Lawrence N. Ross. 2017. “Demi Agama, Bangsa dan Negara: Silat Martial Arts and the ‘Third Line’ in Defense of Religion, Race and the Malaysian State.” In Sophie Lemiere (eds.) Illusions of Democracy: Malaysian Politics and People. Vol. II. Strategic Information and Research Development Centre: Malaysia.

Martial Arts and Modern Politics

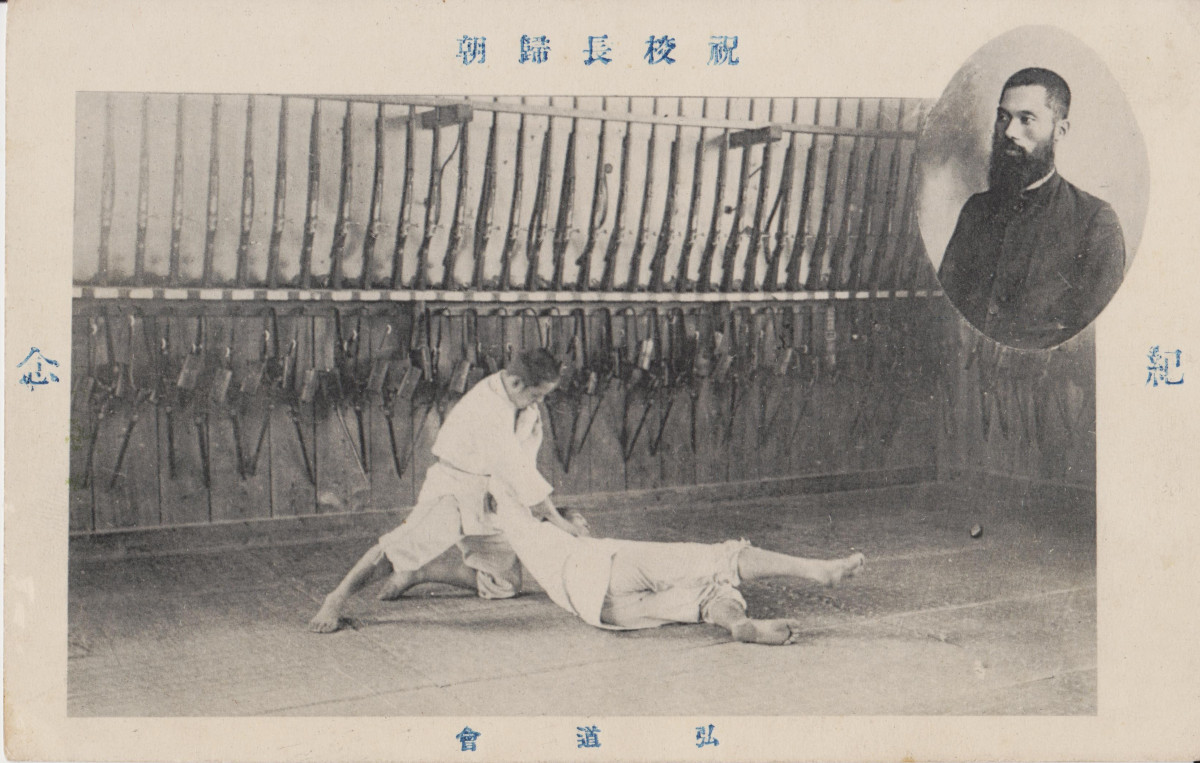

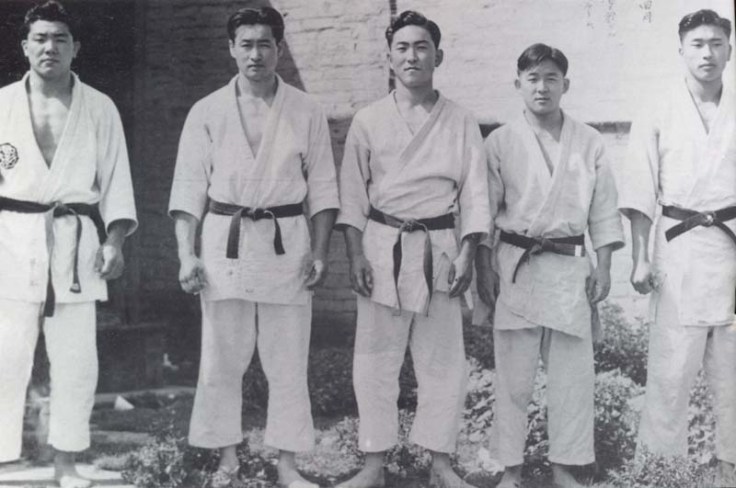

Over the last few months I have written a number of posts discussing the interplay between martial arts and politics in the early 20th century. It is not hard to look at the Japanese promotion of Judo in colonial Taiwan, or the Chinese state’s promotion of first Guoshu and then Wushu, and perceive an interplay between martial practice and political strategy. The first half of the 20th century presents students with a wide assortment of case studies, each alerting us to the role of ethno-nationalism, ideological struggle, imperialism and the nation building process in the shaping of the East Asian martial arts.

Yet is all of this only an artifact of the past? In the absence of imperial, post-colonial and national struggle, what role can the martial arts play in the modern political landscape? Can martial practices or organizations still be seen as relevant actors in the current era?

Being a political scientist by training, I spend a lot of time thinking about questions like this. Clearly, I must believe that the martial arts are relevant to both international and domestic politics or I probably wouldn’t be as interested in studying them. My current book project, looking at the interplay between China’s traditional fighting arts and its global public diplomacy strategy, is explicitly premised on the ongoing relevance of these images and practices within the transnational sphere. But what are we currently seeing in the more mundane realms of daily domestic political struggle?

While conducting a review of news reports in December of 2018, I noticed a spike in discussions of Malaysian Silat. Sadly, not all of these stories were positive. The appearance of the Silat at the Asian Games (hosted in Jakarta) had been marred with unsportsmanlike conduct by both fighters and crowd. Given the historic rivalry between Indonesia and Malaysia, more than one commentator was left to wonder whether the sport’s inclusion had actually been a good thing. Later (in November), young Silat practitioners were implicated in a violent attack on a Hindu Temple in Selangor. The incident was embarrassing and led to the Pertubuhan Silat Seni Gayong Malaysia (PSSGM) secretary-general Mariam Bujang being forced to publicly argue that the perpetrators were not actually members of that association but its defunct predecessor. One way or another, the story didn’t contribute to a positive perception of martial artist in the area.

The biggest story surfaced in December. Thousands of Silat practitioners, all wearing their official training uniforms and carrying association banners, gathered at the Federal Territories Mosque in Kuala Lumpur. Chanting “Allah is Great” they marched in protest of the government’s plan to ratify the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), a UN memorandum dating from the 1960s. This document became a lightning rod within a political landscape shaped by ethnic and religious identity. In some corners it was seen as threatening the place of Islam in the country, even though a number of other Muslim countries had ratified it. Other critics were concerned that the majority ethnic Malay population would lose certain affirmative action preferences under the new document, even though most legal scholars agreed that such programs and policy would be unaffected. Nevertheless, leaders of various Silat associations were quick to call their members out into the streets, determined to protect both Islam and the nation for the perceived global threat. These protests generated a number of stories (and some nice video footage), which quickly spread around the world.

Malaysia is no stranger to what some of my colleagues call “contentious politics.” Nor, in truth, is Silat. The leaders of some organizations have been very vocal in expressing their opposition to certain policies. In general these martial arts group have played a quieter supporting role. Yet even when they have been positioned off stage and out of the limelight, their presence has still been felt. What was unusual was to see a number of high-profile stories in quick succession, each of which centered the Silat community within these debates. So how can we better understand the role of Silat within Malaysia’s ongoing pattern of contentious (and sometimes violent) debate?

A History of Struggle

Lawrence N. Ross, a faculty member of the University of Malaya’s Department of Socio-culture and Malaya Arts, has recently authored a short article seeking to answer this very question. It draws on his extensive background as a scholar of the region, as well as the familiarity with the Silat community which he has gained as a practitioner. Ross’ essay has the unenviable task of familiarizing non-specialist readers with both the relevant aspects of Malaysian political history as well as the development of its martial arts traditions in too few pages. In reading it, I was struck by how rarely students of Martial Arts Studies are ever afforded the privilege of “hitting the ground running” when writing an essay in the same way that a political or economic historian might be. The standing assumption is always (and generally with good reason), that the average reader will be coming to these topics for the very first time. Hopefully that will change as our field grows.

Still, Ross does a very good job of introducing and contextualizing lots of information in such a way that it will be understandable to those who aren’t all that familiar with the practices that he is about to discuss. This is the sort of paper that one could easily include on an undergraduate syllabus even if the course in question was not directly focused on Malaysia. I suspect that many political science students would find the discussion to be both interesting and relevant.

Beyond a simple review of Silat as a martial art, Ross immediately underlines the degree to which the practice has emerged as a critical touchstone of debates over the nature of Malay ethnic identity, and from there to Malaysia’s national character and destiny. This discussion is grounded in a series of short historical cases in which major stages in the development of Silat’s institutional organization are reviewed and correlated to corresponding events in the life of the country.

Obviously, the May 13th Incident (when hundreds of mostly Chinese victims were killed by Malay rioters after the opposition parties made gains in the 1969 national election) plays an important role in this narrative. As Ross points out, the leaders of various martial groups have not been shy about invoking the memory of widespread anti-Chinese violence and killings in this period as they have laid out their social and political demands in more recent years. Yet the history and the nature of the interrelationship between the state, Malay society and Silat run much deeper, and are much more complex, than this single incident.

Ross places the genesis of the modern connection between Silat and the state in the immediate post-WWII era. During the power vacuum that existed between the defeat of the Japanese and the re-establishment of British rule, a Silat militia called the “The Army of the Cause of God,” arose in the southern state of Johor and basically went to war with both the Chinese Malayan Anti-Japanese Party and the Malayan Communist Party. The widespread slaughter of this period, in Ross’ view, laid the foundations for later outbreaks of anti-Chinese violence.

Another interesting case study emerges later in the 1970s with the rise of a group called Nasrul Haq. It too functioned as an ersatz Silat militia this time under the personal command of a young, highly charismatic government figure named Abdul Samad bin Idris. The group targeted impoverished or working-class youth for recruitment and was built upon a synthesis of religious fundamentalism and ethno-nationalist revivalism. However, when the political ambitions of its patrons became too threatening, the rest of the government unleashed a series of investigations and repressions that would help to further shape Silat’s relationship with the state.

Ross reviews a number of other events, including the creation of the major mainstream Silat organizations that currently dominate the art’s practice, and the rise of “oppositional Silat” in the 1980s. He also discusses the PAS’ sponsorship of generally very benign classes and community associations after their 2008 electoral victory in an effort to build trust and social capital. He noted that while these classes might be proceeded by lengthy religious sermons, in actual practice they weren’t all that different from the sorts of martial arts classes that you might find offered in community centers anywhere else in the world.

Undoubtedly my own background within International Relations (and interest in public diplomacy) shapes many of the discussions of martial arts and politics which readers will find here on Kung Fu Tea. By in large I have written about outward facing discussions where nations harness some aspect of their traditional domestic culture to affect the sorts of perceptions and political calculations that happen on the global stage. Unsurprisingly, the sorts of states that can engage in this sort of behavior (whether it is the rivalry between American and German boxers in the 1930s, Japanese Judo players in the 1920’s, or efforts to place Wushu in the Olympics today) tend to be the Great Powers within the global system.

Ross’ article shifts this discussion in important ways. His focus remains resolutely on the interaction between martial practice and the domestic political landscape. Indeed, as we review the various time periods laid out in this article, we see a practical menu of all the ways that the martial arts might become relevant to shifting domestic debates. Everything from their didactic media presence, to role in shaping community identity through physical organization is touched on.

If we were to draw just a single conclusion from this much more complex discussion, it might be that the Malaysian martial arts have been critical to the political process not because everyone practices them (indeed, most people don’t). Rather, their strength derives from their ability to build social cohesion within limited, almost factional, communities that a wide variety of political and social elites find quite useful. Indeed, they find this trait so valuable that they have been willing to support and subsidize several types of martial practice. Many Silat groups have responded in kind by supporting ruling government parties and constructing large communities dedicated to the perpetuating a certain vision of Malaysian identity. In effect this freezes in place the social groups who are winners and losers from government policy choices.

Ross is careful to note in multiple places that most Silat students are in no way connected to anything like political thuggery. They just focus on their personal studies and events in their local communities. Yet he also notes that there is a latent power within this community, as witnessed by recent demonstrations that have turned huge numbers of Silat students out onto the streets, that suggest that the art still functions a potential militia, one dedicated to certain political parties, but also to a specific understanding of Malay identity.

Conclusion

Paul Bowman, in one of our journal editorials, asks whether the martial arts, and by extension Martial Arts Studies, really matters. In many ways this was basically a rhetorical question. Having written several books and articles, organized conferences, received grants, and started journal all dedicated to the martial arts, I think we can safely assume that he believes that they matter. The real question, the one that we should engage with, is “how do they matter,” and “how can I convince other scholars/publishers/editors that they matter.”

Ross’ article struck a cord with me as it speaks succinctly to these points. The degree to which the Silat community has become publicly visible (even within the global press) in Malaysia’s contentious politics over the last few months is somewhat exceptional. The author does a good job of exposing the various ways in which martial arts groups have been present in a variety of areas, even when their effect is not necessarily evident to those outside the country. Clearly the martial arts matter if we want to understand identity or social conflict in a variety of South East Asian countries.

The Malaysian case nicely illustrates that these sorts of conversations are not just a relic of the first half of the 20thcentury. The martial arts continue to be directly implicated in not just global but also domestic political discussions around the globe. When we ignore these groups, we miss a mechanism by which preferences are created, aggregated and articulated in a variety of systems.

As always, I have certain criticisms of this article. Silat is not the only martial art practiced in Malaysia. The Chinese community has built an especially strong network of martial arts schools and associations of its own. Nor has it forgotten the events of 1969. It would have been very interesting to take a step back and look at the larger landscape, drawing parallels and contrasts with the ways that different martial arts groups have been drawn into (or shunned) political discussions.

Some unresolved tensions also remain in within Ross’ basic argument about the nature of the Silat community. Attentive readers may have even picked some of them up in my own brief summary. The overarching thesis of his argument is that the Silat community is imagined as (and at times is explicitly called upon to function as) an immense informal militia that stands ready to defend specific government actors, ideas about Islam and (most importantly) Malay ethnic identity. Indeed, Ross provides extensive quotes by various leaders of national martial arts organizations suggesting that they are very much aware of, and invested in, these responsibilities.

At the same time, Ross cautions us that most Silat students are not political agents and are just concerned with taking a class at a local community center or studying with a local village master. Undoubtedly this is true. And yet something seems to be missing from the story. Specifically, how is it that some individuals, but not others, get pulled in an activist direction? What is the actual social mechanism that draws in some schools in but insulates other sorts of communities? What are the actual boundaries of this vast national militia? And how do they shift as the politics of the day become more heated and contentious? That last question would seem to be especially important at the current moment.

Of course, none of these questions could be addressed without vastly expanding the length and complexity of the chapter that we are reviewing. In an edited volume these sorts of questions are almost never under the author’s control, so it is probably not fair to hold Ross responsible for them. As I said before, he does a remarkable job of getting a non-specialist up to speed, and that is probably enough. But I would certainly like to hear more on all of these topics. Let’s hope that Ross has a book length manuscript in the works!

oOo

If you enjoyed this review you might also want to read: Through a Lens Darkly (9): Swords, Knives and other Traditional Weapons Encountered by the Shanghai Police Department, 1925.

oOo