The Problem with Play

I have always found TED talks to be a mixed bag. Some are wonderful. Others I find vaguely irritating. But the project itself, which seeks to popularize some of the most important “big ideas,” is deeply interesting. If nothing else, scrolling through a list of titles on the video platform of your choice is a good way to see which concepts are currently making their way into popular consciousness. That is important as scholars are increasingly being judged by the sorts of “real world” effects that their research generates.

If the “TED Index” has any validity, there is one idea whose time has truly come. “Play” is back. After decades of being little more than a term of abuse, a purposeless activity relegated to the realm of childhood, play has recently become an important concept. While few individuals, other than a handful of psychologists and evolutionary biologists, thought about play a decade ago, today studies are being conducted, grants are being written and (many) books published.

This material seems to have come to a general agreement on a few key facts. Play is a very important aspect of human (indeed, all mammal) learning and development. Individuals who are artificially deprived of play tend to be less creative, flexible, resilient and have an increased likelihood of psychological disorders. The rise of anxiety, depression and suicide in the Western world, while typically blamed on cell phones and Facebook, also corresponds with the increasing displacement of all forms of play from the lives of tightly scheduled children and young adults. It seems that the entire TED circuit speaks with a single voice when they tell us that we are facing a crisis. As Weber’s iron cage of modern rationality grinds on, play has become an endangered species. The result is a society filled with less creative, less sociable, and less psychologically resilient individuals, precisely at the moment when we need those sorts of attributes the most.

Nor is this simply a matter of concern for parents and school administrators. While most mammals retain some interest in play, humans are practically unique (or at least right up there with dolphins and sea otters) in that extended periods of play remain necessary for adults as well. As one of the afore mentioned TED talks noted, the opposite of play isn’t “work.” Its depression. And that quip brings us to the heart of our problem. Play has a branding problem. Can the martial arts help?

As with so much else, I blame the Puritans for all of this. The advent of the protestant work ethic represented a fundamental break with traditional modes of social organization across large portions of the West. While there is much that we could say on the topic (indeed, entire books and articles have been written on the subject), for the purposes of the current post it is enough to note that frivolous activities came under severe scrutiny in a society where an individual’s personal value became increasingly conflated with their net worth. After all, the one thing that no society can abide is an individual who fails to take its values seriously. In short order “play” came to be regarded with suspicion.

Nor has the increasing secularization of society done anything to alleviate this problem. If anything, it has gotten far worse in recent decades. School years are longer now than they were two generations ago, and seemingly secondary subjects like music, art and recess have all found themselves on the chopping block. The sorts of athletic leagues that most children find themselves in today are so tightly supervised and disciplined that they no longer meet even the most basic definitions of play. Indeed, the need for constant resume building has eliminated much of the unsupervised “downtime” in which childhood used to occur in.

Martial Arts Practice as Play

This is the section of the essay where I typically introduce martial arts practice as the unexpected solution to what ever issue kicked off our discussion. Unfortunately, the relationship between the martial art and play is complex and multilayered. On the one hand, these practices have been haunted by the widely held perception that they are not something that “serious” people do. Spending an hour a day training for your half marathon is fine, even admirable. But spending that same hour in a kung fu or kickboxing class can elicit sideways glances and nervous laughter. Paul Bowman tries to unwrap what is going on here in the opening chapters of his volume Mythologies of Martial Arts(2016). His arguments are well worth reviewing. But in brief, the alien and seemingly pre-modern nature of the Asian martial arts makes it difficult to incorporate them into Western society’s dominant discourses.

The health benefits of jogging are obvious, as are the competitive virtues of winning a 10K race. They require no explanation. Yet one must always explain that kickboxing is a great workout, or that BJJ “burns a lot of calories.” Martial artists are constantly, and with only partial success, justifying the resources that they spend on their training. Yet at the end of the day, for most members of society, this will always be “just playing around.” Children may get some benefits from martial arts training. But Master Ken remains a telling image of the overly serious adult student who never managed to grow up. Serious martial arts training remains unavailable to many adults precisely because it is perceived as a type of (delusional) “play.”

The irony is that many, maybe even most, martial arts class rooms are devoid of actual play. Real play, true play, can be antithetical to the goals of many martial arts schools. To understand why this is we need to think a little more carefully about play itself. Unfortunately there are lots of definitions floating around and they don’t all agree. Still, I know play when I see it. For a short essay like this a compete clinical definition probably isn’t necessary. Luckily there are a few broadly held points of agreement that can guide our thinking.

To begin with, play is not the same thing as inaction or simply a lack of seriousness. It is an independent process in its own right, with both psychological and social aspects. There are many types of play. Some are deeply imaginative and others are not, being primarily observational or embodied. True play is an independently chosen activity that happens in the absence of a directing authority. It is basically a truism to say that no one can force you to play. Play is generally seen as being purposeless. This does not mean that it has no impact on an individual’s life. Rather, it happens for its own sake. To summarize, fun activities are “play” only if they are self-controlled and self-directed.

A psychologist or social scientist may look at what happens in the average Taekwondo class and see a highly creative modern ritual. Individuals dress in symbolic clothing and engage in rites of reversal that upend mundane social values (such as don’t hit your friends or choke your siblings). And yet many training environments go out of their way to avoid an air of playfulness. In its place we find the formality of ritual and the constant supervision (and correction) of concerned teachers. Indeed, the parents of the children in the class are likely to be found on folding chairs in the school’s lobby, closely monitoring everyone’s progress. This is a type of performance staged for social purposes rather than individual play. Much the same could be said for most school sports.

One may have quite a bit of fun in such a structured martial arts class (I know I always do). And there is no doubt that students learn and derive all sorts of physical and social benefits from participating in such classes. And yet all of this is basically the antithesis of play. The general feeling seems to be that not only would play in a martial environment be unproductive (how can one learn “good habits” without constant correction and oversight?), but that it might also be dangerous. Just stop to think about the arsenal of weapons that line the walls of the average kung fu school? Do you really want to turn the students loose for long periods of unstructured play? Perhaps the opposite of play is actually “liability insurance.”

Luckily my own Sifu didn’t seem to believe that last point. I can confidentially say that unstructured play was critical to my development as a Wing Chun student. Indeed, it was an important part of the curriculum.

Standard classes, graded by level and each having a well-developed curriculum, were held four nights a week at Wing Chun Hall in Salt Lake City. Yet Jon Nielson, my Sifu, was aware that more was needed when attempting to find your own place in the martial arts community. So every Friday evening and Saturday morning his school would open for three hours of unsupervised “practice time” for anyone who wanted to come. Students of the Wing Chun Hall were expected to attend these “open sessions” on a semi-regular basis (and there was never any cost for doing so). Even individuals from other schools were welcome to come by and train with the Wing Chun people if they so desired. The critical thing, however, was that the one person who was rarely ever there was Sifu. The sessions were instead monitored (but not run) by his junior instructors who were under strict orders to help if asked. Otherwise students were left to train how they saw fit. If someone wanted to learn some basic dummy exercises, even though they were years away from starting the dummy form, this was their time to do it.

Most people would come to an open session with some sort of goal in mind. Maybe they wanted to work on a specific form. Perhaps they were having trouble with ground-work, or one of the paired exercises that had been introduced during the week. And it goes without saying that everyone wanted to practice Chi Sao with the more senior students (or to touch hands with visitors from different styles).

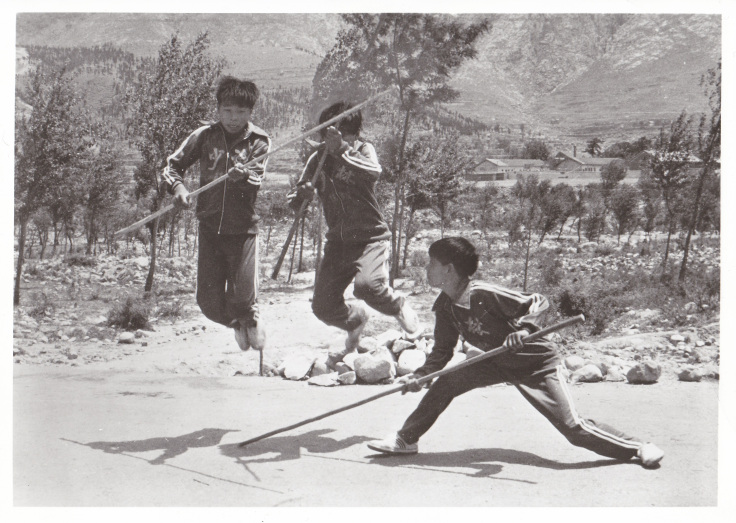

Yet three hours is a long time. One would inevitably be drawn into all sorts of other drills, exercises and discussions that you had never envisioned. The second and third hour of any sessions always seemed to evolve organically. One might well come in to work on the dummy and end up with a pole in your hands. I still have fond memories of one Saturday spent making up a game so that new Siu Lim Tao students could practice their footwork. While these open sessions tended to start out as directed and focused, by about hour two things had become much more fluid.

My sifu instituted these open sessions for a couple of reasons. To begin with, everyone needs a night off. And we can all use more hours of practice when it comes to the sorts of sensitivity drills that Wing Chun so loves. These things are not like riding bike. Once certainly will forget them, and you are never any better than however many hours of practice you put in the month before.

Beyond that, my Sifu was also a keen student of pedagogy. He carefully explained to me the importance of unstructured play, free of judgement or overbearing correction, in learning any physical skill. More specifically, he noted that this was where students would learn to trust their bodies, bodies that were now defined through a new set of skills. And it was those martially educated bodies that would make judgements about the world. Understanding whether someone was a threat, or whether a technique was working, was an embodied process. Teaching and drilling this material during the more structured nightly classes was not enough. It was also a matter of how that knowledge was internalized, localized, modified and rearranged. Drawing on his background in linguistics he noted that kung fu meant “hard/skillful work” (and it certainly is), but in China the martial arts are often associated with the verb “to play.” One “plays wushu,” or goes to “play sticky hands.” Both modes of action, he suggested, exist in a reciprocal relationship. Self-controlled and self-directed play is not disposable or supplemental. Properly understood, it is a critical aspect of the learning process.

A Common Sentiment

I had not thought about my teacher’s open sessions (and how much fun they were) in a while. But earlier this week I bumped into an old friend at the grocery store who had recently returned to the US after living abroad. She asked how my martial arts training was going and, while mentioning my various projects, I noted an upcoming workshop with a guest instructor that I would be hosting for the lightsaber combat group here in Ithaca.

My friend already considers my Chinese martial arts practice to be strange enough. But apparently she had been gone long enough that she didn’t know about the lightsaber project. It elicited a laugh hinting at something other than delight. Still, laughter from the uninitiated comes with the territory when one is holding a lightsaber (or, if we are being totally honest, any other type of sword). I noted that, if nothing else, it is easier to fill a class with lightsaber students than, say, the traditional Wing Chun swords. She immediately noted that she would be much more likely to come to the later, “but to each their own.”

This was not the first time I have heard something like this. When explaining to curious passersby that our lightsaber system is based, in large part, on traditional Chinese swordsmanship, this is actually a pretty common response. Everyone it seems, is more interested in “serious” fencing or maybe Wudang sword practice. And yet we all know that the vast majority of these individuals would never actually show up for that class. Ithaca is full of highly skilled traditional martial arts teachers that struggle to find more than a handful of students. The sad truth is, to an outside observer, anyone who voluntarily spends that much time with a sword isn’t being “serious.” How could they be? Isn’t it all just for fun? You might call it training, but for most people it will always be “just playing around.”

One of the challenges facing the modern martial arts is not to internalize this common critique. It is all too easy to respond to these questions by reframing all of our activities as investments and “hard work.” Indeed, the nationalist turn taken by the Japanese and Chinese arts in the 1930s explicitly argued that the goals of hand combat practice were fundamentally a continuation of modernist project. The martial arts of the era demanded (and received) state support precisely because they argued that they had moved beyond childish things and become a means of “strengthening the nation.”

Such rhetoric was intoxicatingly effective in the 1930s and 1940s. Yet these arguments work less well in the consumer driven spaces that define the modern West. Few people want to pay $100 a month to be part of a nationalist indoctrination program.

Nor, given our increased understanding of the importance of play as an aspect of mental health, as well as its critical importance to the learning process, a move back to the “seriousness” of the 1930s would not be wise. Sadly the martial arts sector lacks the visibility to create a widespread desire for play in the West. I suppose that is the job of public intellectuals, morning talk show appearances, NY Times best sellers and (if all else fails) TED talks. Yet what we can do is to provide spaces for less-structured play in our classes, organizations and training structures. My Sifu did that for me, and it was immensely valuable. After speaking with my friend I realized that my lightsaber classes might need something similar. It is not enough that an activity is imaginative or fun. We all learn fastest when given opportunities for truly independent play.

oOo

If you enjoyed this essay you might also want to read: Red Boats and the Nautical Origins of the Wooden Dummy

oOo