This is the time of year when it is only natural to pause and reflect on where we have been and what may be coming next. 2018 has been a busy year in the Chinese martial arts. Progress has been in made in certain areas, while suggestions of trouble have arisen in others. Lets explore all of this together as we count down the top ten news stories of the last year. As always, if you spotted a trend or article that you think should have made this list, please feel free to leave a link in the comments below!

10. The first story on our list reflects one of my favorite themes (and research areas). Namely 2018 saw an expansion in the Chinese government’s efforts to harness its traditional martial arts as a tool of cultural and public diplomacy. Confucius Institutes around the world have a mandate to hold various sorts of cultural education events, and if you live near one in North America or Western Europe it is not that difficult to find a martial arts themed event once or twice a year. These efforts pale in comparison to the resources being invested in cultural exchange and education programs in Africa (where China has made substantial investments and is eager to maintain a positive public image) and in other regions affected by the “Belt and Road Initiative.” As I reviewed the last year’s news it seemed that we were hearing more about these sorts of efforts in South and Central Asia. This story, from back in July, nicely illustrates these trends as it discusses efforts to expand the profile of the Chinese martial arts in Nepal.

9. In a very real sense we are the product of our identities. They create us and impart a sense of purpose and meaning in our lives. Yet no identity is perfectly stable. These things are constantly shifting, slipping and being renegotiated as their relationship with society changes. As such, identity can be a source of anxiety, though people will go to remarkable lengths to suppress these feelings. Still, 2018 seems to have been a year when anxiety in the TCMA boiled to surface and entered into a number of (seemingly) unrelated discussions.

Certainly the ongoing trend of traditional “masters” being pummeled by journeyman MMA fighters on social media has helped to crystalize this. But it can be seen in other places as well. For instance, this account of a “Chinese Cultural Night” at a local University caught my attention as it argued that the traditional martial arts were a critical aspect of Asian American identity.

Yet Asian American media critics are increasingly reserving their praise for projects that distance the Asian American community from what they see as limiting activities and lazy media troupes. Indeed, on the media front 2018 will certainly be remembered as the year of “Crazy Rich Asians” rather than anything martial arts related. The value and place of these activities within the constellation of ideas, representations and practices that collectively comprise “Asian American Identity” seems to be up for explicit renegotiation.

A different, and more official, version of this debate seems to have emerged among certain Chinese policy makers. As our first story noted, the Chinese government has long sought to harness global interest in the martial arts, cooking and other traditional practices as a “soft power” resource in international politics. Yet another group of officials is becoming concerned that these self-Orientalizing strategies will backfire in the long run. They worry that China is not doing enough to showcase itself as a rich, technologically advanced and urban society. Individuals who travel to China may be disappointed when they discover a wonderland of modern materialism rather the romantic haven of “traditional” culture that they imagined. In any case, who is to say that this more realistic image of Chinese culture would not appeal to an ever greater segment of the world’s population (specifically, the sorts of people who enjoy scenes of rapid economic development, followed by the rise of soaring glass and steel skylines). Is it a problem that the identity which China seeks to cultivate on the world stage does not reflect the values and aspirations of many of its citizens? It will be interesting to see where this debate goes in 2019.

8. Xu Xiadong topped the 2017 news list, and he succeeded in making waves in 2018 as well. I had a particular fondness for this article which appeared Bloody Elbow back in April. It struck me as interesting on two counts. Its title, “MMA fighters batter Wing Chun Masters in China”, was a masterpiece of aspirational misstatement. A more accurate title would have read: “MMA (journeyman trainer) batters (unknown) Wing Chun (practitioner) in Japan.” Yeah, that is better.

Beyond that, this story, and others like it, capture so much of the anxiety that surrounds the Chinese martial arts. Xu has gotten in trouble with the government as they view his antics as devaluing China’s traditional culture and “humiliating the nation” (no matter how much he protests to the contrary). And the press coverage of Xu’s activities really frames an entire group of other stories chronicling the rise of MMA, Muay Thai and BBJ in China as activities to be taken up by regular citizens rather than just professional fighters (which is where Sanda and Olympic Judo had largely remained). My favorite of those pieces was the New York Times article titled “The First Rule of Chinese Fight Club: No Karaoke.” It provides a nice profile of a local “fight club,” inspired both by the founder’s love of the movie, and the growing popularity of Western combat sports in China. It discusses the legal and administrative hurdles that such a business faces, and in so doing gives a nice glimpse into the social anxieties that still surround the martial arts. Here is a quote to whet your appetite:

“…boxing, mixed martial arts and other high-energy fighting forms have been enjoying a minor boom in China in recent years. Gyms and audiences have multiplied across the country. Precise numbers are hard to come by, but one fan group estimates that the number of clubs had reached 8,300 in 2016, up from 2,700 in 2008.

Even so, commercial fight venues that draw a broader audience are rare. And Chengdu, with its zestful night life and hipster scene, seemed as good a place as any to try opening one. Yet even here the club has struggled to balance between being cool enough to draw customers and respectable enough to keep the inspectors at bay.

In a former venue, the fight club had to fend off complaints from the police, who deemed the weekly bouts undesirable, if not illegal. The authorities cut off their power and water late last year, Mr. Shi and Mr. Wang said. Tensions had also grown when a national controversy erupted last April after Xu Xiaodong, a mixed martial arts fighter, challenged masters of China’s gentler traditional martial arts to fight and flattened one of them in about 10 seconds.

Mr. Xu may have won that fight hands down, but the episode brought bad publicity for new martial arts in China.”

7. The government’s involvement with Xu’s various challenge fights should inspire students of martial arts studies to critically reflect on the various intersections of politics and Kung Fu. Indeed, the second half of 2018 saw a number of stories in which the Chinese government explicitly demanded a greater degree of loyalty from the nation’s institutions of traditional cultural.

The Shaolin Temple, in its double capacity as both a religious institution and center for martial arts training, found itself at the center of this controversy. Seeking to get ahead of new government policy directives designed to limit the independence of Chinese religious movements from the state and Communist Party, the temple’s leadership decided to take a much more visible and proactive role in promoting “patriotism” (rather than simply Buddhism) in the monks’ public performance. This is actually a somewhat nuanced topic as Chinese Buddhist monasteries have never been truly independent of the state and Shaolin, in particular, already carries a patriotic reputation. Still, the move has inspired some controversy and much discussion. A good overview of all this can be found in the South China Morning Post article titled: “Red flag for Buddhists? Shaolin Temple ‘takes the lead’ in Chinese patriotism push.” Here is a sample of the sort of pushback that has been encountered:

Tsui Chung-hui, of the University of Hong Kong’s Centre of Buddhist Studies, said Buddhist scripture already required its followers to respect the state.

“The government does not need to take pains to promote [this] and monasteries also do not need to pander to politics,” Tsui said on Tuesday. “They should let monks dedicate themselves to Buddhism and not waste their time performing various political propaganda activities.”

China has recently come under the spotlight for its efforts to clamp down on minority religions including Islam and Christianity, which it associates with foreign influence or ethnic separatism. Mosques and churches flying the national flag have become an increasingly common sight in China amid the crackdown.

6. When thinking about the Chinese martial arts and politics it would be a mistake to focus solely on the question of national identities. These systems are also invoked as part of efforts to define and shore up a wide variety of local and regional structures. This is something that we can see throughout the realm of the traditional Asian martial arts. Still, when reviewing media coverage of these events I noted that “Southern” arts (and cities showed up) with a fair degree of frequency. These articles are so interesting to me that its hard to pick just one. Over the course of the last year we saw lots of good news coverage of Wing Chun in Hong Kong, exhibitions on the Hakka arts, and a really nice piece on the rebirth of Foshan’s Choy Li Fut in the 1990s. But if forced to choose I might suggest taking a look at this piece on White Crane in Taipei. I liked the way that it explicitly engaged with the discourse linking local martial arts practice with regional prestige/identity. Note the following quote:

Every Asian nation and culture around Taiwan has laid claim to a signature martial art, such as taichi, wing chun, karate, taekwondo, Muay Thai and escrima, [Lin] said.

“It is a shame that Taiwan does not have a representative martial art,” he said. “I want to leave behind something for the nation. I have vowed that I will travel to make the feeding crane style thrive all over the world,” he said.

5. Anthony Bourdain’s death earlier this year inspired a torrent of press coverage. Interestingly, some of it focused on both the famed chef’s prior drug use and relationship with the martial arts. While not directly related to the traditional Chinese martial arts (Bourdain was an avid BJJ student), his passing did reignite interest in the use of all sorts of martial arts training to treat (and support) individuals recovering from addiction. I addressed the discursive relationship between Bourdain’s celebrity, addiction recovery and martial arts practice here. And much of the subsequent media discussion focused on programs attempting to use Taijiquan (rather than BJJ) in institutional settings.

4. Our collection of top stories in 2017 discussed some of the ways that the “Me Too” movement manifested itself within the martial arts community. 2018 was not without some disturbing new revelations of its own. But even more common was a different sort of account settling, one in which female martial arts pioneers were acknowledged for their accomplishments. The San Francisco Chronicle ran a great piece on Cheng Pei-Pei (probably the first female martial arts star) who was honored at CAAMFest. It has a number of good quotes on the golden age of Hong Kong film as well as the development of Cheng’s career. And it all started with her epic first film, “Come Drink With Me.”

From the moment she entered that inn and took a table in the middle of the room with steely confidence amid dozens of leering men — then dispatched them in an epic fight with a fury unseen in cinema up to that point, 19-year-old Cheng Pei-Pei was a star.

The year was 1966, and “Come Drink With Me,” directed by the great King Hu, was the first major martial arts movie to have a woman as the central action star, paving the way for Michelle Yeoh, Zhang Ziyi and many others. And this was 13 years before Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley character in “Alien” broke ground in Hollywood as an action heroine.

Other stories focused on the up and coming female martial artists. The rapid growth of the MMA scene in China has led to the rise of a new generation of female fighters, and reporters have been quick to record and promote their stories.

3. It seems that every year has that one story that just won’t die. Somewhat improbably, 2018’s champion would have to be “Kung Fu Bull Fighting.” If you have never heard of this “ancient” practice before, don’t worry, you are not alone. Bull wrestling was first registered as an ethnic martial art (attributed to the Hui people) in 2008. More recently practiconers in Zhejiang have taken to the practice in an attempt to create a local tourist attraction, capturing a slice of China’s lucrative domestic tourism market. And its hard to blame them. The massive success of places like Chen Village and the Shaolin Temple ensures that local officials throughout China are always on the lookout for raw material that can be turned into the next martial arts pilgrimage destination.

Still, the practice of Kung Fu bullfighting (which first hit the English language press in September of this year) feels different. While many Chinese language books on the martial arts begin with a boilerplate paragraph explaining that these fighting systems were invented in the ancient past to defend the people from “wild animals,” I don’t think I have ever seen a modern “martial art” system that claimed to take animals as their primary opponent. While it would be easy to look at this story in terms of (transparently) “invented traditions” and the demands of local tourism markets, I suspect that there is more going on here. The constant comparisons to Spanish bull fighting in these articles suggests an exercise in both gender and national identity construction. On the other hand, given all of the news about the Chinese martial arts (movies, sporting events, kung fu diplomacy, etc…) that is produced every month, one has to wonder why this story has captured the English language press to the degree that it has? Clearly there is a healthy dose of Orientalism going on here. But what specifically do readers imagine that they are learning about Chinese culture as they immerse themselves within the world of “ancient” Chinese bullfighting? What does this suggest about the ways that China continues to be imagined in the West? The strange endurance of this story reminds us that even the least serious practice can inspire important questions.

2. There is no better known figure within the Chinese martial arts than Bruce Lee. Indeed, he is probably the most well-known martial arts figure of all time. Still, even by Lee’s elevated standard, 2018 was a good year. Anniversaries aside, much of that credit must go to the well known author Matthew Polly who finally released his long anticipated (and extensively researched) biography. I don’t think its an exaggeration to say that this Polly’s effort is destined to be remembered as the definitive Bruce Lee biography.

Just as interesting as the book itself was the media’s response to it. While the tabloids tended to dwell on Polly’s more lurid revelations, the book was reviewed, discussed and meditated upon in a surprisingly wide variety of print and televised outlets. Pretty much every major newspaper and magazine weighed in on Polly’s book, some more than once. Discussions of this work dominated the Chinese martial arts headlines for months, testifying to Lee’s enduring charisma. Lee even got his own academic conference earlier this year (at which Polly made an appearance)! All in all, 2018 was a good year for the Bruce Lee legacy, and it suggests that his image continues to shape the way that the public perceives the Chinese martial arts.

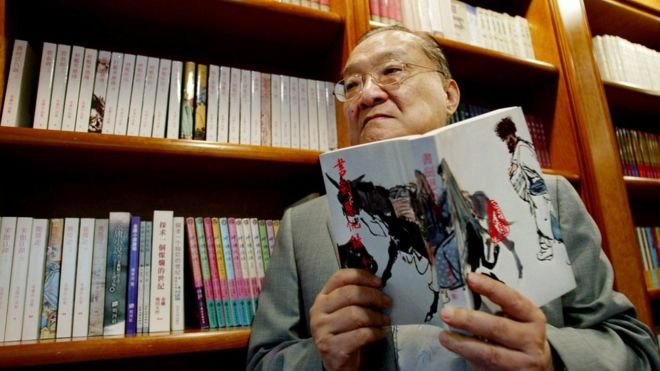

1. This brings us to the top news story of 2018, the passing of Louis Cha, also known to his fans as Jin Yong. Indeed, coverage of his achievements began relatively early in the year with the announcement of new graphic novels based on his work, and the release of an important English language translation of Legend of Condor Heroes. While Cha is the best selling modern Chinese author, few of his works had found English language publishers. As such, this new translation was treated as a major publishing event which generated a large number of reviews, discussions and think pieces.

That press coverage proved to be only a primer of what was to come following the author’s death (at the age of 94) at the end of October. It seemed that every major paper and news outlet on both sides of the Pacific was eager to remember and reevaluate the fruits of a remarkable life. There was much to be said regarding Cha’s contributions as a newspaper editor and leading (and at times controversial) political figure during Hong Kong’s transition to Chinese rule.

Yet it would be impossible to overstate the importance of Cha’s Wuxia novels in the rejuvenation of Hong Kong’s post-war martial arts culture. His stories provided practices that were often publicly scorned with a degree of gravitas. They granted cathartic relief to a generation of exiled readers struggling with the sudden realization that after 1949 they would not be returning to their homes in other parts of China. Later they helped younger readers to position their own martial practice and social struggles in terms of larger cultural and historic narratives.

While Cha was never known as a martial artist, his writings helped to popularize and give social meaning to these practices. Indeed, for cultural historians of the Southern Chinese martial arts it is often necessary think in terms of the “pre” and “post” Jin Yong eras. While Cha’s passing is a tragedy, the remembrances of the last few months have highlighted his enduring contributions to the public appreciation of the Chinese martial arts.