The Unexpected Giant

Some of the essays at Kung Fu Tea are the result of several days of careful research and thinking. This is not going to be one of those pieces.

I started out with a great topic. It was my goal to explore the stochastic progress of duanbing, a type of competitive short-weapon fencing, conducted with specific safety gear, which has been on the verge of “really taking off” within the TCMA community ever since the late 1920s. As I began to assemble some articles and descriptions of the first phase of duanbing practice in the 1930s, one name just kept coming up. In fact, I ran across so many references to this individual that I just had to find out more about him.

Sadly, he has nothing to do with Chinese fencing. But Col. Voldemar Katchorovsky did make quite an impression on anyone who met him. His colorful career suggests something about the general attitudes which shaped the development of Guoshu, as well as the types of adventurous individuals, peripatetic either by choice or circumstance, who shaped the global transmission of all martial arts (both Eastern and Western) during the 19thand 20thcentury. Lastly, his career is also a valuable reminder that duanbing did not emerge in a vacuum. It was developed at a time when both Japanese Kendo and Western foil fencing were making inroads into Chinese schools and popular culture. As I (and many others) have already noted, the development of any “local” and “traditional” practice must arise in discourse with notions such as “international” and “modern.” Katchorovsky’s writings provide us with a very specific example of how these concepts entered discussions of martial and combative pursuits in China.

Who was V. A. Katchorovsky? It is difficult to say with absolute certainty. As with many martial artists, we simply do not have a complete life story. Yet a review of period newspapers reveals two competing narratives. The first was something that Katchorovsky’s inherited. Despite his enormous height (over seven feet), and unusual profession (fencing instructor), most people saw him primarily as a refugee, a former Russian military officer displaced by the Bolshevik Revolution. Indeed, quite a few Russians refugees would eventually end up in China, and they seem to feature prominently as “threatening outsiders” in many kung fu legends. Perhaps we should not be surprised that displaced individuals (many with a military backgrounds) would end up coming into contact with China’s own martial artists.

Still, Katchorovsky’s path to China was far from direct. The first mention that I can find of him comes in the form of a short article in a local paper in New South Wales, Australia. It seems that in 1924 Katchorovsky was passing through on his way to Tahiti. Yet he was viewed as such a tragic figure that an article on his visit was necessary.

Giant Refugee

Body Guard of Murdered Czar

Melbourne, Saturday. –Penniless and physically worn, after years of intense anxiety, Artillery Colonel (W)oldemar Katchorovsky, once of the first Artillery Brigade attached to the late Czar’s Imperial Russian Life Guards, arrived in Melbourne on Wednesday. He stands over seven feet one inch high.

Having been hounded out of his country by the Bolsheviks, Katchorovsky is on his way to Tahiti, where he will join another refugee, Colonel Basil Nik[]tine. His fortune having been confiscated, he was obliged by necessity to travel steerage on the French liner Ville de Strassbourg.

Katchorovsky was one of the late Czar’s bodyguards. As a refugee in Malta with the Dowager Empress Maria Deodorovna, he learned the authentic story of the death of the Royal family.

While the Royalist Generals were organizing volunteer corps in the Caucasus and Crimea, the Czat and his family were taken prisoners to Ekaterinburg, Western Siberia. According to the Dowager Empress, his majesty was killed by the prison guard against military orders. The rest of the family, after suffering terrible humiliation, were likewise done to death.

Katchorovsky carries with him treasured photos of himself taken with members of the royal family when holidaying in Lividia Palace in the Crimea.

Northern Star(Linsmore, NSW) 16 June 1924. Page 4.

Readers should note that this piece contains no discussion to fencing, leading me to wonder whether Katchorovsky had begun to teach. Tahiti in the 1920s, while probably lovely, would not have been my first choice of location to open a new fencing salon. Beyond that, this article offers readers very few biographical details. We do not learn how old Katchorovsky was, or whether he ever had a family. Nor do we learn where he was coming from.

Like many refugees in our own era, Katchorovsky seems to have been subjected to a process of biographical flattening. His entire life is reduced to only those elements most interesting to the paper’s readers. One suspects that in the 1920s any number of White Russian refugees might have passed through the same area and inspired almost identical articles. In this discursive movement Katchorovsky, as an individual, was hollowed out and reduced to a symbol of the era’s increasingly well-developed fear of Bolshevism.

Maitre d’Armes

Whatever business Katchorovsky had in Tahiti, he seems not to have stayed long. In 1927 his name resurfaces in another newspaper in New South Wales. Then in 1930 we catch a glimpse of him in Honolulu. While most of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa was consumed with an upcoming football game against BYU, the school newspaper reported that an exhibition fencing tournament had been planned between the students of Katchorovsky and those of Cedric Wodehouse (a local instructor who had been trained in the UK). Once the preliminary matches were finished, the student body was promised an exhibition match between the two instructors. This was billed as a “real match between experts.” Without digging into more detailed local historical sources, it is difficult to say how long Katchorovsky stayed in Honolulu.

In any case, he did not put down roots. Two years later a student newspaper for the University of British Columbia (Vancouver) ran a brief notice stating that Katchorovsky had taken up residence in the area and was looking to establish a class for local university students. Any student wishing to take him up on the offer needed to hurry. By the spring of 1933 Katchorovsky would be seeking to establish a somewhat larger presence in Shanghai.

This is the period of Katchorovsky’s career that generated the most interesting paper trail. Between February 19-22 of 1933, he wrote a series of three, highly detailed, articles for The China Press. Each of these sought to explain and promote Western style fencing as a desirable type of personal exercise and competitive sport. [Readers should note that, confusingly, both the second and third articles in this series are labeled as “number two,” so it is necessary to actually check the dates of publication]. Collectively these discussions seem to announce the arrival of a more prosperous stage of Katchorovsky’s teaching career.

Readers may recall The China Press was one of Shanghai’s leading English language “treaty port” papers. While the editor of this paper was Chinese, and a virtual agent of the KMT government, the China Press prided itself on its connections to the American tradition of journalism and liberal editorial slant. The paper served three audiences. Obviously, it spoke to the needs of the expatriate English speakers in Shanghai. Yet unlike other foreign language papers, it reported extensively on Chinese political and social events. Indeed, its ostensible foreign ownership helped the paper to skirt certain censorship regulations, and it thus also appealed to educated, English reading, Chinese citizens. Lastly, the KMT tolerated papers such as this as they hoped that they would bring news of what was happening in China (unfiltered by the always hostile Japanese newswire services) to citizens in the West.

Given this complex readership, it is significant that The China Press was unrelentingly enthusiastic about all aspects of the martial arts. It seems to have published more stories on Chinese boxing (or “national boxing”) than any other treaty port paper. But it also reported on judo, kendo, boxing and fencing. One suspects that someone in the editorial office took a keen interest in martial pursuits.

Still, the degree of coverage that Katchorovsky’s thoughts on fencing received seems exceptional, even by the standards of The China Press. As I mentioned in our prior discussion of Ma Liang’s New Wushu movement, certain outlets also offered their services to government officials or important individuals who sought (for a price) to promote a project that was generally in line with a paper’s editorial policy. For a few years the China Press even seems to have run an ad hoc English language public diplomacy program for the KMT. I suspect that Katchorovsky may have entered into a similar promotional arrangement with the paper.

His first three articles, in April of 1933, were immediately followed up by another piece at the beginning of March. This article (written by a reporter) sought to both promote fencing in general and Katchorovsky’s classes more specifically. It noted that he had recently been hired by St. John’s University as a fencing instructor for the students. The paper proclaimed (probably incorrectly) that these were “the first Chinese [boys] to take up this typically European sport.” It was also noted that his experience in America demonstrated that fencing was really a sport for everyone, regardless of age or gender. A local girl’s school was also considering adding fencing classes.

Again, it is difficult to know exactly when Katchorovsky arrived in Shanghai and began teaching. But at the end of March (22nd) the China Press ran another story, probably independent of any formal advertising campaign, noting that due to the increased popularity of the sport an exhibition had been scheduled at the International Branch of the YWCA. Exactly one week later (March 30th) another unsolicited article was run reporting on the result of this social and athletic gathering. Such stories are relatively common in the pages of The China Press. Still, it seems that this event made a positive impression on the reporter. Like Hawaii, the student tournament was followed by two exhibition matches in which the various coaches and organizers demonstrated other weapons and superior techniques for the crowd.

Skimming various accounts of tournaments and exhibitions, it seems that much of the fencing in Shanghai was led by, or included, Russian refugees. Indeed, one wonders whether this was what drew Katchorovsky to the city in the first place. His own match was against Dr. Schoenfeld. Col. Minuchin, who coached many of the participants, is reported to have graduated from the Officers’ Fencing and Gymnasium School in Petrograd just before the outbreak of WWI in 1914. He had been living in Shanghai for approximately five years.

All of this publicity resulted in two photographs of Col. Katchorovsky in his role as fencing instructor. The first, published on Feb. 27th, shows a sophisticated looking individual, hair parted in the middle, sporting round glasses and a neat mustache. He holds his trademark foil and fencing mask on his lap as he seems to look beyond the camera with a pensive gaze. If the first image is serene, the second is slightly unsettling. It was taken on the day of the YWCA tournament/exhibition. Several female students sit in the front with their instructors standing behind them. Shown at his full height, Katchorovsky towers over the others. At first one guesses that the other coaches must have been sitting as well, but of course they are not.

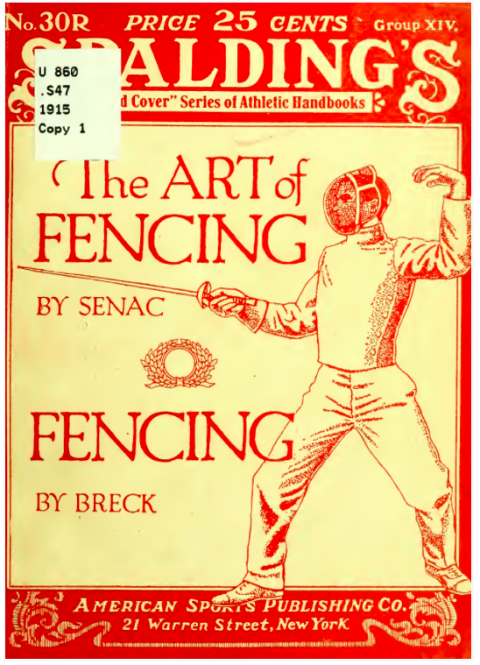

The China Press revisited fencing again on October 27th with another article by Katchorovsky. This piece quoted liberally from the Art of Fencing by Senac and Fencing by Brek in an effort to argue for the athletic, personal and somatic value of the practice. Not to be outdone, the North China Herald also ran an article by Katchorovsky on November 7th. Unfortunately, this rehashed many of his prior points without adding much new to the discussion. Still, in a remarkably short period of time Katchorovsky had written or been discussed in at least eight articles and received two photographic features.

That is a remarkable amount of press coverage for anyone in this period, let alone someone from the martial arts community. But his efforts paid off. The introduction to the October China Press article noted that Katchorovsky was currently serving as Master of Arms at both the Shanghai American School and St. John’s University, while running his own fencing academy at 73 Nanking Road.

Modernity’s Knight Errant

Given the volume of material that Katchorovsky produced, it is important to ask how he (and other instructors) sought to promote fencing in the 1920s and 1930’s. More specifically, how are the values that they sought to promote similar to, or different from, the sorts of discussions that other martial arts (especially Guoshu and Judo) were generating? One might suppose that given his military background, Katchorovsky would be something of a traditionalist when it came to the sword. He came of age in an era when there was still an expectation that officers might have to fight with their swords. And all of that seems to fit with the more tragic and orientalist ways in which the press sought to frame his life narrative.

Yet Katchorovsky was no traditionalist. One suspects that he would have had little tolerance for the sort of essentialist cultural rhetoric that followed Kendo. His understanding for the need for modernization and reform within the martial arts would have fit well within the more progressive currents of China’s own Guoshu movement. Note, for instance, the following excerpts from his discussion on the topic of traditionalism vs. modernity in his third article for The China Press, titled “Modern Fencing Reaches High Sate of Perfection.”

…There are so many people who have never given up the old-fashioned idea that fencing is an ancient art, graceful and beautiful to behold upon the stage. Many never think of fencing as competitive sport, which it really is—the fastest and most brilliant of all man to man sports in existence.

Fencing progresses like everything else. A fencing bout of two hundred years ago and a present day match have very little resemblance. Fencing today is very fast, very competitive, and a study of it gives one a deep and interesting experience in the thoughts of modern science and philosophy, such as timing, motion, space, reflex-action and counteraction, and shows one the vast differences between perception and intuition.

Suits Modern Youth

Fencing today is very modern, very athletic, very fast, sparkling and vivid, almost scientific. It should suit the modern youth to perfection. He can still keep his identity, his individuality, be a little swaggering and devil-may care, and possibly fence better for it….

Helps Eliminate Time

I know of no other sport today which has become as ultra-modern as fencing. In my opinion fencing develops such keenness and precision that it becomes far more mental than physical. A fencer finds that along with modern inventions, modern science and its fourth dimension, this sport goes a long way to eliminate more of the encumbering element of matter we call time.

To think is to set, i.e., when you think “thrust” your arm is already extended: when you think “lunge” your right foot hits the floor with pantherish agility.

It is especially true that in a hardfought bout between equals you are never conscious of your body. It has ceased to exist; that is, it is no longer the tool of the mind, but becomes the mind itself.

Ultra-Modern Thrill

You lose all consciousness of self and exist as the mental qualities of speed, precision, accuracy, distance, balance, judgement or seem to exist as life and action itself. For your time is not, and each moment of action flashes from the future into the past without the realization of its passing.

After a twenty-minute bout, whether you have won or lost, you feel that if you have not spent a second in eternity, you have least lived more vividly, more intensely during these minutes than is ordinarily lived in a week.

Thus fencing, once necessary as a means of bodily protection between the exponents of the art, has today become a new mental and physical thrill for the ultra-modern.

1933. A. Katchorovsky. “Modern Fencing Reaches High State of Perfection.” The China Press. Feb. 22 1933. Page 8.

This is one of the more interesting first-person accounts of any martial practice which I have encountered during the 1920s or 1930s. While most of Katchorovsky’s articles tend to emphasize the fully-body muscular development that fencing provides, or its utility for students seeking to lose weight, it seems clear that he was motivated by a quest for altered states of consciousness. This article provides a very detailed account of what it is like to experience a “flow state” in weapons work. Yet rather than seeing this as a universal psychological phenomenon, something that might occur in any number of activities, he supposed both that it is unique to fencing and its modern reforms. Katchorovsky even points to the achievement of personal goals and individually attained altered states of consciousness as core qualities of his “ultra-modern” martial art. Reading these passages I am left to wonder how many practitioners of combat sports in or own era might agree with him, even if they have never picked up a foil.

All of this might seem very distant from the world of Guoshu and the development of duanbing. And, in a sense, it is. Yet it must also be remembered that the great reforms of the 1920s and 1930s did not happen in a vacuum. Both Jingwu and Guoshu sought, in their own way, to appropriate and respond to the discourse of modern superiority which was projected by the Western imperialist powers. That is why the “traditional” Chinese martial arts which we practice now are, in fact, a product of modernity.

Conclusion

Of course, fencing is also modern art. Katchorovsky’s embrace (even celebration), of this fact is probably a multi-layered phenomenon. On the one hand, it may have been commercially necessary to distance fencing from its historical association with dueling if one wanted to win middle class female students. Doing so might have been more challenging than one might guess as even newspapers in China were carrying stories of duels (some carried out with sabers, others with pistols) which were still happening in France as late at the 1930s. At least some of Katchorovsky’s rhetorical efforts to carve out a space for sport fencing as a distinct modern practice, unrelated to the art’s bloody past, were probably necessary. [For a sample of what else his audience might have been reading see “Savage Duel is Fought by Paris Lawyers.” The China Press, March 10, 1935. Page 3.]

Of course, “ultra-modern” practices are by definition young, trendy and more likely to be popular with university students. Such things are also transnational and transcultural, values that he probably felt very strongly about given his constant wandering. Undoubtedly Katchorovsky reveals something of his life experience in all of this. Scientific rationalism and international community may have been things that he could ground his identity in after the nation-state and political ideology had failed him. He many even have seen these values as tools to push back against the socially dominant narrative that defined him solely as a refugee.

Modernity takes on a variety of meanings as we read these accounts of fencing’s brief flowering in Shanghai during the 1930s. Yet all of this was happening in concert with larger intellectual trends and global events. Katchorovsky is a valuable remainder of the role of marginal and displaced people in the popularization and spread of modern martial practices. Beyond that, his writings offer a particularly clear glimpse into the sorts of concepts that shaped both the development of the Guoshu movement and the modern Chinese martial arts we know today.

oOo

If you enjoyed this discussion of the the martial arts scene is Shanghai in the 1930s you might also want to read: Mixed Martial Arts in Shanghai, 1925

oOo