Dong Jhy and J. A. Mangan. 2018. “Japanese Cultural Imperialism in Taiwan: Judo as an Instrument of Colonial Conditioning.” in Mangan, Horton, Ren and Ok (eds.) Japanese Imperialism: Politics and Sport in East Asia – Rejection, Resentment and Revanchism. Palgrave Macmillian.

Introduction

I have been looking for comparative sources to enrich my overall understanding of China’s use of martial arts-themed public diplomacy strategies in the 20th and 21st centuries. These other cases take a variety of forms. Much of this material has proved to be quite interesting. I am slowly working my way through a volume on the history of table tennis, and the surprising role it assumed in Cold War era high stakes diplomacy. Indeed, it is not a coincidence that the PRC first began to send touring groups of Wushu athletes to the West during the era of “Ping Pong Diplomacy.” It is always helpful to be able to place developments in realm of the martial arts within a larger social and political context.

Alternatively, one can conduct a comparative study by holding the martial arts constant, and looking for other instances in which they played a critical role in a diplomatic or political process. This is actually surprisingly easy to do as many East and South East Asian countries have turned to local hand combat traditions when attempting to exercise “soft power” on the international stage. While Chinese efforts to promote Wushu may be the most visible of these campaigns at the moment, it falls within a long tradition that began with Japanese attempts to create a positive image through the global spread of Judo, and culminated with Korea’s successful bid to globalize Taekwondo in the 1970s and 1980s. Even minor powers such as Thailand, the Philippines and Indonesia have sought to leverage their martial arts and combat sports in the promotion of both tourism and national brand building campaigns.

Still, as J. A. Manga et. al. would quickly remind us, this tendency of connecting political and athletic ambition is not unique to East Asia. A quick survey of European literature during the 19thcentury suggests that the West’s imperial ambitions often found expression in, and were consciously cultivated through, the development of school sports and gymnastics programs. Such endeavors could produce the sorts of healthy bodies and disciplined spirits that the era’s militaries and civil services both required.

This tendency was developed to a greater degree on the playing fields of the UK’s public schools than one might expect. It was there that games like cricket, or the training for track and field events, came to be seen as the crucible which shaped the soul of the nation. Given the extraordinary reach of the British Empire, this ideological and rhetorical turn would have profound effects on the development of global culture. The UK exported not just technology and free trade, but also an entire culture of international sporting competition which has subsequently been taken up almost everywhere in the world.

In the introduction to this volume Mangan illustrates, at some length, how the questions of sporting competition and empire have never really been as separate as they might at first appear. No power, no matter how hegemonic, can afford the economic and military cost of ruling an empire through sheer force of arms. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that such holdings often prove so costly that alternative modes of administrations are urgently needed. Perhaps the most common of these is an attempt to instill a sense of cultural desire within the colonies for the type of life that the metropole can offer. Once the norms, education and philosophies of the center come to be desired within the peripheries, the cost of administering one’s empire drops dramatically. When individuals in the colonies consciously style themselves as British subjects, and attempt to succeed within the economic, social and cultural frameworks that the empire has established, it suddenly becomes possible for a small island nation to rule vast portions of the globe. And the spread of games like cricket and football are an important part of this fundamental re-ordering of cultural desire at the individual level.

Nothing about this logic is exclusively tied to the British Empire. Indeed, as they were building their influence throughout the region another island nation and would be naval empire carefully studied these strategies. When Japan began to assemble their own co-prosperity sphere they copied many of the lessons of other colonial empires, but added their own unique twist. In an attempt to unify their newly seized territories they too took a strong interest in athletic endeavors, promoting some activities and banning others. And, of course, they introduce Judo and Kendo to schools throughout the region as a central aspect of their wider strategy to pacify occupied territories by spreading Japanese norms and values.

As any good social scientist can tell you, even small differences in the way that a policy is implemented can have huge effect on eventual outcomes. Mangan’s introduction to this edited volume begins with an interesting question. In their time both the British and Japanese imperial influence in Asia were destructive and much resented. Likewise, the sports that both powers introduced (football and Judo) are still widely played and have now taken on distinctly national (and at times even revanchist) characteristics. Yet while the memory of British occupation often causes consternation, it is nothing compared to fury that can be unleashed by discussions of Japanese imperialism. Why is this?

This anger has many sources, not the least of which was flagrant human rights violations throughout the Second World War. Yet the authors of this volume also suggest that the Japanese approach to empire building, specifically with regard to athletics and the martial arts in the pre-war period, became a source of major resentment in areas like Korea and Taiwan. Whereas the British had attempted to use their mastery of the athletic realm to create the sort of cultural desire that lays at the heart of “soft power,” the Japanese vacillated between policies which sought to promote Judo as a means of winning “hearts and minds” in some time periods, and mandating its practice as a tool of militarism and cultural genocide (all backed by a repressive state apparatus) in others. Or to use Joseph Nye’s paradigm, they sought to bring the athletic practices within the realm of “hard power.” The results of this policy were mixed in some areas (Taiwan) and simply disastrous in others (Korea). But the very different approach of the Japanese to the question of promoting martial practice abroad, compared to either the British in the 19thcentury, or attempts to establish Wushu as a universal Olympic sport today, suggests all of this might make for a compelling comparative case.

Bringing Judo to Taiwan

Any number of chapters in this edited volume have interesting things to say on this topic. But for the sake of brevity I would like to narrow the focus of my discussion to the political uses of Judo in the occupation of Taiwan between 1895 and 1945. Dong Jhy and J. A. Mangan provide what is the most extensive discussion of this topic that I have yet seen in a paper titled “Japanese Cultural Imperialism in Taiwan: Judo as an Instrument of Colonial Conditioning.” By way of quick introduction, I would like to recommend it to anyone who is interested in the complex relationships between the martial arts and imperialism, or even the formation of political identities through martial practice. This brief chapter provides a focused overview of Japan’s problematic introduction of Judo into Taiwan, and the role of martial artists in furthering the process of both colonization and modernization. Indeed, this discussion will quickly disabuse readers of the notion that all outcomes of martial practice are positive, or that these practices are somehow apolitical by nature.

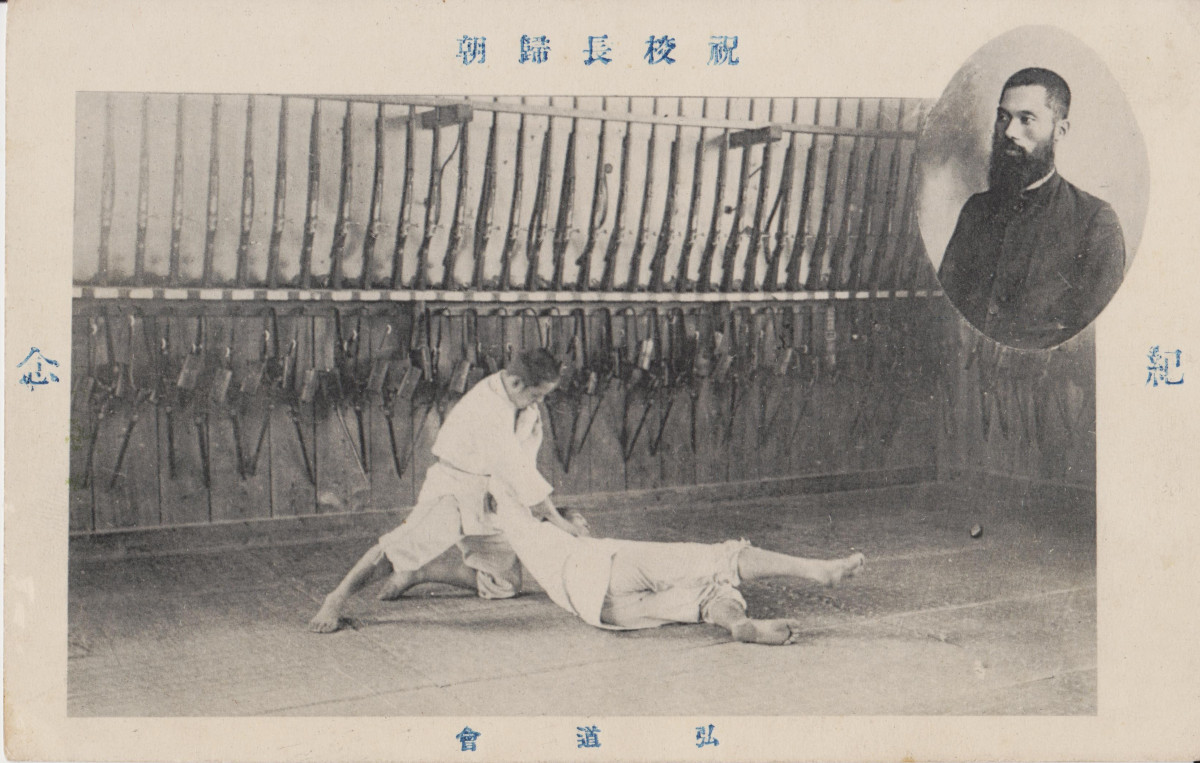

After its 1894 defeat in the first Sino-Japanese War the Qing Government was forced to secede the island of Taiwan to the increasingly powerful Japanese state. As the authors of the article make clear, Judo arrived soon after the formal handover in 1895. Of course, that same year saw the creation of the Dai Nippon Butokukai in Japan. This organization, dedicated to the promotion of the Japanese martial arts in service of the state and the Royal family, would forge a close relationship with the state’s Interior Ministry and police forces. These same officers would play a critical role in seeding the practice of Judo (as well as Kendo) in Korea when they were transferred there as part of the colonial government.

Indeed, by 1900 the Butokukai would begin to open its own branches in Taiwan. Much as in Japan, local officials and police officers took the lead in raising funds to construct regional training centers. These buildings became the locations for instruction and tournaments, all of which served to extend Japan’s cultural influence in the region. Just as importantly, they would eventually facilitate martial arts themed “good will” travel and exchanges between Taiwan and Japan.

Educational reform was one of the first major projects undertaken by the new colonial government and in 1898 they went about regulating the sorts of physical education that Taiwanese children should receive. In addition to promoting public health the new “gymnasium” classes were designed to both introduce children to a variety of “Japanized” sports as well as to inculcate them with the proper patriotic values. Mandated activities included marching with Japanese flags, singing Japanese songs, learning the Japanese national anthem and developing “Japanese” norms such as team spirit and discipline.

Still, a careful reading of the author’s timeline suggests that in this earliest period most Judo practice occurred on a purely voluntary basis with local police officers (who were required to practice as part of their professional certification) acting as instructors. They note that in this initial phase of practice the introduction of the martial arts were seen mostly as a tool to build a common community and “win hearts and minds.” In that sense the political theory of martial practice remained within the realm of soft power.

While Taiwan was one of the Japan’s longest held territories, and its programs for subjugating the people would ultimately have some success, the colonial government suffered several violent early attacks. Following a number of uprisings in 1915 the Japanese government responded by increasing its policy of promoting Judo classes as a form of “recreational distraction.” But again, at this early point almost all of the instructors remained either Japanese police officers or guest teachers from Japan. Because of the long length of time needed to establish strong schools and to train competitive athletes, many of the “Taiwanese” competitors who appeared in Japanese contests during this period were actually Japanese police officers stationed on the Island. That pattern would quickly begin to change as the practice grew more firmly established.

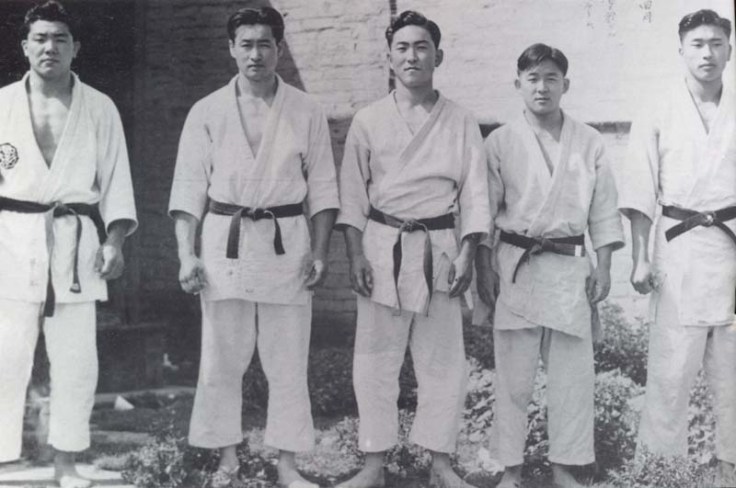

Between 1918 and 1920 (and largely in response to the spread of the Wilsonian ideal of the self-determination after WWI) the Japanese government in Taiwan adopted the policy of “gradualism and separatism.” This would have a major impact on how the martial arts were practiced. In essence, the occupying Japanese force decided that the best way to head off localized calls for “self-determination” was to rapidly accelerate the trends towards cultural assimilation that had already been established in their social and educational policies. Both individuals and groups were pressured to see themselves exclusively as Japanese subjects, and those who resisted came under increasing sanction. For the Taiwanese middle class, the practice of Judo quickly became a sign of the acceptance of this Japanese cultural identity and an important means to get ahead in (Japanese controlled) local society. Judo was seen by the government as a tool by which the Taiwanese population could be transformed into an essential (if forever unequal) aspect of the Japanese body politic.

The formal advent of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 caused another revaluation of Japan’s martial arts policy in the region. Whereas prior policies had vacillated between attempts to regulate activity, and the more traditional use the martial arts as a way of building an internalized desire for Japanese identity, the die was now cast. For the remainder of its occupation the colonial government would seek only to advance the “Japanization Movement.”

As the need for military recruits and tax revenues grew, the colonial government sought to legislate a highly restrictive vision of cultural assimilation. The use of the Chinese written language, the study of Chinese history or literature and the wearing of Chinese dress were all prohibited. Chinese religious temples and festivals were banned. In their place the government instituted a new brand of State Shinto. Meanwhile Chinese customs were to be replaced with Japanese modes of dress, membership in imperial organization and even the forced adaptation of the Japanese language. In essence the goal of these programs was to extinguish the indigenous content of Taiwanese identity, replacing it politically docile (yet physically very fit) Japanese subjects.

Once again, the Japanese martial arts were called upon to play a critical role in this national reeducation program. Training in both Kendo and Judo became mandatory for all male students with the goal of instilling the “Bushido spirit.” This would be critical as large numbers of Taiwanese citizens would soon find themselves serving in the Imperial military. Indeed, the authors suggest that an awareness of shared rituals of martial practice was critical to the process of instilling a shared sense of “Japanese identity” not just at home, but within the colonies as well.

Imported martial practices may play an especially insidious role within a colonial context. According to the authors, Frantz Fanon noted that individuals often internalize a unique sense of self-hatred which causes them to seek to shed those aspects of themselves (from skin color, to lifestyle, culture and mode of education) that mark them as colonial subjects. While Joseph Nye never seems to have considered this issue, we can actually understand Fanon’s self-loathing as the very real negative aspect of the cultural desire for the other that defines soft power.

I am not convinced that in the long-run the abuse of soft power is any more humane than its military or economic cousins. As Fanon notes, once the colonizer disappears this cultural inferiority complex can remain and maintain the institutions of hegemony long after one would have assumed that they should have collapsed (also see Robert Keohane,After Hegemony). The martial arts come into this story as these are systems that can be mastered by “outsiders”. They can thus be seen as confering a sort of honorary status on their practitioners, in this case signaling the perfection of one set of desired traits (the Budo values). And by offering this possibility of individual escape and redemption, the martial arts as a tool of colonial subjugation become ever more engrained within local society.

It is important to remember that long after the Japanese were forced to withdraw from the region, their martial arts remain. Judo is still quite popular in Taiwan. And Korea is probably the only country in the world capable of routinely fielding Kendo teams that can match the Japanese. In their current forms these arts have been (once again) reimagined and reconfigured. What was once a tool of national oppression is now understood as an aspect of a more positive national pride. Yet as the authors note, when Taiwanese and Japanese (or Korean and Japanese) martial artists meet, the sudden eruption of revanchist emotions suggest just how deep the scars of imperialism run, and the degree to which these arts were implicated in the construction and maintenance of Japan’s short-lived empire.

Conclusion

No chapter, especially one as brief as this, is without its limitations. Given the importance of the subject matter one wishes that Dong Jhy and J. A. Mangan would have been able to bring more primary source material into their discussion. For instance, I liked the comparison of overwrought writing on school sports, produced in the UK during leadup to WWI, contrasted with the equally romantic verses on the nobility of military self-sacrifice, which pepper Mangan’s introduction to this volume. Those quotes and sources really grounded the larger theoretical argument in a specific time and place.

Sadly, similarly specific sources tend to be missing from the later discussion of the Taiwanese case. In Martial Arts and the Body Politic in Meiji Japan, Denis Gainty drew on a wide range of statements by political leaders, reports in the local press, and articles in various martial arts publications to illustrate the ways in which martial artists used their agency (and practice) to gain influence in Meiji Japan. It would have been nice to see similar statements from martial arts societies or colonial leaders who seemed to be carrying out similar (though not identical) policies in Taiwan. The authors provide what appears to be a very credible reading of the historical record. Yet without more specific statements grounding all of this within the lives or careers of specific martial artists, it is difficult to know how much weight their reconstruction can really bear. I fully expect this sort of material is out there. The Butokukai seems to have liked nothing so much as a good newsletter and seeing its events reported in local newspaper. But bringing it to the fore may be helpful.

Doing so might also shed light on one of the critical questions to arise out of Gainty’s work. It is one thing to observe the vast sweep of a historical process. That is basically what the authors have given us with their history of Judo in Taiwan. And it is certainly important to see the ways that global trends (such as the spread of Wilson’s self-determination in 1918-1920) have shaped events. Yet where did the actual causal variable lay? How much of this outcome was really due to the structural considerations of colonial management, or global politics? Alternatively, what role did the agency of Japanese martial arts instructors, and later their Taiwanese disciples, play in promoting and maintaining these colonial systems?

Perhaps that would be a difficult subject to open up. It is clear that the Japanese martial arts had a very mixed legacy in Taiwan during the first half of the 20thcentury, and it is impossible to discuss agency without also touching on the concept of individual and institutional accountability. Yet if we really want to understand how the martial arts functioned within various political contexts (some innocuous and others more sinister) I don’t think we can afford to ignore this more granular level of investigation. After all, many individuals gravitate toward the martial arts precisely because they seek a sense of personal empowerment. Political studies of the Japanese martial arts, such as the one provided here, as well as Gainty’s prior volume, suggest that this aspiration may not have been entirely misplaced. As such questions remain as to whether these practices will embolden or reign-in our worst impulses. One would hope for the later, but the historical record suggests that there are no guarantees.

oOo

If you enjoyed this post you might also want to read: Butterfly Swords and Long Poles: A Glimpse into Singapore’s 19th Century Martial Landscape

oOo