemies of the party and treated them in broadly similar ways. In short, when Ip Man was informed that he had been added to a Communist hitlist in 1949 he probably wouldn’t have had any reason to doubt the assertion. This was a reality that all of Guangdong’s police and intelligence officers were quite familiar with.

Why then is Ip Man’s Wing Chun so focused on the possibility of multiple attacker scenarios? I would humbly suggest that the answer might be that the thing which he (and an entire generation of other practitioners) most feared was being abducted by a hit squad comprised of three to four highly trained individuals driving a Packard. Avoiding being grabbed and thrown into said Packard was the key to not being tortured to death in the back room of a safehouse somewhere in Guangzhou.

Granted, this is a very specific, historically bounded, fear. It is interesting to speculate as to whether Leung Jan’s Wing Chun had the same tactical emphasis on multiple attackers. If it did, perhaps he might have been more interested in the sorts of small unit fighting that period militia members were expected to train for, rather than the world of law enforcement and politically motivated killings that had colonized Ip Man’s imagination by 1949.

It is interesting to me how many of these half-forgotten tactical doctrines remain embodied in a wide range of martial arts. But as we think about the layers of antagonists that each system presents, in its media representations, in its oral folklore, and even in its bodily habits, we may become more conscious of these villains. Better understanding this imagined opposition can help us to not only understand what these systems were in the past, but to make more informed choices about how we interact with them, and what they might still become in the future.

oOo

If you enjoyed this reflection on villainy you might also want to read: Martial Values, Social Transformation and the Tu Village Dragon Dance

oOo