Introduction

My ongoing research on the public diplomacy of the Chinese martial arts has taken a decisive turn. The Second World War is one of those historical calamities that defines an era, and I now find myself venturing into the post-war era. This is something of an adventure for me as I have gotten rather comfortable with the first half of the twentieth century.

Adventures are fun. But any journey worth the trip is also a bit intimidating. Moving into a new era inevitably means loosening my grip on old assumptions and trying to see familiar processes through new eyes. More specifically, if we are going to understand how various Asian states engaged in “Kung Fu Diplomacy” in the 1950s and 1960s it becomes vitally important to learn a little more about the attitudes of the Western public that they were attempting to appeal to. What sorts of desires and predispositions do we find here? Why might images of the martial arts appealed to them? What did they make of updated martial arts practices the post-war period?

Such answers might help to explain some of the remaining paradoxes regarding the post-war globalization of the Asian martial arts. For instance, it makes sense that Americans would have found the Japanese martial arts more interesting than their Chinese cousins during the 1910s. Japan had just shocked the world with their defeat of Russia, and all sorts of travel writers were commenting on the rapid modernization of its society. It was inevitable that the Western public would develop an interest in their martial arts as it sought to come to terms with a newly ascendant Japan.

This is a logical, cohesive, and widely shared narrative. It also makes what happens after WWII something of a paradox. If there had been a degree of polite interest in the Japanese martial arts during the 1910s-1930s, it paled in comparison to the boom unleashed during the 1950s. Yet this was a humbled Japan, one that had been exposed as a brutal fascist power and utterly broken on the battlefield of the Pacific. China, on the other hand, had been on the winning side of this conflict and an ally (if a somewhat reluctant one) of the West. Yet American GI’s remained vastly more interested in judo than kung fu.

Perhaps Japan’s status as an occupied country after 1945 made its culture available for colonial appropriation in ways that had not really been possible in the 1920s-1930s. If nothing, else the country was hosting a sizable occupation force? Yet China’s status as a defacto colonial power in the late Qing and early Republic period did not seem to make its physical culture all that attractive to the many missionaries, government functionaries and YMCA directors that administered the Western zones of influence there.

Donn Draeger explained his interest in the Japanese martial arts by noting the superior performance of Japanese soldiers on the battlefield. Yet surely that had as much to do with their superior weapons, officers and communications systems as anything else. Something in this equation remains unexplained. Japan continued to possess a store of cultural desire (or “soft power”) that was intuitively obvious to individuals at the time. But what exactly was it? Ruth Benedict’s controversial book, the Chrysanthemum and the Sword, has been widely criticized for what it got wrong about Japanese society. Yet we still need to come to terms with its popularity. What does this say about the Western adoption of the martial arts, and their continued preference for Japanese, rather than Chinese, fighting systems in the 1950s and early 1960s. After all, it was an era when American servicemen and women were being in posted in Taiwan and all over the Pacific region. Why not a sudden interest in White Crane?

Visiting the Tiki Bar

We can shed some light on this small mystery by turning our attention to a larger paradox, emerging from the realm of architecture. In 1949 the Eames finished construction on “Case Study Number 8”, now known simply as the Eames House. This masterpiece of modern design was an experiment in using newly available “off the shelf” materials (many invented during WWII) to create functional modern dwellings to address America’s post-war housing crisis. If one were searching for a harbinger of mid-century design, something that would begin to push its simplified, functional, glass and steel lines into the mainstream of American culture, this might well be it.

Yet this was not the only architectural trend to explode in the early 1950s. At exactly the same time that Americans were building mid-century masterpieces, they were also creating thousands of cringeworthy Tiki bars. It would be hard to think of two aesthetic visions that could be more opposed to each other. Why would the flannel suit clad worshipers of America’s modernist temples spend their evenings in Tiki bars, listening to an endless supply of ethnically inspired vinyl records that inevitably featured the word “savage” in their titles?

Americans are restless spirits searching for paradise. Their popular culture has been shaped by reoccurring debates about where it is to be found, and how one might acquire such an ephemeral state. Much of the 19thcentury was invested in debates between pre and post-millennial religious movements. In the early 20thcentury these currents secularized and reemerged as a debate between what I will call “progressive modernism” and “modern primitivism.”

It was the core values of progressive moderns that the period’s architecture rendered in steel and concrete. This social movement exhibited an immense faith in the ability of technology to address a wide range of material and social challenges, and the wisdom of human beings to administer these ever more complex systems. The era that gave us the space race promised that man’s destiny lay among the stars, and it was only of matter of time until well ordered, rational, societies reached them. Of course, there were underlying discourses that found a certain expression in the 1950s. It is clear that science and modernism had been looking for a future paradise in the stars since at least the time of Jules Verne. But the 1950s threatened to make this vision a reality.

Reactions against progressive modernism also had their roots in the pre-war period. Post-impressionist artists were becoming increasingly concerned about the sorts of social alienation that technological change brought. They turned to African, Native American and Asian art as models because the abstract forms they found within them seemed to symbolize the alienation of modern individuals cut off from traditional modes of understanding. Yet these “primitive” models also offered a different vision of paradise, the promise that an early Garden of Eden could still be recovered if we were to turn our backs on a narrow vision of progress and attempt to recapture the wisdom that “primitive” communities possessed.

The current of “modern primitivism” surged again in the post-war era, a period of unprecedented economic and technological change. A wide range of thinkers once again became concerned with creeping alienation. Some noted that that an Eden could be found within. Joseph Campbell, drawing on the work of Jung and Freud, released his landmark Hero with a Thousand Facesin 1949. Rather than seeing happiness and fulfillment as something to be achieved through future progress, Campbell drew on psychological models to argue for a return to something that was timeless. The stories of forgotten and “primitive” societies were a sign post to our collective birth right. Likewise, Alan Watt’s the great popularizer of Zen Buddhism, published prolifically throughout the 1950s and 1960s, feeding an endless desire for an internal technology that could insulate us against fears of displacement, alienation and even nuclear annihilation.

It is easy to discount the Tiki Bar, to treat it as an architectural oddity. Yet it was simply a popular manifestation of a fascination with naturalism and primitivism whose genealogy stretches back to the first years of the twentieth century. The easy play with sexual innuendo and hyper-masculinity that marked these spaces makes sense when placed within the larger discourses on the stifling effects of modernism, social conformity and the need to return to a more “primitive” state to find human fulfillment. The savage was held up as someone who bore a secret vitally important to navigating those temples of glass and steel that marked the American landscape.

A Kendo Lesson

The pieces are now in place to approach the central subject of this essay. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s Canadian Club whisky ran an advertising campaign attempting to associate their product with notions of exotic travel and (luxurious) adventure. In an era when much of the advertising in the alcohol market focused on nostalgic images of hearth and home (situating the consumption of whisky within a comfortable upper-middle class heteronormativity) Canadian Club asked its drinkers to aspire to something more. It featured images of archeological expeditions to Central America, safaris in Africa, and (of course) adventures in the exotic east.

Yet the fulfillment in these adds was not simply the product of getting back to nature, or living in a more primitive condition. It was necessary to physically strive with the citizens of these realms to capture some aspect of their wisdom. At times these advertisements, each of which reads like a miniature travelogue, seem to spend as much time advertising hoplology as whiskey. Of course, nothing as prosaic as judo was featured in these adds. One did not need to join the jet set to experience Kano’s gentle art. More exotic practices, including jousting matches between Mexican cowboys, stick fighting in Portugal, and Japanese kendo were held up as the true measure of a man.

Judging from years of watching eBay auctions, the Kendo campaign was Canadian Clubs most successful of their excursions into hoplology. Or, more accurately, people have been more likely to preserve the Kendo advertisements than some of the other (equally interesting) campaigns.

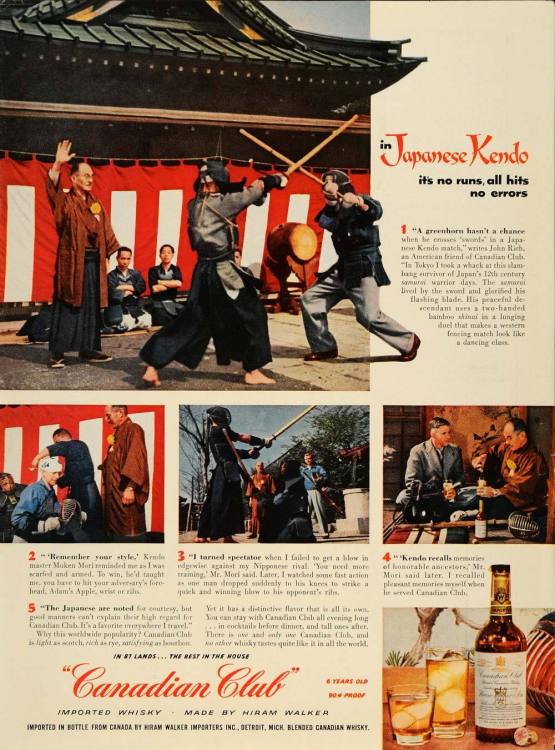

Titled “In Japanese Kendo its no runs, all hits and no errors” the advertisement tells the story of traveler who comes to Japan and, after a brief period of instruction, joins a kendo tournament. Readers are informed:

“A greenhorn hasn’t a chance when he crosses ‘swords’ in a Japanese Kendo match,” writes John Rich, an American friend of Canadian Club “In Tokyo I took a whack at this slam-bang survivor of Japan’s 12thcentury samurai warrior days. The Samurai lived by the sword and glorified his flashing blade. His peaceful descendant uses a two-handed bamboo shinai in a lunging duel that makes Western fencing look like a dancing class.”

Predictably, things go badly for Mr. Rich who is immediately eliminated without being able to get a blow in against his first opponent. His instructor informs him that he “needs more training.” But its ok, because even in an environment as exotic as this, one can still enjoy Canadian Club whisky with your fellow adventurers. Interestingly, the advertisement places Mori Sensei within the category of fellow travelers when he opens a bottle from his personal reserves. Thus, a community is formed between the jet setting adventurer and the bearer of primitive wisdom through their shared admiration for the same popular brand.

So what is the Ethos of a kendo tournament, at least according to a 1955 alcohol advertisement? It is challenging and painful. But is it primitive? Is it savage?

Historians of the Japanese martial arts can easily inform us that Kendo is basically a product of the 19thand early 20thcenturies. Yet this advertisement repeatedly equates it with the world of the samurai, thus suggests that something medieval lives on in Japan. According to mythmakers in both East and West, this is a defining feature of Japanese culture. So clearly there is a type of “primitivism” here.

Nor does one need to look far for the savagery. It is interesting to think about what sorts of practices we don’t see in these advertisements. I have never seen a Canadian Club story on judo, Mongolian wrestling or professional wrestling. Not all of these adds focus on combat, the jet setter had many adventures to consume. Yet when the martial arts did appear, they inevitably involved weapons. I suspect this is not a coincidence.

Paul Bowman meditated on the meaning of these sorts of issues in his 2016 volume Mythologies of Martial Arts. While those of us within the traditional martial arts think nothing of picking up a stick, training knife or sword, he sought to remind us that to most outsiders, such activities lay on a scale somewhere between “deranged” on one end and “demented” on the other. While one might argue for the need for “practical self-defense,” it is a self-evident fact few people carry swords in the current era and even fewer are attacked with them while walking through sketchy parking garages. There is just very little rational justification for this sort of behavior. Most of who engage in regular weapons practice can speak at length about why we find these practices rewarding, or how they help to connect us with the past. But all of that rests on a type of connoisseurship that most people would find mystifying. For them, an individual who plays with swords has either seen too many ninja movies or is simply asking for trouble. Playing with weapons (as opposed to more responsible pursuit like jogging, or even cardo kick-boxing) is almost the definition of “savage.”

But what about an entire society that plays with swords? What if one has been told, rightly or wrongly, that this is a core social value? It is that very disjoint with modernity that would make such a group a target for the desires of modern primitivism. The problem with the Chinese (and hence the Chinese martial arts) was not that they won or lost any given war. Rather, it was the (entirely correct) perception that the Chinese people did not valorize violence. Despite all of the critiques that were directed at their “backward state” and “failure to modernize” in the 1920s-1930s, their pacific nature was seen as a positive value widely shared with the West (indeed, it was a point of emphasis in WWII propaganda films). Ironically, that similarity would serve to make Chinese boxing less appealing to the sorts of individuals who consumer Canadian Club whisky, or at least its advertisement. Nor did the actual performance of real Japanese troops on specific battlefields determine the desirability of their martial arts. It was the image of cultural essentialism (carefully constructed by opinion makers in both Japan and the West), which made kendo desirable because of its “primitive nature,” not despite it.

Seen in this light, the early global spread of the Japanese arts makes more sense. What had once been a modernist and nationalist project could play a different role in the post-war American landscape. These arts promised a type of self-transformation that placed them in close proximity to the currents of modern primitivism. While the Tiki bar appealed to those who sought temporary release from the strictures of progressive modernism, the martial arts spoke to those who sought a different sort of paradise. Theirs was an Eden to be found in the wisdom of “primitive” societies and the search for the savage within.

oOo

If you enjoyed this essay you might also want to read: The Tao of Tom and Jerry: Krug on the Appropriation of the Asian Martial Arts in Western Culture

oOo