Are Martial Arts Political?

My friend, Paul Bowman, recently asked the rhetorical question, “Should martial arts be active or passive players in politics?” The question is rhetorical in a double sense. Paul never directly answers his own query, but instead outlines for readers of the Cardiff University School of Journalism’s blog some of the questions that we have been grappling with in the last few months. It is rhetorical in another sense because on some level it does not really matter what anyone’s answer is. One may wish to see your school have more or less political involvement, yet as a matter of basic historical fact the martial arts have often been actively involved in the major political debates of the day.

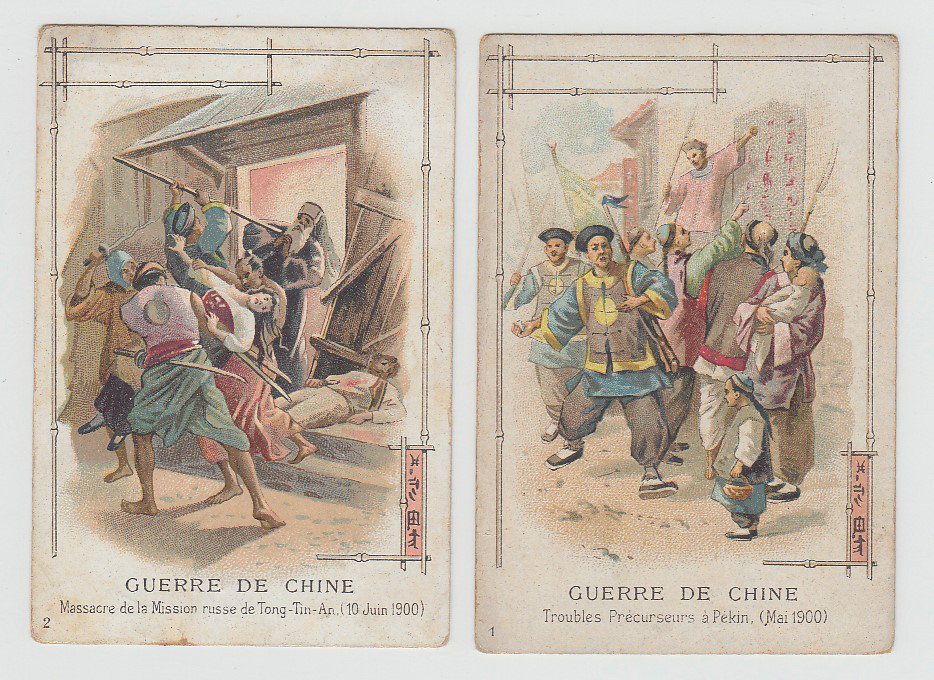

This was true in Japan in the late Meiji period, China during the Republic and Korea in second half of the 20th century. Bruce Lee was quickly adopted as a critical figure in American debates on racial equality, and Wing Chun materials produced in Germany during the 1970s and 1980s frequently opined on that country’s changing social mores. In the current era Wing Chun has again emerged as a master symbol of Cantonese culture as debates over the extent of local independence heat up in Hong Kong. And we have all been discussing the attempts of the Rise Above Movement (and other violent extremist groups) to employ the martial arts in their various organizational and recruitment efforts here in the US. Indeed, our most basic understandings of the martial arts arose in large part out of the nationalist, anti-imperialist and ideological conflicts that shaped the 20thcentury. Seen from a macro-historical perspective, how could we believe that the martial arts are anything other than overtly political?

Yet on a day to day level most martial art training doesn’t seem to have anything to do with politics. Obviously, there are a few exceptions. Some capoeira schools might emphasize social equality in their selection of music or community activities. Likewise, the alt-right fight clubs that have been so much in the news seem to make a point of framing their activities through an overtly political lens. But in my (admittedly limited) experiences, these situations are the outliers, and not the norm. The challenges that most Western students face in the training hall are overwhelmingly personal and physical in nature. The frustration, pain and elation of training seem to fall on everyone, irrespective of ideology. It is these very personal experiences that dominate our practice.

Yet the personal has a way of becoming political. As I have previously noted, embodied experience, while engulfing in the moment, is never self-interpreting. Nor are identities self-constructing. Each of us receives a wide range of social, familial, economic, cultural and political cues as we attempt to sort out “what just happened” and “what sort of person am I.” If we were a student doing Kendo katas in the 1930s, the answer to that last question was quite clear. Through diligent training education officials intended that you would realize that you were a subject of the Emperor who knew that “death was as lighter than a feather.” One understood what it meant to be part of this shared category by taking part in a shared activity with all of the nation’s other school children. In the proper hands (or the wrong ones), the martial arts would seem to be machines for the construction of what Benedict Anderson called “imagined communities.”

Our personal experience of the martial arts is by definition an individual matter, and one that often appears far removed from political considerations. It is widely considered to be a breach of etiquette to bring up politics in the training hall (a point that I want to explore below). Yet the martial arts cannot exist as a purely solitary activity. As everyone who has ever examined these practices has noted, they are fundamentally social in nature. They arise from, and give new life to, social communities. Politics, in turn, is the mechanism by which societies allocate resources and responsibilities to various groups. While many individuals are drawn to the martial arts because they seek a uniquely personal experience of individual empowerment, the social nature of our communities makes them vulnerable to many competing political claims.

Understanding “Normal Politics”

How one evaluates this conclusion will vary. I suspect that for many readers the discovery that the martial arts are inherently political would be something of a disappointment. Given the ever-growing levels of polarization and acrimony between the left and right in both Europe and North America, many of us are actively looking for communities that offer a reprieve from the constant state of social warfare that we find in our social media feeds or on the 24-hour news cycle. I myself am highly sympathetic to this sentiment. It is hard to escape the feeling that the very word “politics” has come to be tainted.

Still, as a political scientist by training, I tend to see everything as having a “political” aspect. One might call it an occupational hazard. Yet politics actually takes many forms, several of which are not all that closely related to polarized left-right debates of the day. As a means of resolving our differences, within a nation, a community or an organization, politics is usually a better option than conflict or violence. Indeed, the creation of the right sorts of political institutions and norms can lead to long periods of stability, growth and social harmony.

The assertion that the martial arts are, and have always been, inherently political should not be seen as a condemnation. Rather, it simply acknowledges the fact that the communities we create are socially meaningful. We do not just generate feelings of personal empowerment. Through our practice we create ideas, norms, networks, and reserves of social and human capital. We cannot really understand the roles and meanings of the martial arts in the modern world without thinking carefully about the political implications of all of this.

Recently the association between certain violent white nationalist organizations and peripheral aspects of the MMA community has been grabbing headlines. Within the martial arts community this has been debated here and here. In my own response to these stories I attempted to introduce some basic principles from institutional analysis to ask how the spread of violent ideologies within something like the martial arts community might be contained.

All of this represents a good first cut at the problem. But if we are going to have a sustained discussion on the relationship between politics and martial arts, I suspect that these sorts of extreme cases might not be where we actually want to start. Before delving into the pathologies of political conflict, it is helpful to study more typical cases of ordinary competition. Only once we have established a baseline of how the martial arts might become involved in “normal” political disputes will have an ability to understand what has gone wrong in these other cases. Better yet, as we establish a baseline it becomes clear that under a fairly wide set of conditions martial arts communities can actually play an important role in bridging conflicts, building social trust and preventing the spread of violence. Indeed, seemingly apolitical choices regarding the structure and regulation of these communities, rather than anything inherent in the embodied practice of the martial arts themselves, will have a critical impact on their ultimate social destiny.

The Way of the Lightsaber: A Star Wars Story

How might the martial art actually help to repair a fractured political discourse? Perhaps an example from my recent ethnographic research with a hyper-real martial arts community might help to illustrate this potential.

It may come as a surprise to discover that not everyone in the lightsaber combat community is a diehard Star Wars “super-fan.” In my personal experience most hardcore fans, while they might collect lightsabers, do not find the notion of daily training in their use all that interesting. Likewise, while I have never met a person in a lightsaber combat class that really disliked the the Star Wars franchise, maybe half of the people could only be classified as “causal fans.” Indeed, it seems that more people actually stay in the lightsaber classes for the martial arts training and comradery than the Star Wars per se. That probably explains why one (paradoxically) does not always hear a lot of discussion of the films or other properties before, during or after your average class.

Still, there are the occasional exceptions. In one such case, earlier this spring, an emotionally charged debate briefly erupted about the merits of Rian Johnson’s highly controversial film, “The Last Jedi” (TLJ). One student (a young working-class Caucasian male), began to hold forth as to how the film was a political insult, overtly feminist and actually part of a well planned conspiracy by the Disney corporation to drive fans like him away so that they could “steal” the franchise for themselves. Statements like this are pretty common in on-line fan discussions, but not in this particular lightsaber class. It was all the more shocking as this particular student had never really expressed any animus towards the franchise before. In fact, he had never expressed any sort of political opinions at all.

What followed was a sharp exchange with a couple of other students who objected either to his perceived attacks on specific social issues (in this case gender inequality) or his notion that Disney somehow needed to “steal” a property that they already owned simply to spite him. At this point he declared that he was done with Star Wars and would be boycotting all future films, but not, of course lightsaber practice. Everyone left unhappy. Still, the next week everyone was back as if nothing had happened.

I have no idea whether the student in question made good on this threat to boycott the upcoming film, Solo: A Star Wars Story. I should probably ask him sometime. But in a sense, it doesn’t really matter. This guy is one of the more senior students at the Central Lightsaber Academy and a real stalwart of the local community. At the time he made two things perfectly clear: his utter contempt for what he saw as a personal political attack by Rian Johnson which “ruined Star Wars” and, secondly, that no matter how angry he was about this, it wasn’t going to impact his place in the lightsaber combat community. Nor has it. I forgot that this incident had happened until a recent article in the news sent me back to review some of my fieldnotes.

As anyone who follows the Star Wars fandom can attest, arguments such as the one documented above have been very common occurrences in the wake of the TLJ. Unfortunately, they don’t all have such tidy resolutions. Like so much else in our current environment, Star Wars has become a highly politicized subject. Progressive fans and commentators have associated characters like Princess Leia, Rose Tico or Rey with not only “The Resistance” against the First Order (a fascist political movement shown in the new trilogy), but also “the resistance” against Donald Trump. In an attempt to make amends for previous charges that the series marginalized minority or female characters, Disney has actively moved these progressive discussions to the forefront of multiple Star Wars properties. And while many fans have been happy to accept some projects (Rogue One has proved to be quite popular) while rejecting other films that they found to be flawed on a technical level (often The Last Jedi), a not insignificant and vocal minority of critics have connected their dislike of the recent films to a pattern of alt-right, misogynist and racist trolling.

Yet when looking at a heated facebook thread it can often be difficult to determine the size of these groups separate from simply their volume. Cultural critics have been left to wonder how much of this debate was being driven by Rian Johnson’s questionable directorial decisions (specifically, the pacing of the Casino sub-plot, and the general irreverence with which Luke Skywalker was treated), and how much of it was overtly political. In other words, was Johnson’s movie really that divisive, or did an already polarized American public simply adopt his film as a yet another proxy battlefield in the era’s raging political debates?

Morten Bay, a newly minted UCLA PhD and current post-doc at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School, recently decided to find out. He has posted an unpublished draft of a study that began by collecting all of the tweets directed to Rian Johnson for a seven-month period following the release of TLJ. These were coded as negative, neutral or positive, and then used to construct a database describing all of the accounts that had publicly engaged Johnson in the debate. (Obviously this debate happened in many other places as well, but the author was forced to stick to a sample set of about a thousand observations by the all too familiar constraints of budget, time and computing power.)

Interested readers can review Bay’s work here. I have quite a few thoughts on this paper (and a number of criticisms) but will resist doing a full review as it would take us to far afield from the politicization of the martial arts. Still, the broad contours of his findings are interesting and most likely reliable.

While the majority of Star Wars fans actually liked The Last Jedi, there was a sizable, and very vocal, minority who did not. And while some of them were genuine Star Wars fans who simply objected to Rian Johnson’s directorial choices (and sometimes engaged in troll-like behavior), a careful analysis of all twitter accounts in the dataset suggested that others were something else entirely. Bay found evidence that a large number of accounts egging on this corner of the twitter debate were linked to individuals who showed little interest in Star Wars and instead functioned as conservative or alt-right activists. More disturbingly about 5% of these accounts closely fit the profile of the Russian troll farms that had waged a campaign to sow social chaos and disinformation during the 2016 presidential election. Bay was able to confirm his suspicions when he showed that several of the most prolific accounts targeting Rian Johnson were later closed by Twitter in its purge of accounts known to be operated by Russian troll farms.

Martial Arts and the “Social Cleavage” Problem

The good news is that if you have found yourself thinking that the recent discussion of pop culture franchises have become overly political, it is not just you. These properties have developed into sites of sustained political debates and even (at times) information warfare by those who wish to publicize claims of “social chaos” in the Western democracies. Even the entertainment franchises that used to unify society through a few hours of simple escapism are increasingly being weaponized as part of larger political conflicts.

It was Bay’s paper that inspired me to look back over my own fieldnotes for this period. I was forced to wonder at the different ways that similar debates played themselves out online versus within a lightsaber combat school. In both cases basic demographic characteristics were highly correlated with the roles that people assumed in arguing for or against TLJ.

Social scientists have known for some time that in the modern West political affiliation is just about the most fundamental type of identity that most people have. Indeed, Americans will switch religions to fit their politics long before they modify their political beliefs to satisfy the demands of religious teaching. Likewise, demographic factors (race, gender, education level, income, etc…) also tend to be highly correlated with partisan identification. It is thus not difficult to believe that the argument that erupted in the Central Lightsaber Academy that day was perhaps only peripherally about Rian Johnson. It stung the involved individuals precisely because personal frustrations and political identities lurked in the background.

This is also when a social scientist would expect to see some sort of more fundamental rupture in a community. When personal characteristics such as income, education, gender and ethnicity become politically salient they are called “social cleavages.” These divisions can structure large scale conflicts in both society and the polity (e.g., the working class vs. capitalist, urban vs. rural values, male votes vs. female votes).

Democracy tends to work the most efficiently when the various cleavages do not overlap. In that case a political party might sometimes form an alliance with urban factory workers, and in the next instance with rural agricultural interests. That sort of flexibility makes compromise easier and it tends to moderate political polarization. After all, your antagonists on one issue may be your allies tomorrow. In such a situation our cleavages are said to be “cross-cutting.” It is more complicated when our cleavages perfectly align with each other. When we can always guess someone’s party alignment based on their economic class, race and whether they live in an urban or rural mailing code, it becomes vastly more difficult for parties to make deals and reach compromises. The winning and losing coalitions are simply too stable. Neither side will have an incentive to lessen polarization, and politics rapidly becomes a zero-sum game. In this situation trust erodes, and in a few cases one side or the other will begin to look for ways to capture more of the gains of the political system by excluding the other from full participation in the decision-making process. That is the difference between vigorous debate within a democratic framework and a politically extremist attempt to unilaterally change the nature of the political community.

At least this is what we typically teach our students about social cleavages and voting in introductory classes on voting theory. And its why the debate within the Star Wars fandom is, to a political scientist like myself, so disturbing. It is yet another piece of evidence suggesting that increasingly all the most salient social cleavages in America today are overlapping, rather than cross-cutting. That portends bad things in the long run.

It is also why we should be interested in how martial arts communities function in these environments. In the case I outlined above a very vocal, surprisingly emotionally charged, outburst was quickly forgotten and put away. I suspect that if a similar conversation had erupted in an online environment the resolution would have been much different. Yet in this case the conversation happened within the walls of a martial arts school. And the martial arts have a unique ability to add yet another layer to one’s personal identity.

Of course, identity is always situational. How I define myself at any given moment depends in large part on where I am and what is socially appropriate at that time. But somewhere in the back of my head there is always that recognition that I am a “wing chun guy,” and there is always a spark of social recognition when I meet a fellow student of the Chinese martial arts. After all, there aren’t that many of us, and the one thing that each of us needs is a community.

Likewise, lightsaber combat can only be learned in a social setting. One has got to put in a lot of hours with many training partners to gain basic skills. Weapons work requires a lot of focus and trust, even when the weapons in question do not technically exist. One still has to trust that your partner will not hit you simply because they are tired and frustrated. And it is hard to deny the sort of visceral bond that is created (Victor Turner might have called it “communitas”) by simply going through this process together. While other markers of social status will always exist outside the school, martial arts instruction has a remarkable ability to take a diverse group of people, strip them of many individual aspects of identity, and then allow them to grow into a new sort of community together. We should not underestimate how powerful and rare that experience can be in the modern world.

When that happens there is the possibility that one will create a new identity which cross-cuts the existing social cleavage. As we saw in the case illustrated above, this can help to ameliorate other sorts of political debates. Indeed, our trust in, and dependence on, individuals who are very different from us within our martial arts communities may help to insulate us against more radical discourses that would seek to target them. Students of social capital would even suggest that trust is basically a learned skilled, and the lessons that acquire within a martial arts community can eventually be applied to other areas of the civil sphere. This in turn is critical to ensuring the proper function of modern democratic institutions.

Conclusion

It is not difficult to look at practically any important problem in the world today (whether its economic, environmental, social or cultural) and to discern political forces lurking in the background. What is sometimes harder to remember is that most positive developments are also the result of careful institutional design and a different sort of political calculus. If we focus only on cases where extremist groups have sought to co-opt martial arts practices, it may be all too easy to conclude that there is something dangerous about the martial arts themselves. Lacking a complete view of the wider social context, researchers might conclude that these practices are inherently violent, in either a physical or a social sense. Social elites in late 19thcentury China certainly came to that conclusion, and the end result was a lot of legislation that further marginalized the martial arts community without addressing any of the more fundamental causes of social violence that it increasingly drove the logic of Chinese decline.

The foregoing essay has argued that the martial arts are interesting (and in some senses inherently political) because they are social practices that generate new types of community identification. This is precisely why Asian nationalists and reformers promoted them throughout the region’s turbulent 20thcentury. It is also why individuals who care about the quality of civic life in our ever more polarized world should also take these practices seriously. The embodied nature of martial arts practices has the potential to build community bonds that can cross cut other, highly politicized, social cleavages. Both on-line Star Wars conversations and embodied lightsaber practice generate communities. Yet one seems much more likely to resist politically induced conflict than the other. The promotion of these practices, when properly understood and carried out, could literally help to heal our civic institutions.

This is not to say that the creation of martial arts schools should be seen as a panacea. Given the realities of geography and economic inequality, it is unlikely that all martial arts schools will be equally diverse. Because these sorts of institutions are essentially voluntary organizations the danger is that we will choose to associate only with individuals who resemble ourselves. That outcome would be counterproductive as it might actually reinforce, rather than offset, the problem of overlapping social cleavages.

Yet in practice that does not seem to be an insurmountable problem, at least not in my area of country. Fellow kung fu students are rare, and lightsaber combat enthusiasts even more so. Economic necessity dictates that most schools are at least somewhat diverse as they are forced to recruit many types of students from a large geographic area just to make ends meet. And this is precisely why so many of us are willing to set aside random political discussions when we enter our training spaces. Good training partners (or instructors) are hard to find, and we all have a sense that in an increasingly polarized world there is something “more important” than the latest controversy to consume the 24-hour news cycle. Ironically, it is that seemingly agnostic impulse that suggest the real political value of the martial arts today.

oOo

If you enjoyed this discussion you might also want to read: Theory and the Growth of Knowledge – Or Why You Probably Can’t Learn Kung Fu From Youtube

oOo