–

武當劍法筆記

NOTES ON THE WUDANG SWORD ART

(浙江温嶺胡子謨記)

(Recorded by “The Beard” of Wenling, Zhejiang [Yi Fanzhai])

[1939]

[translation by Paul Brennan, May, 2018]

–

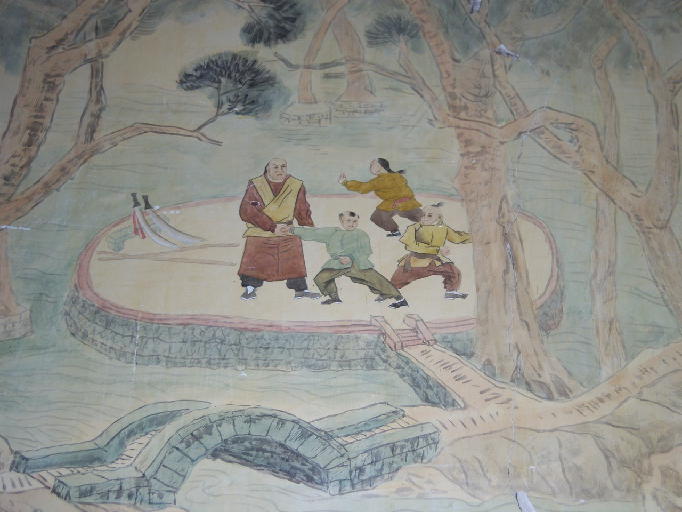

[This text which began simply as a document for personal reference survives as an invaluable record of the sword art that had been handed down from Li Jinglin, presenting the five-section two-person sword set in much greater detail than the meager outline in Huang Yuanxiu’s 1931 manual, and Huang quite rightly decided to include it in the expanded version of his Martial Arts Discussions, which was later published in 1944. It is not clear whether Huang made any adjustment to Yi’s text, with only the parenthetical comment at the end of movement 2.4 seeming a likely addition on his part.

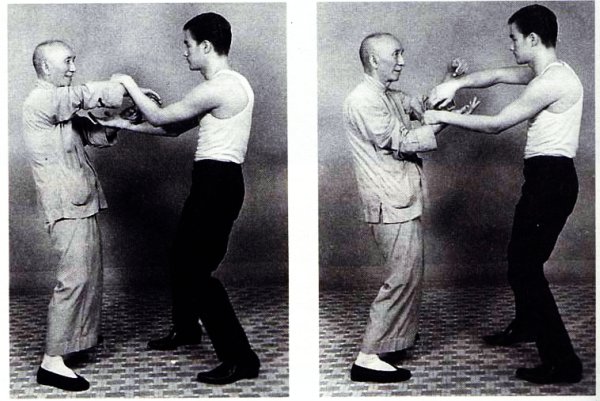

To make this text more functional, I have also plugged in all forty-one photos from Chapter Four of the 1931 book, showing Huang Yuanxiu (in the lighter outfit) and Chu Guiting (in the darker outfit) demonstrating the core techniques. These photos can be slightly confusing because Huang and Chu do not stay consistent in their roles as Person A and Person B, and the view is often shown from the reverse profile (Section Four being the only section where the roles and the view in the photos remain consistent). It is best to ignore their identities as Huang and Chu in each photo, and to pay attention only to who is portraying A and B based on their actions within any given photo. There is unfortunately not a photo for each movement, but there are enough of them to be very helpful for adding clarity to many of these movement descriptions.]

–

第一路

SECTION ONE

預備式(上手稱甲下手稱乙)

PREPARATION POSTURE (The person who makes the first move is called A, and the person who responds to it is called B.)

甲乙各執劍就位――

[1.1] A and B, each of you stand holding your sword.

左手執劍反貼左臂外方,右手垂直貼右胯傍,兩足平立,離開之距約與肩等,身體正直,目平視前方。

Your left hand is holding your sword backwards, touching the outside of your left forearm. Your right hand hangs down close beside your right hip. Your feet are standing parallel about shoulder width apart. Your body is upright and your gaze is forward.

出劍式

SENDING OUT THE SWORD [This posture is comprised of movements 1.2 and 1.3. (After PREPARATION POSTURE and SENDING OUT THE SWORD, none of the subsequent movements are grouped under specific names.)]

甲乙各交劍與右手――

[1.2] Both of you, switch your sword to your right hand.

右手戟指掌心向上,屈右腕與腰平,伸右臂向右與肩水平,頭向右轉目視右手,轉左足向左方,轉身上右足,左足微屈,右足着地,同時右手戟指向前一指,目視敵方。退右足同時轉身,兩手自左上向右後方畫一大圈,左右各收至胸前,右掌向上,左掌向下,將劍交與右手,斯時身體作勢下挫,重心寄於右足,目仍視敵方。

Your right hand forms a “spearing finger”, the center of the hand facing upward, your right wrist bent and level with your waist. Extend your right arm to the right to be at shoulder height, your head turning to the right, your gaze toward your right hand. Then your left foot turns to the left, your body turning, and your right foot steps forward, your left leg slightly bending, your right foot [toes] touching down, as your right hand’s spearing finger points forward and your gaze goes toward the opponent. Then your right foot retreats, your body turning [to the right], and both hands make a large circle from the upper left to the right rear until in front of your chest, your right palm facing upward, left palm facing downward, and you send the sword into your right hand. Your body is now squatting, the weight on your right leg, your gaze still toward the opponent.

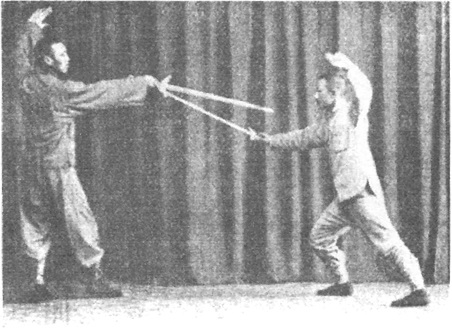

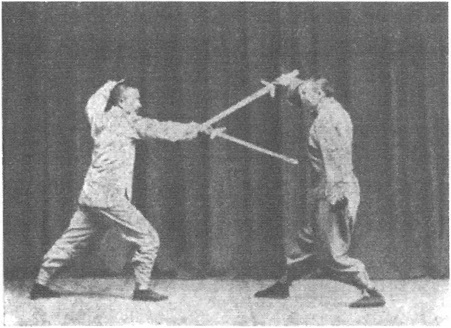

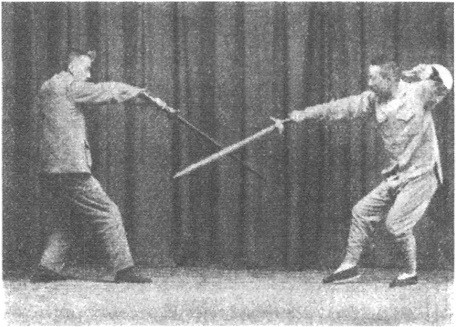

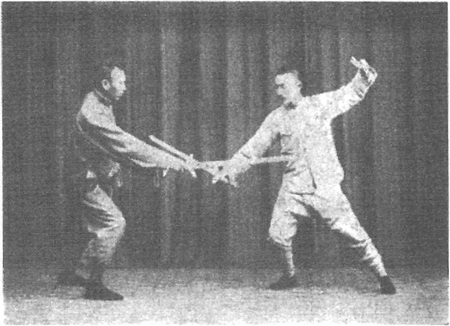

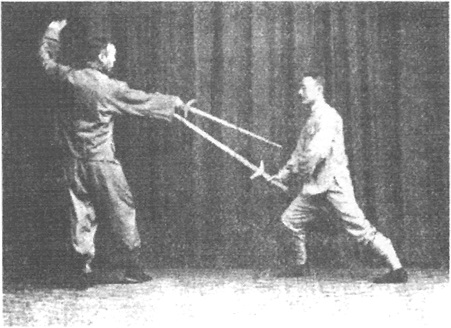

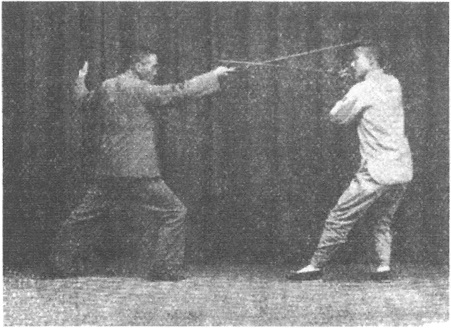

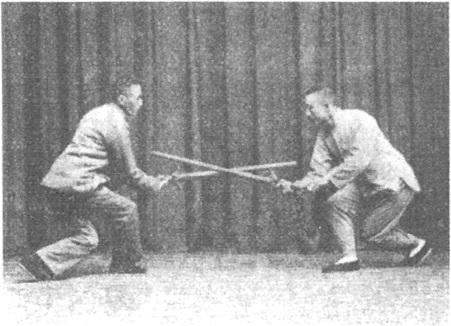

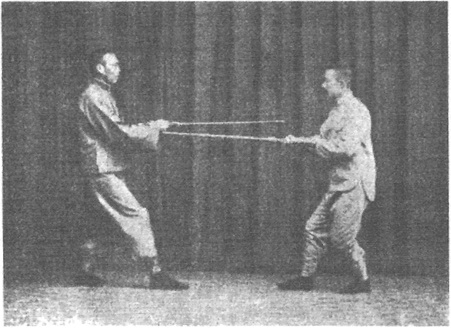

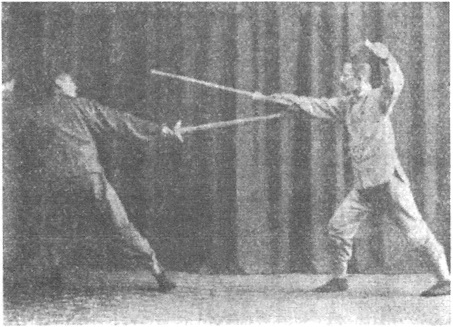

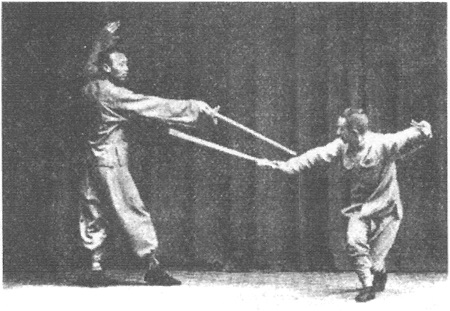

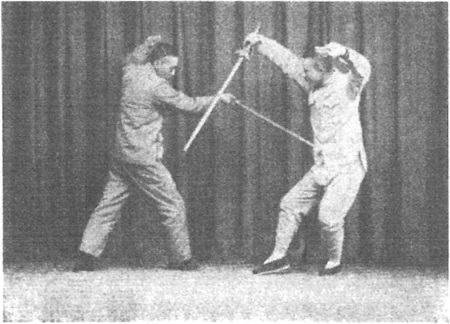

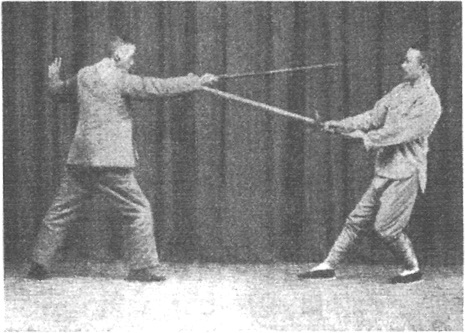

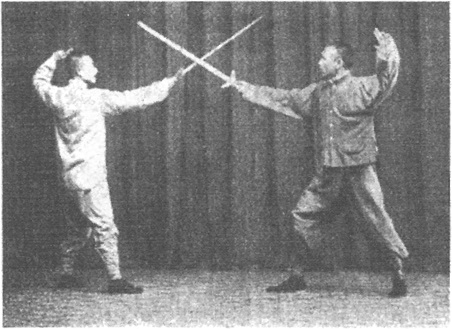

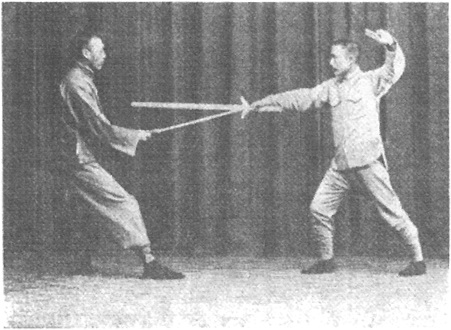

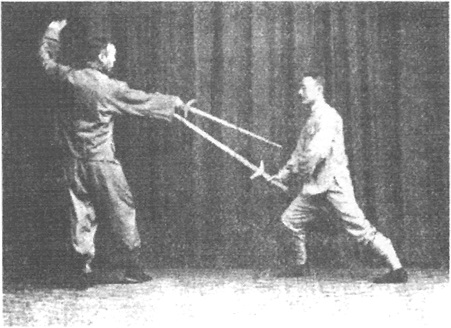

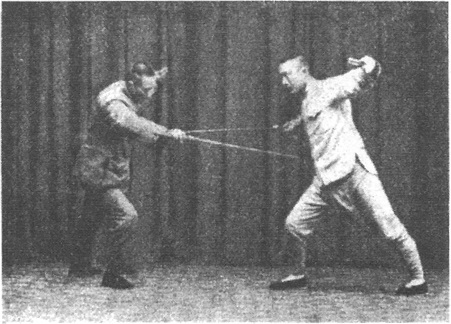

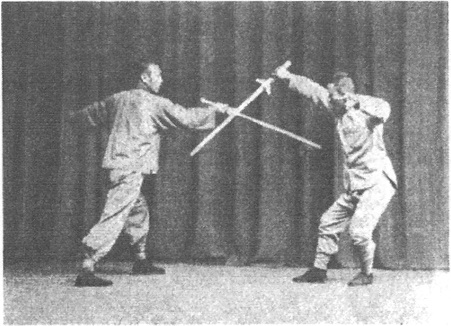

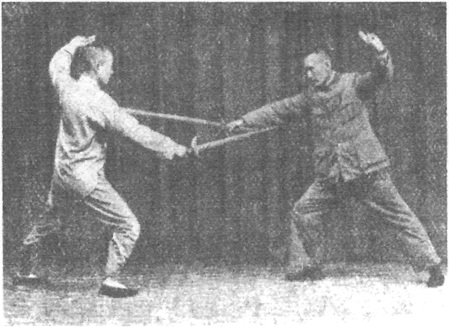

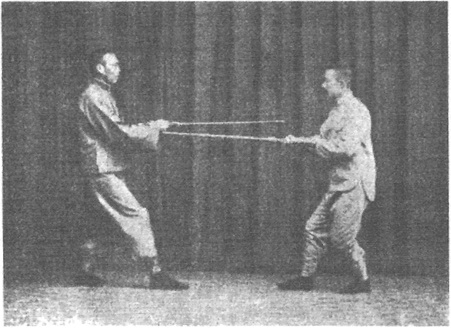

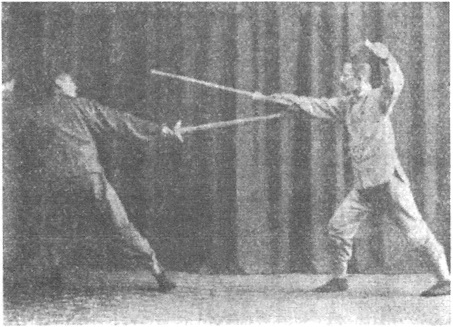

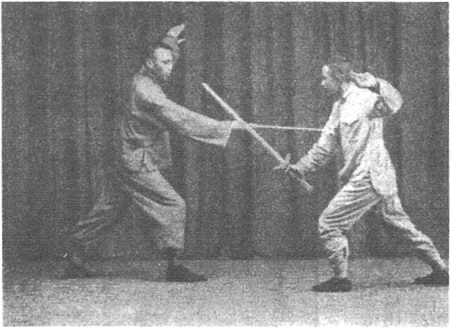

甲乙各伸劍平刺――

[1.3] Both of you, extend your swords at each other with horizontal-blade stabs.

斯時左足在前,右足在後,成弓箭步,左手戟指在左額前方,右手極力伸劍平刺,太陽劍。

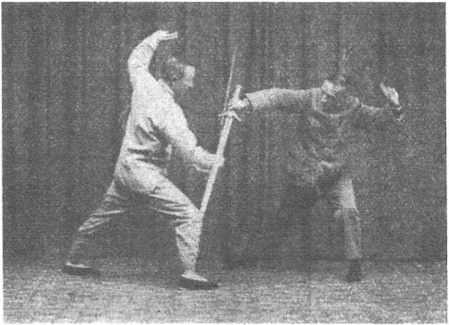

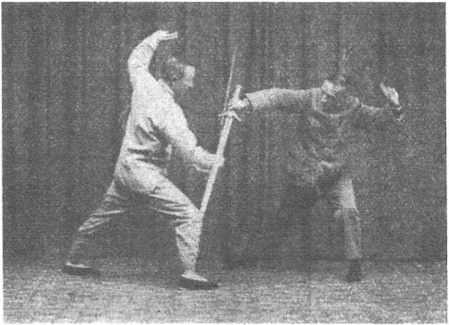

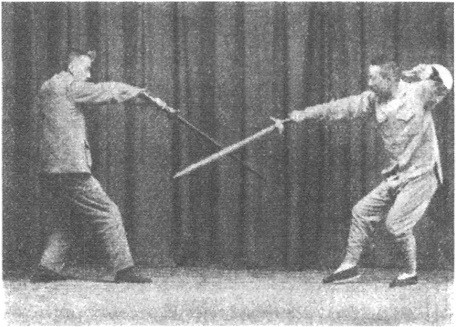

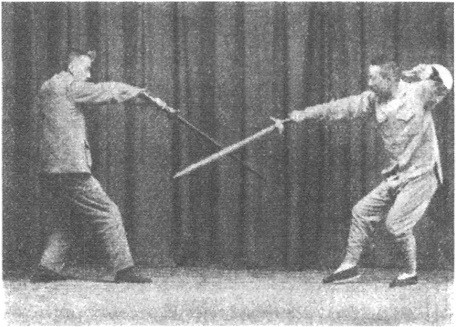

With your left foot forward, right foot behind, make a bow and arrow stance, your left hand’s spearing finger going in front of the left side of your forehead, your right hand putting all its energy into extending with a horizontal-blade stab, using a “full active grip” [i.e. tiger’s mouth facing to the right]. [The photo for this moment shows A and B closer to each other than they would be yet, with B already stepping his right forward to begin the next movement.]

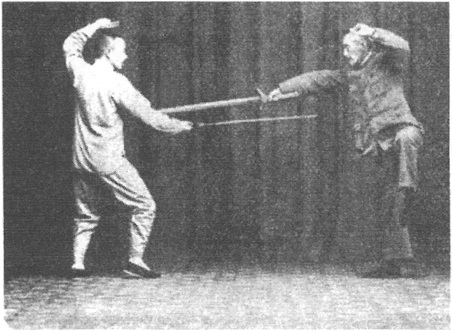

[photo for movement 1.3, showing A on the left, B on the right]

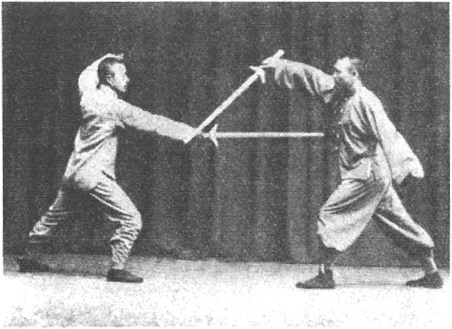

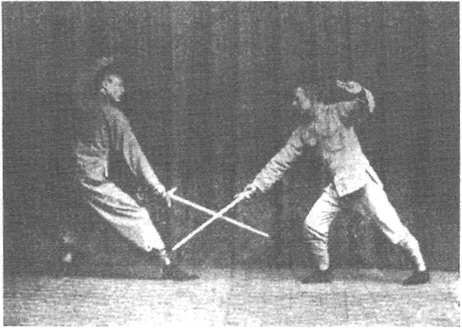

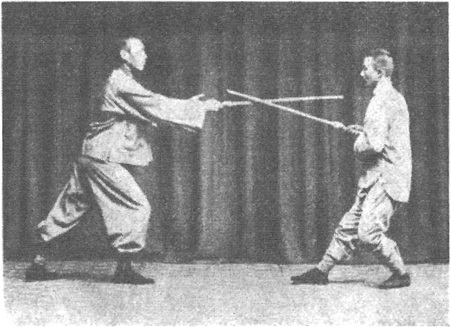

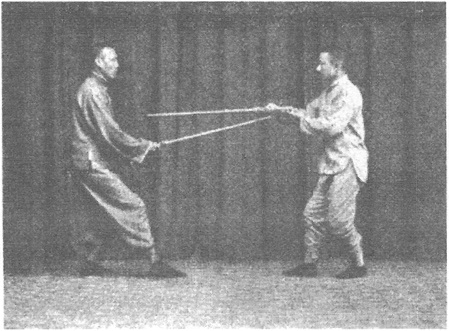

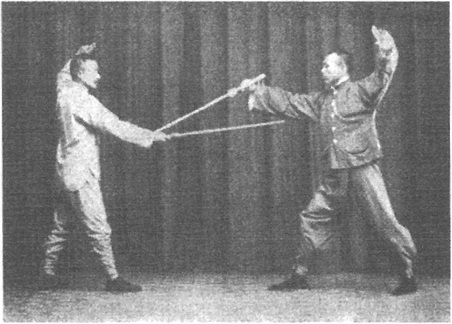

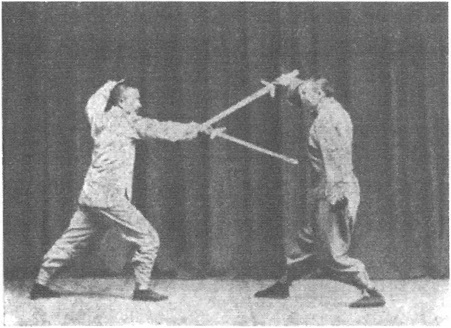

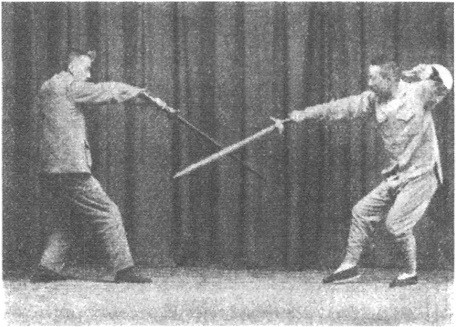

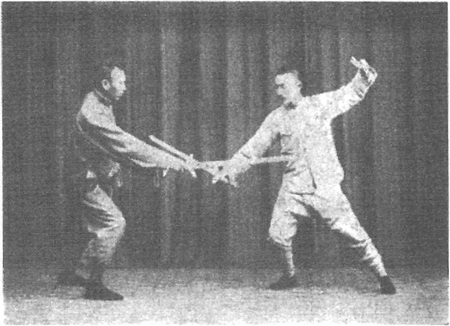

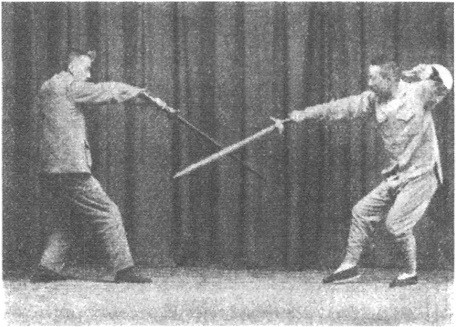

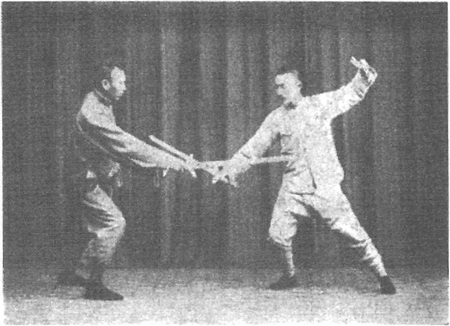

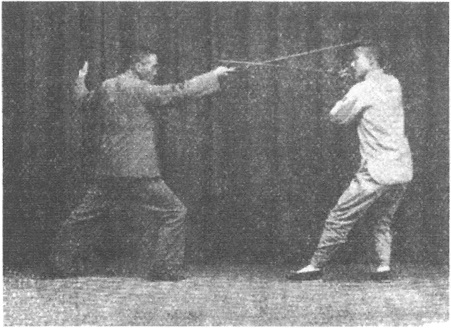

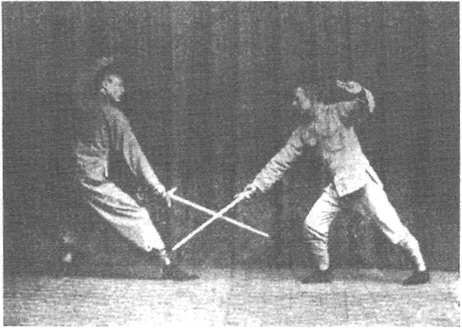

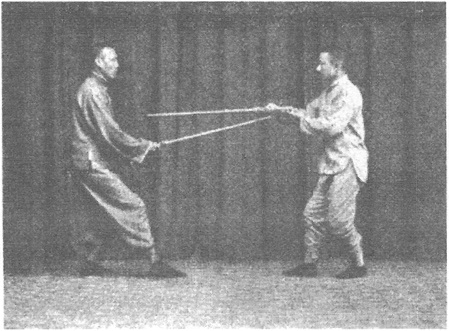

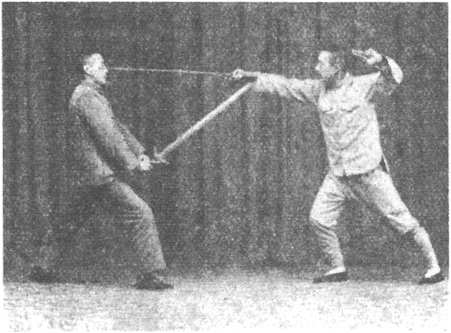

甲乙對反繃――

[1.4] Both of you, do an overturned flick to each other.

右足進一步立定左足作探步,蹲身向下,左手戟指微屈臂向左,右手以中陽劍反繃,頭向右,轉目注對方之腕。

Advance your right foot a step, stand firmly on it, and make a reaching step with your left foot, squatting your body down, as your left hand’s spearing finger goes to the left, the arm slightly bent, and your right hand uses a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward] to do an overturned flick. Your head is turned to the right, your gaze turned to your opponent’s wrist.

[photo for movement 1.4, showing A on the left, B on the right]

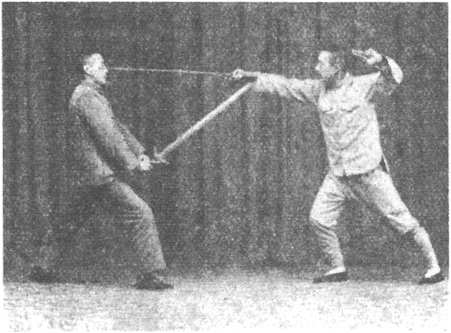

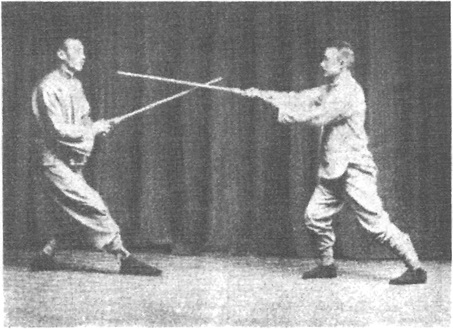

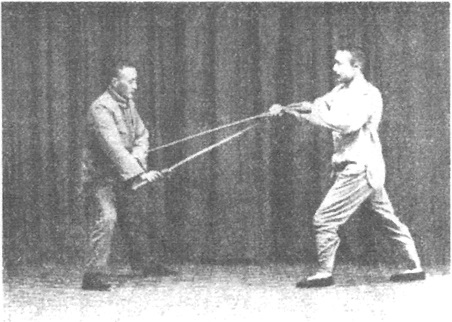

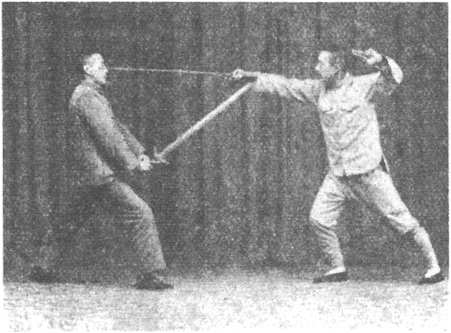

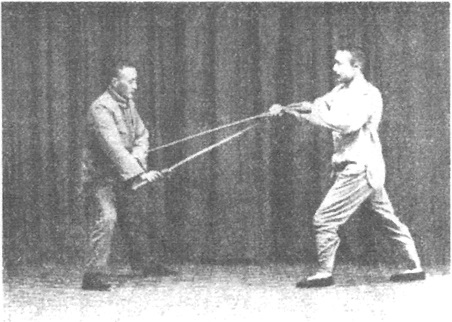

甲點腕――

[1.5] A, tap to B’s wrist.

突然起立轉身收左足,向左斜後方,半步着地,卽出右足,作預備姿勢,足尖點地,右手以中陰劍尖點敵腕,左手戟指微扶劍柄,目注敵腕。

Suddenly rise up, turning your body, withdrawing your left foot a half step diagonally to the left rear and then putting out your right foot the same as in the preparation posture, toes touching down, as your right hand uses a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to tap your sword tip toward B’s wrist, your left hand’s spearing finger slightly assisting at your sword handle [raised to the left in the photo]. Your gaze is toward B’s wrist.

[photo for movement 1.5, showing A on the left, B on the right]

[Huang later had another photo made of this situation, which appeared in his 1936 publication of Martial Arts Discussions, again showing Chu Guiting on the left in the role of A and Huang Yuanxiu on the right in the role of B.]

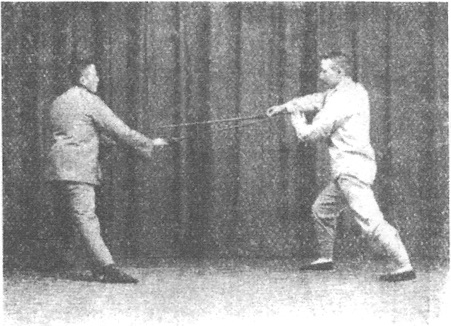

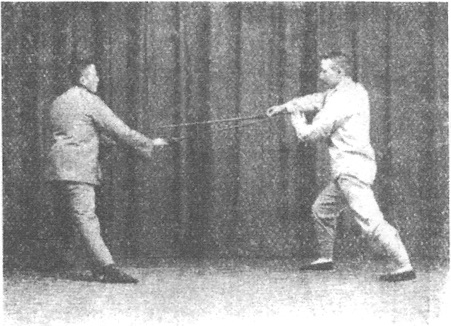

乙抽腕――

[1.6] B, do a drawing cut to A’s wrist.

乙亦突然起立,轉身立定左足,換出右足,向右後方退一步,右手以老陰劍從下方抽甲之腕,同時體重移於左足,成弓步,目視敵腕。

B, also suddenly stand up, turning your body, and stand firmly on your left foot, switching feet and sending your right foot back a step to the right rear [forward right], as your right hand makes a three-quarter passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the lower left] and does a drawing cut under A’s wrist, the weight at the same time shifting to your left [right] foot to make a bow stance. Your gaze is toward A’s wrist.

[photo for movement 1.6, showing A on the left, B on the right]

[According to the 1931 book, B follows his drawing cut by stabbing forward (with a vertical-blade stab), resulting in the extra image below (showing B on the left, A on the right, in a reversed view), meaning that A must have raised his wrist to evade the drawing cut, pulling his sword away enough to create a target for B to stab. Apparently A then responds to this by beginning the following movement slightly ahead of B.]

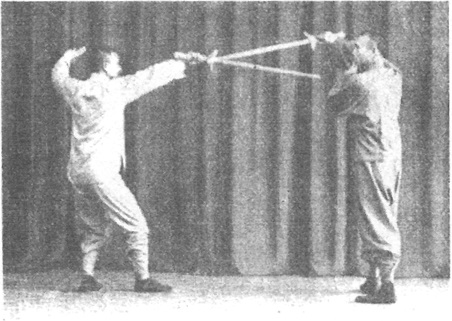

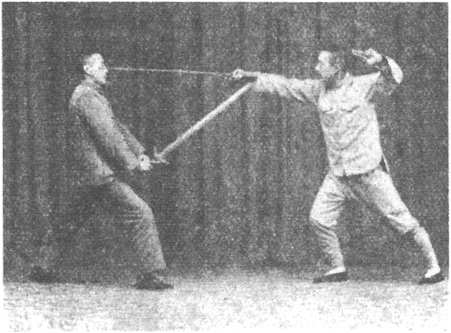

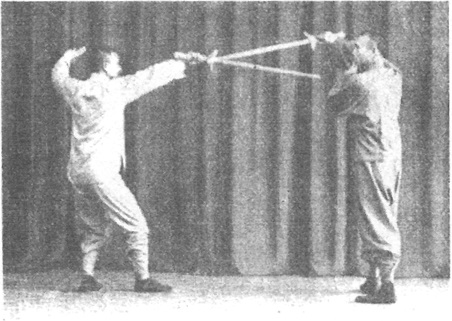

對刺――

[1.7] Both of you, stab toward each other.

甲乙各將右足後退,右手提劍前刺,(老陰劍)同時上體竭力向前探,左手戟指,置左額前方,手掌向外,目注敵方。

Both of you retreat your right foot as your right hand stabs your sword forward [and downward] into a lifting posture (using a three-quarter passive grip) [tiger’s mouth facing to the lower left], your upper body at the same time striving to reach forward, and your left hand’s spearing finger is placed in front of the left side of your forehead, the center of the hand facing outward. Your gaze is toward the opponent.

[photo for movement 1.7, showing A on the left, B on the right]

對繞走(換位)――

[1.8] Both of you, perform circle walking (switching places).

兩劍仍相交,甲乙各起右足,進步向左方繞走,對換位置,仍取前勢停止。

With your swords still touching, both of you lift your right foot and advance to the left into a [counterclockwise] circle walk, walking until you have switched places, stopping in the spots occupied in the previous movement.

乙反格――

[1.9] B, do an overturned block.

乙以中陽劍反格甲腕。

B, use a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward] to do an overturned block to A’s wrist.

甲帶――

[1.10] A, do a dragging cut.

甲將劍轉為太陽劍,同時將肘往下一沈,劍往左帶,身半向左轉,兩足在原位置,左實右虛,目注敵人劍尖。

[At the same time,] turn your sword to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right], sinking your elbow down, and do a dragging cut to the left, your body turning halfway to the left. Your feet will stay where they are, left [right] foot full, right [left] foot empty. Your gaze is toward B’s sword tip. [Following the pattern of the next movement, 1.9 and 1.10 should probably have been written in reverse order.]

[photo for movements 1.9 & 1.10, showing A on the left, B on the right (reverse view)]

[Huang had another photo made of this situation, appearing in his 1936 book. In this photo, the partner on the left is Ye Jingcheng in the role of A, with Huang Yuanxiu again on the right in the role of B.]

乙帶腰甲反格乙腕――

[1.11] B, do a dragging cut to A’s waist. A, do an overturned block to B’s wrist.

甲見乙腕避去,已為我劍所不及,趁勢轉為太陽劍,帶乙之腰,乙卽含胸轉腰,避過甲劍,同時將劍變為中陽劍,反格甲腕,如是往復三遍。

A, when you see B’s wrist evade and that your sword will miss, take advantage of the situation by switching to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] and doing a dragging cut to B’s waist. B, hollow your chest and turn your waist to evade A’s sword, at the same time switching to a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward] and doing an overturned block to A’s wrist. Go back and forth in this way for a total of three times.

[photo for movement 1.11, showing B on the left, A on the right]

乙壓劍貫耳――

[1.12] B, press down A’s sword and perform a “filling the ear” technique.

俟甲劍反格,正轉變帶腰時,突然將劍變為中陰劍,往下橫壓甲劍,

Wait until A’s sword switches from doing the overturned block to do another dragging cut to your waist, then suddenly switch to a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] and press down across his sword [the grip in the photo being aligned somewhat differently].

[photo for the first part of movement 1.12, showing A on the left, B on the right (reverse view)]

隨卽起身以太陽劍貫甲右耳,左手扶住劍柄。

Then raise your body and strike [rightward] to his right ear using a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right], your left hand assisting at your sword handle [although it is raised to the left in the photo].

甲直帶腕兼繃――

[1.13] A, do a vertical-blade dragging cut to B’s wrist with a flicking energy.

右手用中陰劍左手扶住劍柄。往後直帶復往下一沈,劍尖正對敵腕繃刺。

With your right hand using a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] and your left hand assisting at your sword handle, go to the rear with vertical-blade dragging, then sink your hand down so that your sword tip heads toward B’s wrist as a flicking stab.

[photo for the second part of movement 1.12 and movement 1.13, showing A on the left, B on the right (reverse view)]

[The photo above is used in the 1931 book to specifically demonstrate striking, even though it already shows the other person flicking in response, but then the book uses the variant photo below to highlight the vertical-blade dragging, even though it depicts the same striking situation. In the variant photo, Huang and Chu’s roles are reversed, as is the view.]

[Huang had yet another photo made of this situation, based on the variant photo, which appeared in his 1936 book, showing Ye Jingcheng on the left in the role of B, with Huang Yuanxiu again on the right in the role of A.]

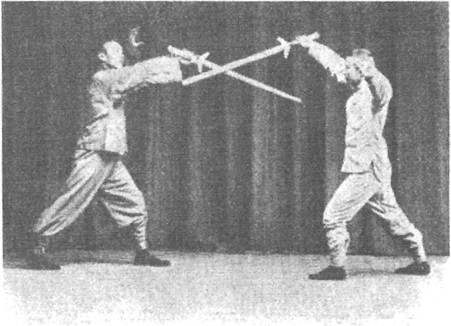

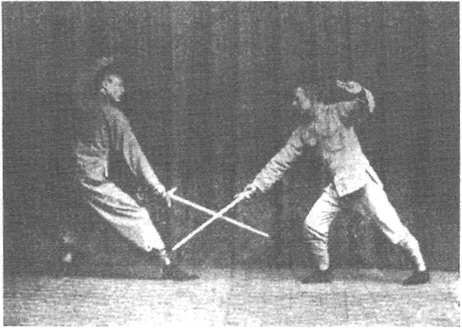

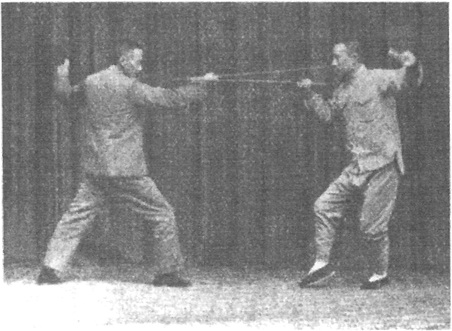

對提――

[1.14] Both of you, make a lifting posture.

乙避甲之劍尖,提腕變為老陰劍,刺甲之腕,甲亦提腕,變為老陰劍以防之。

B, evade A’s sword tip by lifting your wrist, switching to a three-quarter passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the lower left], and stab toward A’s wrist. A will also lift his wrist and switch to a three-quarter passive grip to defend against it.

[photo for movement 1.14, showing A on the left, B on the right]

對劈――

[1.15] Both of you, chop at each other.

甲乙各將劍尖自左下方向上繞一小圓圈,變為中陰劍,直往下劈攻敵之右腕。

Send your sword tip upward in a small circle from the lower left, switching you to a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward], and chop downward toward your opponent’s right wrist.

乙刺喉甲粘帶――

[1.16] B, stab to A’s throat. A, stick to B’s sword with a dragging action.

乙右手變太陽劍左手扶住劍柄,由下往上正刺敵喉,斯時劍尖向敵喉,劍柄約當自己胸下,甲亦變為太陽劍,左手扶住劍柄,劍身粘住乙劍,同時身體微向右轉,帶去乙劍。

B, your right hand switches to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right], your left hand assisting at your sword handle, and goes upward from below to stab straight toward A’s throat. When your sword tip is pointing toward A’s throat, your sword handle is just below your own chest. A, also switch to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right], your left hand assisting at your sword handle, and with your sword body sticking to B’s sword, turn your body slightly to the right and drag aside B’s sword.

[photo for movement 1.16, showing B on the left, A on the right]

甲刺喉乙粘帶――

[1.17] A, stab to B’s throat. B, stick and drag.

甲旣帶去乙劍,趁勢伸劍刺乙之喉,乙亦轉身粘帶,復反刺甲,如是三遍(太陽劍圈)。

A, once you have dragged B’s sword aside, take advantage of the opportunity to extend your sword with a stab toward B’s throat. B, now you also turn your body while sticking to A’s sword, and then you will return a stab toward A. Do this [back and forth] for a total of three times (circling with a full active grip) [tiger’s mouth facing to the right].

[photo for movement 1.17, showing B on the left, A on the right]

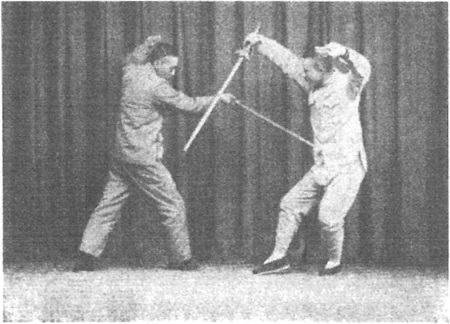

甲橫攪乙隨之――

[1.18] A, perform horizontal stirring [circling clockwise]. B, go along with it [counterclockwise].

甲俟乙劍刺來時,將劍粘住乙劍,向右向下橫攪之,

A, wait until B’s sword is stabbing toward you, then stick your sword to his and go to the right and downward with horizontal stirring.

[photo for the first part of movement 1.18, showing B on the left, A on the right]

同時舉右足交步向左繞走乙隨之亦交步向左繞走,斯時兩劍相粘不離,隨攪隨走,各俟機會,但攪時各伸出右手,左手戟指置於左方,平掌向外,頭向右轉,目視敵劍。

At the same time, lift your right foot into a crossover step and do a circle walk to the left [i.e. counterclockwise]. B, also do a crossover step and circle walk to the left. At this time, both swords are sticking to each other, stirring while walking, both of you waiting for an opportunity. But while stirring, your right hand stays extended, your left hand’s spearing finger placed level toward the left, palm facing outward, your head turned to the right, your gaze toward your opponent’s sword.

乙擊頭――

[1.19] B, strike to the head.

如前繞走,彼此互換位置時兩劍尖已第二次互攪至下方,乙劍正換至甲劍外方,甲劍正向上攪乙趁勢以少陽劍擊甲之頭。

Once both of you have switched places in your circle walk, your sword tip has completed two downward stirs. B, when your sword has been moved to the outside [inside] of A’s sword and A’s sword is about to stir upward again, take advantage of the opportunity to use a one-quarter active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the upper right] and strike [leftward] to his head.

甲擊腿――

[1.20] A, strike to B’s thigh.

身微向左後披重點寄於左足,成左實右虛弓步,避過乙劍,同時右手變太陰劍,斬擊乙之右腿。

Your body slightly drapes to the left rear, the weight shifting to your left foot, making a bow stance of left foot full, right foot empty, in order to evade B’s sword. At the same time, your right hand switches to a full passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the left] and does a slashing strike [rightward] to B’s right thigh.

乙截腕――

[1.21] B, check to A’s wrist.

體重寄於左足,舉右足向左前方斜進半步,避去甲劍,同時右手變為太陰劍斜截甲腕。

The weight shifting to your left foot, raise your right foot and advance a half step diagonally to the forward left, evading A’s sword, while your right hand switches to a full passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the left] and does a diagonal checking action to A’s wrist.

甲帶腕――

[1.22] A, do a dragging cut to B’s wrist.

右手變為太陽,往左肩前帶避,劍尖向敵方劍把,較肩略低,目注敵人。

Switch to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] and drag evasively toward the left until in front of your left shoulder, your sword tip now pointed toward B’s grip, slightly lower than shoulder level. Your gaze is toward B.

乙上步截腕――

[1.23] B, step forward and check to A’s wrist.

右足向右斜方趕上一步,右手用中陰劍,截敵右腕,重心移於右足,成右實左虛弓步。

Step your right foot forward diagonally to the right, and with your right hand using a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward], check to A’s right wrist, the weight shifting to your right foot, making a bow stance of right foot full, left foot empty.

甲抽手――

[1.24] A, do a drawing cut to B’s hand.

將腕往下一沈,避去乙劍,同時右手變為老陰劍,從左向右抽乙握劍之手。

Sink your right wrist downward to evade B’s sword, at the same time switching to a three-quarter passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the lower left], and go from left to right with a drawing cut to B’s hand.

乙抽避甲刺腹――

[1.25] B, withdraw to evade. A, stab to his belly.

趁乙抽劍避開之時,用中陰劍直刺乙腹,斯時體重移於右足。

A, as B draws back his sword to evade, take advantage of the moment by using a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to do a vertical-blade stab to his belly, your weight now shifting to your right foot.

乙截腕――

[1.26] B, do a [left] check to A’s wrist.

身微側讓去敵劍,右手用中陰劍橫截敵腕,斯時體重寄於右足。

With your body slightly leaning to the side to evade A’s sword, your right hand uses a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to check across his wrist, your weight now shifting to your right foot.

[photo for movements 1.25 & 1.26, showing A on the left, B on the right]

甲帶乙反格――

[1.27] A, drag. B, do an overturned block.

甲用太陽劍姿勢,將右腕往左前方一帶避開,同時收回右足移向左斜方半步,身半向左:目視敵方,乙劍跟隨敵腕由下往上反格,中陽。

A, using a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right], drag your right wrist evasively to the forward left [left rear]. At the same time, withdraw your right foot a half step diagonally to the left, your body turned halfway to the left, your gaze toward your opponent. B, your sword follows A’s wrist upward from below to do an overturned block using a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward].

甲抽腕保門――

[1.28] A, do a drawing cut to B’s wrist to get into the “guarding the gate” posture.

將右腕往上一翻,變為太陰劍,同時劍尖向下由左往右抽乙之腕,退步(右足往後退一步)轉身,斯時右手微屈高舉在右額前,成中陽劍,劍尖向敵,左手戟指扶住右腕,身體向右,體重寄於右足,左足置於右足左前方半步,足尖點地,目注敵方。

Your right wrist goes upward, turning over and switching to a full passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the left], and your sword tip, now angled downward, does a drawing cut to B’s wrist, from left to right, as you retreat your right foot a step, turning your body. Your right hand, arm slightly bent, is now raised up in front of the right side of your forehead in a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward], your sword tip pointing toward B. Your left hand’s spearing finger is assisting at your right wrist. Your body is turned to the right, the weight shifted to your right foot. Your left foot is placed a half step in front of your right foot to the forward left, toes touching down. Your gaze is toward B.

[photo for second part of movement 1.27 and movement 1.28, showing B on the left, A on the right (reverse view)]

乙帶腕保門――

[1.29] B, do a dragging cut to A’s wrist, then get into the “guarding the gate” posture.

乙劍變為太陽,往左帶敵之腕,同時收右足至左足前方半步,然後變為中陽劍,右足往右後方退一步立定,成保門姿勢。

B, switch to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] and go to the left with a dragging cut to [the inside] of A’s wrist, at the same time withdrawing your right foot until a half step in front of your left foot. [Although the photo above depicts A finishing his drawing cut while B is still in his blocking position, the dragging cut described here will happen as A is beginning his drawing cut and the swords will then be pulling away from each other at the same time.] Then switch to a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward], retreat your right foot a step to the right rear, and stand firmly on it, making the “guarding the gate” posture.

[This guarding posture is perhaps best exhibited in the photo that goes with the first movement of Section Four, by B on the left side of the photo.]

(完)

(This completes Section One [which has a total of twenty-nine movements and is comprised of twenty-two different techniques].)

–

第二路

SECTION TWO

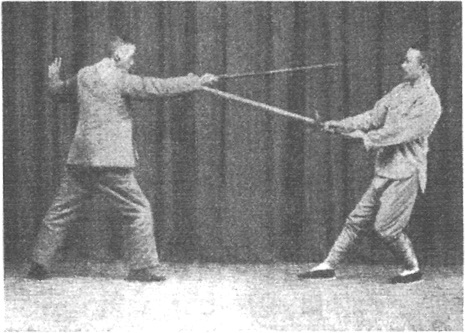

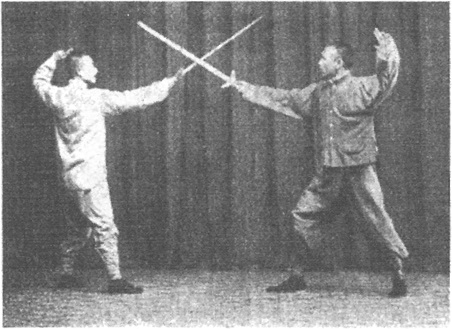

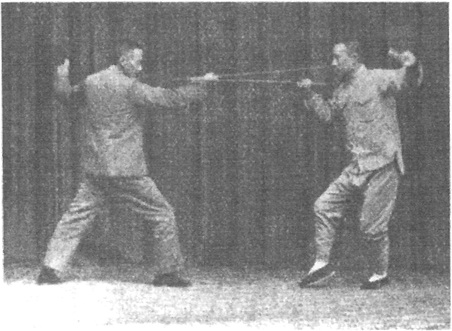

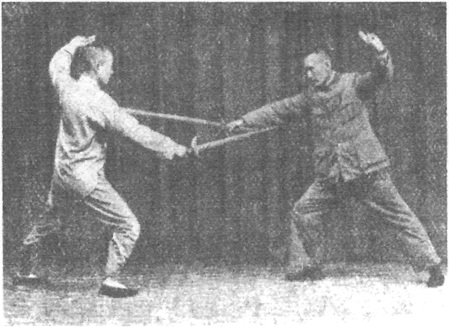

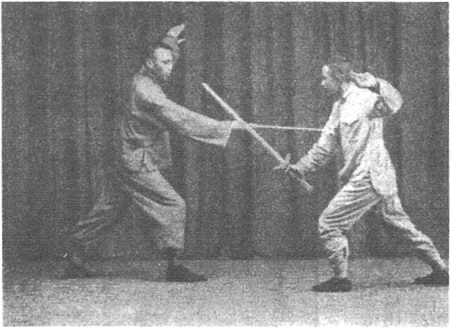

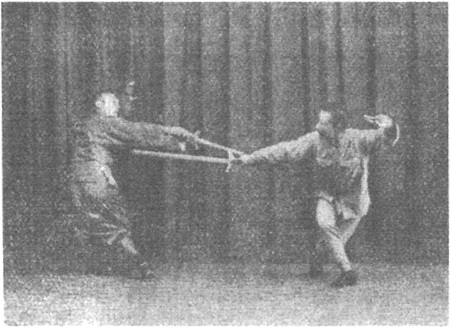

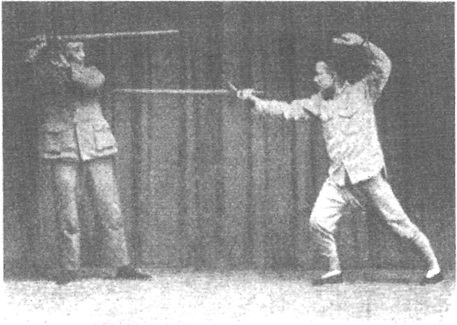

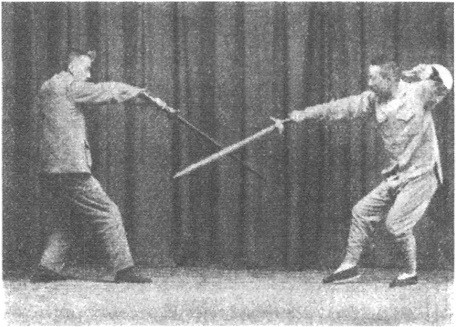

乙上步擊頂――

[2.1] B, step forward and strike to A’s head.

右足前進一步,同時右手以少陽劍擊甲之左頂,左手分開置於左後方。

Advance a step with your right foot as your right hand uses a one-quarter active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the upper right] to do a [leftward] striking action to the left side of A’s head, your left hand spreading away to the left rear.

甲上步擊腕――

[2.2] A, step forward and strike to B’s wrist.

右足前進一步,同時右手用太陽劍擊乙之腕,左手分開置於左後方。

Advance a step with your right foot as your right hand uses a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] to do a [leftward] striking action to B’s wrist, your left hand also spreading away to the left rear.

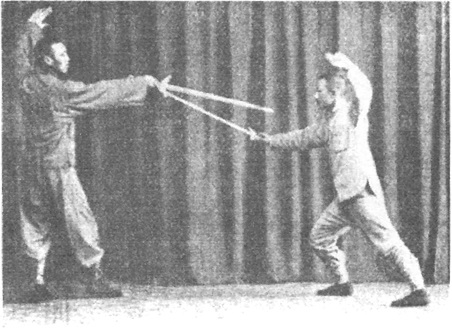

[photo for movements 2.1 & 2.2, showing A on the left, B on the right]

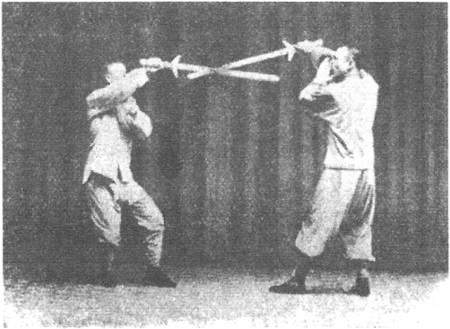

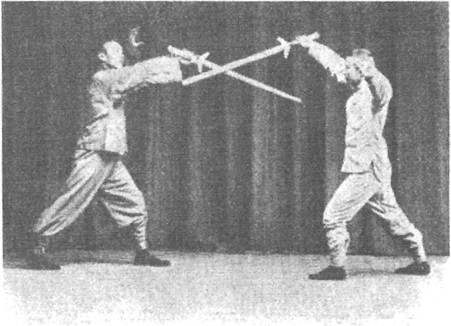

甲乙對提――

[2.3] Both of you, make a lifting posture.

乙先提,甲隨之式如前。

B lifts first, then A, same as before [movement 1.14].

[photo for movement 2.3, showing A on the left, B on the right]

甲乙對刺膝――

[2.4] Both of you, stab to the knee.

各將右足微起用左足着力一蹬,箭步前進,刺敵之膝,但兩劍相拒,各刺不中(此時另有動作須面授)。

Both of you slightly lift your right foot, pressing the ground with your left foot, and advance into a bow and arrow stance, stabbing to your opponent’s knee. But because your swords are resisting against each other, the stabs go off center. (The rest of the movement at this point requires personal instruction.) [This is perhaps referring to the tighter way the two people are walking around each other rather than normal circle walking.]

甲乙各上步反繃――

[2.5] Both of you, step forward and do an overturned flick.

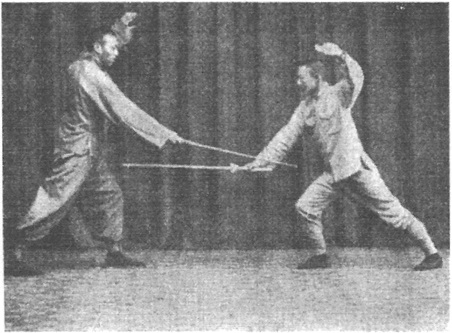

當刺不中,彼此挨身而過時,各將劍變為中陰,竭力使用劍身粘住敵劍,(防其趁勢而入帶腰或帶腿也)斯時雙方各將左足前進一步,披身下挫,同時以中陽劍反繃敵腕。

When your stabs miss, both of you wait for the other’s body to go past, then switch your grip to half passive [tiger’s mouth facing upward], deliberately sticking your sword body to the other sword (thereby preventing him from taking advantage of the opportunity to come in with a dragging cut to your waist or thigh). Then both of you advance your left foot a step forward [behind your right leg], draping your body by bending forward, while using a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward] to do a reverse flick toward your opponent’s wrist.

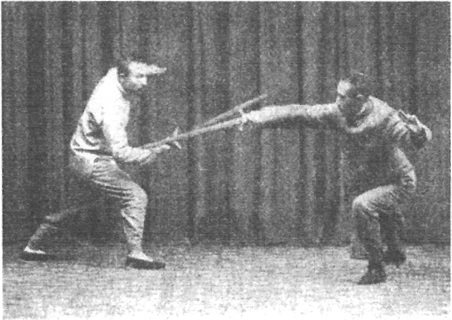

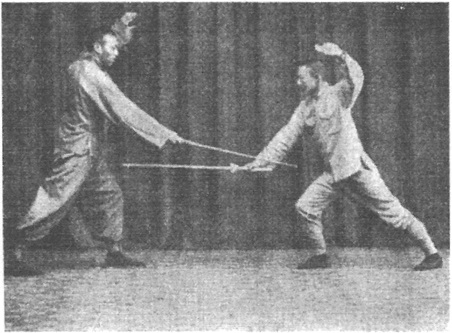

[photo for movement 2.5, showing B on the left, A on the right]

甲轉身點腕――

[2.6] A, turn your body and tap to B’s wrist.

以左足着地迅速轉身起立,收回右足,成預備步,同時以中陰劍點敵之腕。

Pivoting [withdrawing] your left foot, quickly turn your body and stand up, withdrawing [putting out] your right foot, the same as in the preparation posture, and at the same time use a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to tap toward B’s wrist.

[photo for movement 2.6, showing A on the left, B on the right (reverse view)]

乙轉身斜步繃腕――

[2.7] B, turning your body, step diagonally, and flick to A’s wrist.

迅速轉身起立,以右足着地,左足隨卽向左側方移進一步,收回右足,成預備步,身向下沈左手扶住劍柄,同時劍尖向上斜繃敵腕。

Pivoting on your right foot, quickly turn and stand up, advancing your left foot a step to the left side and withdrawing your right foot to stand the same as in the preparation posture. [The text is therefore calling for an empty stance rather than the bow stance in the photo, which would make sense considering that B will have to step forward into a right bow stance in his next movement.] With your body sinking down and your left hand assisting at your sword handle, flick your sword tip diagonally upward toward A’s wrist.

[photo for movement 2.7, showing A on the left, B on the right (reverse view)]

甲抽――

[2.8] A, do a drawing cut.

將腕往右外避去乙劍,右腕下沉抽乙握劍手,同時右足向右前斜方跨出半步,重心在右足。

Send your wrist outward to the right to evade B’s sword, then sink your right wrist into a drawing cut to B’s sword hand, at the same time stepping your right foot out diagonally a half step to the forward right, the weight going onto your right foot.

乙刺腹――

[2.9] B, stab to A’s belly.

趁甲抽劍避開之時,用中陰劍直刺甲腹,同時右足向右前斜移半步,重心寄于右足。

When A evades by doing a drawing cut, [draw back your sword and then] use a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to do a vertical-blade stab to his belly, at the same time shifting your right foot diagonally a half step to the forward right, the weight going onto your right foot.

甲左截腕――

[2.10] A, do a left check to B’s wrist.

俟乙劍刺腹時,將身略偏避去乙劍,同時右手以中陰劍向前截乙執劍之手,重心仍在右足。

Wait for B’s sword to be stabbing toward your belly, then slightly lean away to evade his sword, at the same time using a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to go forward to his hand with a checking action, the weight still on your right foot.

[photo for movements 2.9 & 2.10, showing B on the left, A on the right]

乙劈甲亦劈――

[2.11] B chops and A also chops.

如前對劈之式。

Same as before [movement 1.15].

乙上步貫耳――

[2.12] B, step forward and perform “filling the ear”.

右手變為太陽劍,左手扶住劍柄,上右足探身伸劍貫敵右耳。

Switch to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right], and with your left hand assisting at your sword handle [although it is raised to the left in the photo], step your right foot forward, reach with your body, and extend your sword in a [rightward] strike to A’s right ear.

甲平帶――

[2.13] A, do a horizontal dragging cut.

右手用太陽劍,垂肘轉腰,同時將劍往右後方平帶乙腕,格開乙劍。

With your right hand using a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right], drop your elbow and turn your waist, at the same time sending your sword to the right rear in a horizontal dragging cut [using the inner edge] to B’s wrist, thereby blocking his sword aside.

[photo for movements 2.12 & 2.13, showing B on the left, A on the right]

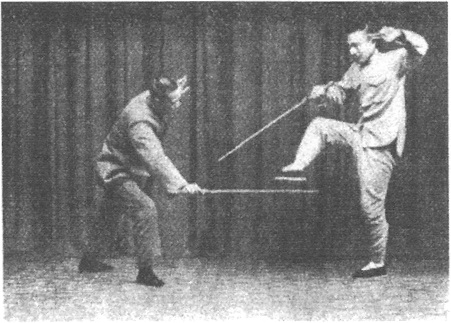

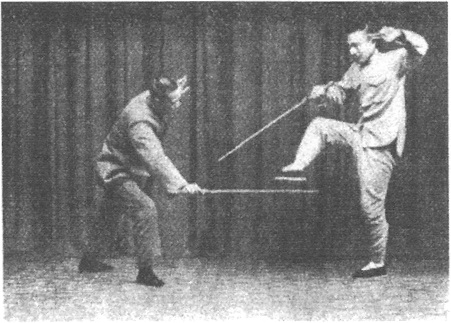

乙抽腿――

[2.14] B, do a drawing cut to A’s leg.

趁勢將劍一翻,變為太陰,轉身抽甲之腿。

Take advantage of the opportunity to turn your sword over, switching to a full passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the left], and turn your body [with your right foot stepping to the forward right] as you do a drawing cut to A’s leg.

甲刺腕――

[2.15] A, stab to B’s wrist.

向左斜方舉起右腿,避去乙劍,同時右手將劍尖指敵右腕刺去。

Lift your right leg diagonally to the left to evade B’s sword, then your right hand points your sword tip toward his right wrist and stabs.

[photo for movements 2.14 & 2.15, showing B on the left, A on the right]

[Huang had another photo made of this situation, appearing in his 1936 book, showing Ye Jingcheng on the left in the role of B, Huang Yuanxiu again on the right in the role of A.]

乙退步繞避,甲進步追刺――

[2.16] B retreats with an evasive arc as A advances with a chasing stab.

乙向右退步繞避,甲向左進步繞追,雙方各循半圓形之弧線進退。

B, retreat to the right, making an evasive arc, as A advances to the left, making a chasing arc. Both of you are performing your retreat and advance [with your feet] while drawing a half circle [with your swords].

甲抽腹乙含胸轉腰刺腕――

[2.17] A, do a drawing cut to B’s belly. B, hollow your chest, turn your waist, and stab toward A’s wrist.

甲進至中圓形弧線將終點時,將劍轉為太陰,抽乙之腹,

A, advance until you reach the full extent of the arc you are drawing, then turn your grip to full passive [tiger’s mouth facing to the left] and do a drawing cut to B’s belly.

[photo for movement 2.16 and the first part of movement 2.17, showing B on the left, A on the right]

乙卽含胸轉腰避去甲劍,同時將己劍轉為太陽,刺甲之腕。

B, hollow your chest and turn your waist to evade A’s sword, at the same time switching to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] and doing a [horizontal-blade] stab toward his wrist.

甲退步繞避乙進步追刺――

[2.18] A retreats with an evasive arc as B advances with a chasing stab.

甲亦向右循半圓形弧線退步繞避,乙進步繞追,如是三遍。

A, it is now your turn to retreat, stepping to the right, as you make an evasive arc, while B chases [stepping to the left], making a chasing arc, and thereby you are both drawing the other half of the circle. Do this for a total of three times [i.e. drawing three full circles].

乙壓劍上步擊頂――

[2.19] B, press down A’s sword, then step forward and strike to his head.

乙繞退將至終點時,突然止步將劍變為太陽,微抬其腕,讓甲劍從腕下刺過,趁勢將甲劍壓格於外方,隨卽上步擊甲之左頂。

B, when your circling retreat has brought you back to where you started, suddenly stop, turning your sword to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] and slightly raising your wrist to allow A’s sword to stab under it, then take advantage of the opportunity by pressing down A’s sword and block it outward. Then step forward with a [leftward] strike to the left side of A’s head.

甲退步帶腕上步回擊――

[2.20] A, retreat with a dragging [drawing] cut to B’s wrist, then step forward, returning a strike.

退步避過乙劍,同時將劍往右外方平帶,

Retreat to evade B’s sword while sending your sword outward to the right with a horizontal dragging [drawing] cut.

[photo for the second part of movement 2.19 and the first part of movement 2.20, showing B on the left, A on the right]

復趁勢上步回擊乙之左頂。

Then take advantage of the opportunity to step forward and return a [leftward] strike to the left side of B’s head.

乙退步抽腕保門――

[2.21] B, retreat with a drawing cut to A’s wrist, both of you returning to the guarding posture.

俟甲伸劍進擊,轉為中陽劍,從下方抽甲之腕,同時右足退一步保門。甲退步保門。

Wait for A to reach out with his sword, advancing to strike, then turn your sword to a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward] and go from below with a drawing cut to A’s wrist. At the same time, retreat your right foot a step, returning you to the guarding posture, and then A also retreats to return to the guarding posture.

[The 1931 book replaces B’s drawing cut with both people getting into a lifting posture as a means to return to the guarding posture. The accompanying photo shows both people pulling back from lifting, but already retreated into the guarding posture in terms of their feet. The result is that they are standing in this image much closer than they would be, a similar situation to the photo for movement 1.3, possibly indicating in both cases that the photographer may have had a cramped studio and could not widen the frame enough to have two people standing very far apart.]

(完)共十九式不同者十式

(This completes Section Two, which has a total of nineteen [twenty-one] movements and is comprised of ten different techniques.)

–

第三路

SECTION THREE

乙上步劈頂――

[3.1] B, step forward, chopping to A’s head.

右足上步,右手用中陰劍,正劈甲頂。

Step forward with your right foot, your right hand using a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to do a chop straight to A’s head.

甲格劍進步翻身帶腰――

[3.2] A, block B’s sword, advance, turning your body, and do a dragging cut to B’s waist.

上右足,用中陽劍格,

Step forward with your right foot, using a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward] to block to B’s sword.

[photo for movement 3.1 and the first part of movement 3.2, showing A on the left, B on the right (reverse view)]

隨卽向左前方進左足,復交步上右足,右手將劍轉為太陽,帶乙之腰。

Quickly advance your left foot to the forward left, then your right foot will step forward with a crossover step, your right hand turning your sword over into a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right], and do a dragging cut to B’s waist.

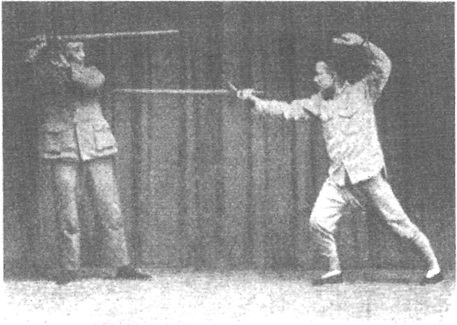

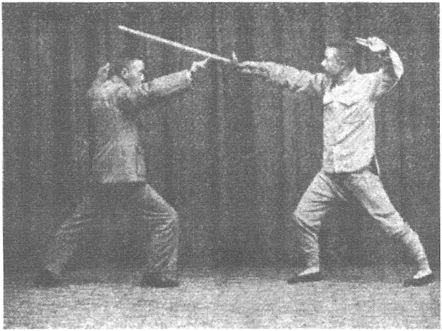

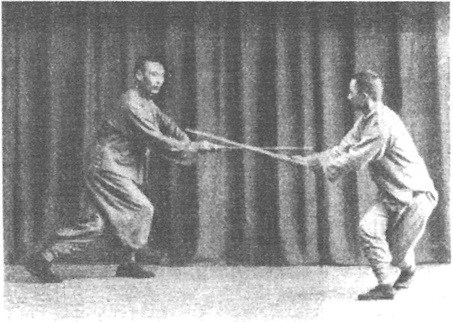

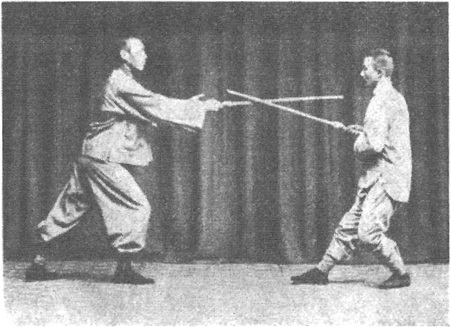

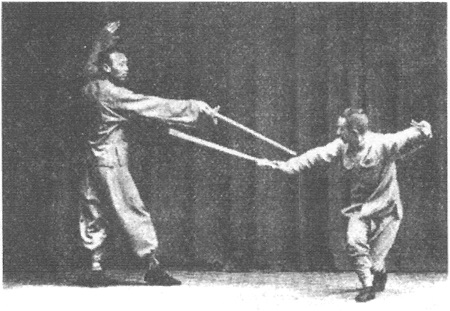

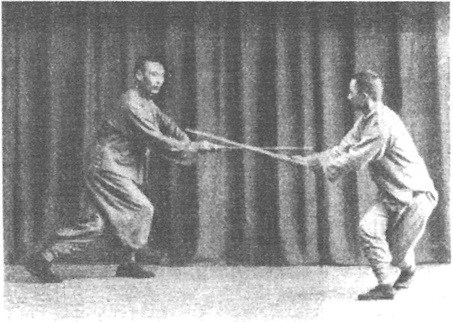

乙格腕帶腰――

[3.3] B, block to A’s wrist, then do a dragging cut to his waist.

一面含胸轉身,退右足避過敵劍,一面將劍尖下指,右腕上提,從左往右外方格甲之腕,

Hollowing your chest and twisting your body, retreat your right foot to evade A’s sword. At the same time, point your sword tip downward, lifting your right wrist, and go outward from left to right with an [overturned] block to A’s wrist.

[photo for the second part of movement 3.2 and the first part of movement 3.3, showing A on the left, B on the right (reverse view)]

甲旣翻身避去,乙迅速向左前方進左足,復交步上右足,亦將劍變為太陽帶甲之腰。

A will twist his body away to evade this, so quickly advance your left foot to the forward left, step your right foot forward with a crossover step, and change your grip to full active [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] as you do a dragging cut to his waist.

甲格腕帶腰――

[3.4] A, block to B’s wrist and drag to his waist.

亦如乙之動作,如是互換繞走數遍。

This is the same as B’s movement. Circle walk [counterclockwise] in this manner, repeating the movement a number of times until you have switched places.

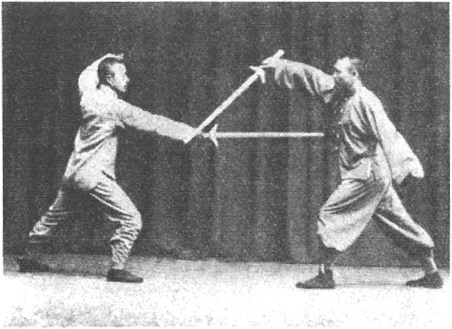

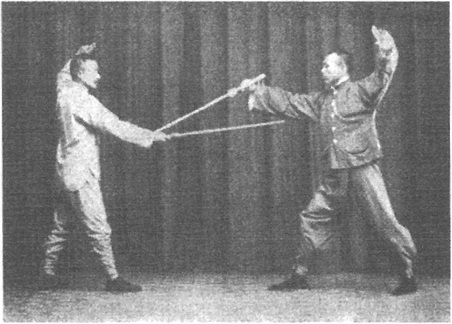

乙壓劍貫耳――

[3.5] B, press down A’s sword and perform “filling the ear”.

俟甲劍轉為太陽,尚未進步帶腰之際,用中陰劍往下擊壓,

Wait for A to turn his sword to the full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right], and in the moment before he has advanced to drag to your waist, use a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to hit downward with a pressing action.

[photo for the first part of movement 3.5, showing A on the left, B on the right]

隨卽起身上步,用太陽劍貫甲右耳。

Then raise your body and step forward, using a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] to strike [rightward] to his right ear.

甲直帶繃――

[3.6] A, do a [vertical-blade] dragging cut with a flicking energy.

起身微向後挫,用中陰劍直帶兼繃敵之腕。

Raise your body and slightly sit back, using a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to do a vertical-blade dragging cut, flicking toward B’s wrist.

[photo for the second part of movement 3.5 and movement 3.6, showing A on the left, B on the right]

乙提――

[3.7] B, make a lifting posture.

如以前式,提劍刺敵之腕。

As performed previously [movement 1.14], make a lifting posture, stabbing toward A’s wrist.

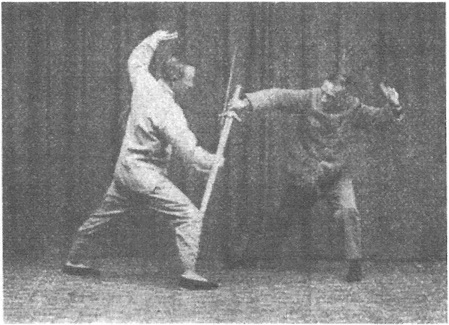

甲反擊腕――

[3.8] A, do a reverse strike toward B’s wrist.

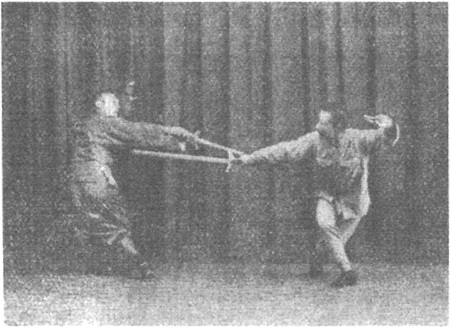

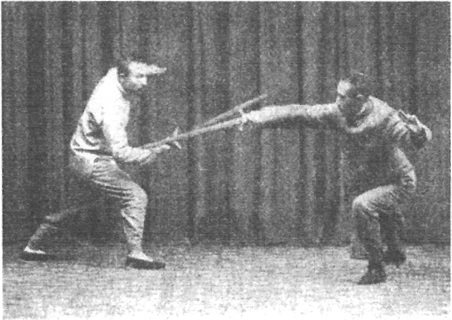

右足向左方交進一步,身向下蹲,同時將劍從左下方繞一圓圈,側面反擊敵之右腕,左手扶住劍柄,頭向右轉,目注敵右腕。

Advance your right foot with a crossover step to the left and squat your body down, at the same time sending your sword downward to the left and circling back up from the side with a reverse strike [i.e. rightward] toward B’s right wrist, your left hand assisting at your sword handle, your head turning to the right, your gaze going toward B’s right wrist.

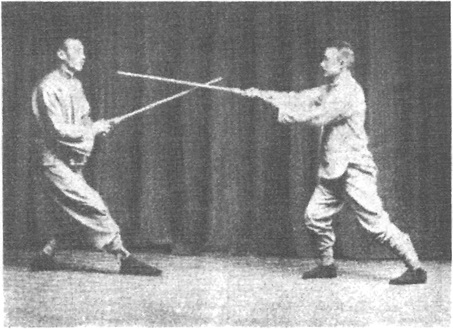

乙反擊腕――

[3.9] B, do a reverse strike toward A’s wrist.

亦用甲同樣動作姿勢反擊。

Do the same movement as A, also making a reverse strike toward his wrist.

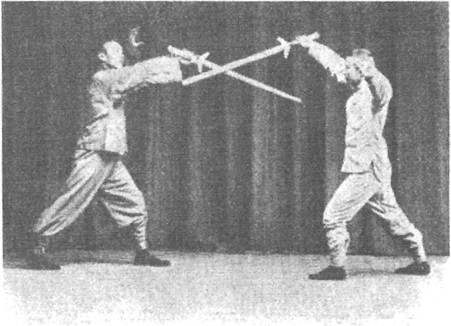

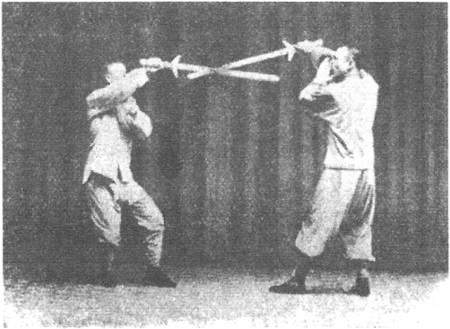

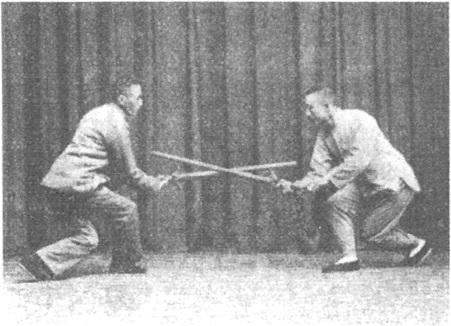

[photo for movements 3.8 & 3.9, showing A on the left, B on the right]

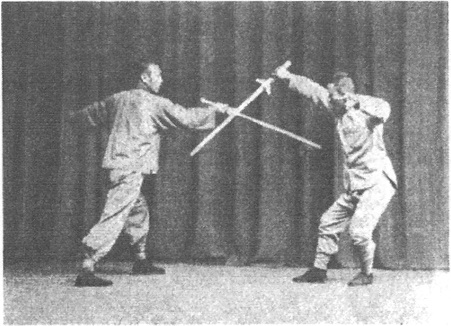

對繞走――

[3.10] Both of you, circle walk.

甲乙兩劍尖各指敵腕,蹲身繞走,從左方向右繞走,至互換位置時停止。

With both of you using your sword tip to point toward the other’s wrist, squat your body and walk in a rightward [counterclockwise] circle until you have switched places.

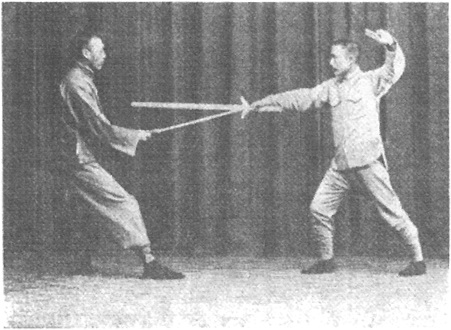

乙抽劍刺――

[3.11] B, withdraw your sword, then stab.

突然抽劍向後變為中陰劍直刺,同時右足開一步向右。

Suddenly withdraw your sword to the rear, changing to a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward], then do a vertical-blade stab, at the same time stepping your right foot out to the right.

甲反格腕――

[3.12] A, do a reverse block to B’s wrist.

抽劍向後,同時右足開一步向右,用中陰劍,從敵腕下反格之。

Withdraw your sword to the rear, at the same time stepping your right foot out to the right, and use a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to do a reverse block under B’s wrist.

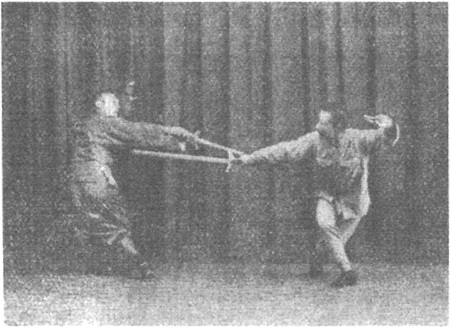

[photo for movements 3.11 & 3.12, showing A on the left, B on the right (reverse view)]

乙直帶腕――

[3.13] B, do a vertical-blade dragging cut to A’s wrist.

微抬其腕,劍尖向下交敵之腕,隨卽將腕往下一沈,向後抽帶。

Slightly raise your wrist so your sword tip angles downward and crosses over A’s wrist, then sink your wrist downward and withdraw to the rear with a dragging cut.

甲反手帶腕――

[3.14] A, turn your hand over and do a dragging cut to B’s wrist.

甲將肘往下往左避去敵劍,同時反腕,成中陽劍,抽帶敵腕。各退步保門。

A, send your elbow downward to the left to evade B’s sword, at the same time turning your wrist to make a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward], and withdraw with a dragging cut to B’s wrist [using the inner edge]. Then you both retreat to the guarding posture.

(完)其計十五式不同者六式

(This completes Section Three, which has a total of fifteen [fourteen] movements and is comprised of six different techniques.)

–

第四路

SECTION FOUR

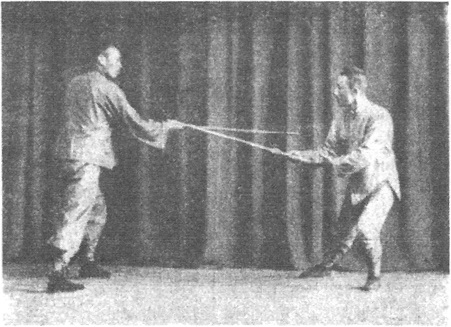

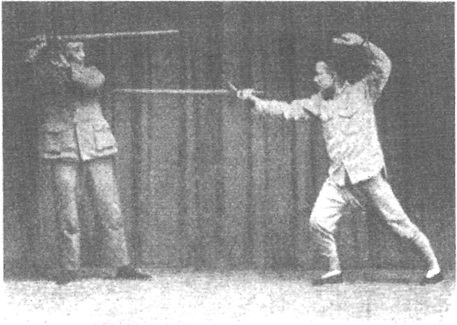

甲上步洗――

[4.1] A, step forward and do a clearing cut.

右足前進一大步,右手執劍從右下方往上洗,變為中陽劍,伸直右臂左手戟指,置於左後方,兩足成右實左虛弓步,目視敵方。

Advance your right foot a large step, your right hand sending your sword clearing upward from the lower right, switching to a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward], your right arm reaching, your left hand’s spearing finger placed to the left rear, your feet making a bow stance of right foot full, left foot empty. Your gaze is toward the opponent.

[photo for movements 4.1, showing B on the left, A on the right]

乙上步帶腕(陽劍圈起手式)――

[4.2] B, step forward and do a dragging cut to A’s wrist (circling your sword to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] with your hand lifted).

右足向左前方側進一步,身體微蹲,右手執劍,從右上方經右下方向左前方復轉右前方,畫一螺旋形反帶甲之右腕,斯時變成太陽劍,伸直右臂,左手同時扶住劍柄,頭半向右轉,目注敵腕,兩足成交步。

Advance your right foot a step to the forward left, slightly squatting your body, as your right hand draws a circle with your sword from the upper right to the lower right to the forward left, then again to the forward right to finish the circle with a reverse [i.e. inner edge] dragging cut toward A’s right wrist. Your grip has now switched to full active [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] and your right arm is extended. Your left hand at the same time assists at your sword handle. Your head is turned halfway to the right, your gaze toward A’s wrist. Your feet are making a crossover stance.

甲上步帶腕(陽劍圈起手式)――

[4.3] A, step forward and do a dragging cut to B’s wrist (circling your sword to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] with your hand lifted).

亦如乙之動作姿勢,反帶乙腕。

Mirror B’s movement by [stepping your right foot out to the left and] doing a reverse dragging cut toward his wrist.

[photo for movements 4.2 & 4.3, showing B on the left, A on the right]

對陽劍圈――

[4.4] Both of you, make circles with full active grips [tiger’s mouth facing to the right].

甲乙各先進左足,同時將劍往自己懷中帶回,

Both of you advance first your left foot while withdrawing your sword with a [reverse] dragging cut.

[photo for the first part of movement 4.4, showing B on the left, A on the right]

次進右足,同時將劍由左往右平走一圓圈,反帶敵腕,如是繞走三遍。

Then advance your right foot while again sending your sword across from left to right. Continue into a [counterclockwise] circle walk while doing these reverse dragging cuts toward your opponent’s wrist, walking in this way as your swords make a total of three circles.

對陰劍圈――

[4.5] Both of you, make circles with full passive grips [tiger’s mouth facing to the left].

甲乙各將劍變為太陰,同時開右足向右側方探步,一面繞走,一面抽敵腕與敵腹,如是繞走三遍。

Both of you switch your sword to a full passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the left] while stepping your right foot out to the right side in a reaching step, then continue into a [clockwise] circle walk as you each do [reverse (i.e. inner edge)] drawing cuts [moving from right to left] toward the other’s wrist or belly, walking in this way as your swords make a total of three circles.

乙進步攪――

[4.6] B, advance with [vertical] stirring.

如前繞走至終圈時,突然將劍往胸前收回,變為太陽劍,劍尖從右往左(在敵腕上)

Once you have circle walked back to where you started, suddenly withdraw your sword in front of your chest, changing to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right], and your sword tip goes from right to left (over A’s wrist).

[photo for the first part of movement 4.6, showing B on the left, A on the right]

復從左往右(在敵腕下)繞攪敵腕,

Then your sword tip goes from left to right (under A’s wrist), stirring a full [counterclockwise] circle around his wrist.

[photo for the second part of movement 4.6, showing B on the left, A on the right]

一面逐步前進,左手扶住劍柄,此動作全在腰腿手腕一致敏活,否則難以得勁勢矣。

While stirring, you are also chasing forward [though the photos do not really seem to demonstrate any stepping] and your left hand is assisting at your sword handle. This [stirring] movement entirely comes from the liveliness of your hips and wrist, otherwise it is difficult to get the energy of it.

甲退步攪――

[4.7] A, retreat with [vertical] stirring.

甲亦如乙之動作,但隨乙之進逼,逐步後退,(進退之步法須四平步挫腰)。

A, this is the same as B’s movement, but while B is advancing, you are retreating [and your stirring is instead making a clockwise circle]. (The advancing and retreating steps should be coordinated with folding in at the waist [indicating that the opposite hip is coming forward with each step, thus bringing your sword handle across your body as you go].)

乙退步抽帶――

[4.8] B, retreat with drawing and dragging.

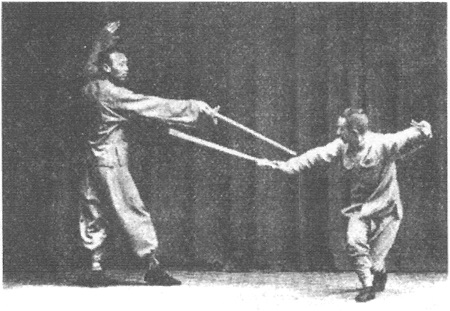

用太陰太陽劍,從敵腕下方抽帶,一面逐步後退,(此式如太極劍中之獅子搖頭)。

Using both the full passive [tiger’s mouth facing to the left] and full active [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] grips, draw and drag under A’s wrist while retreating. (This is the same technique as Taiji Sword’s LION SHAKES ITS HEAD.)

甲進步抽帶――

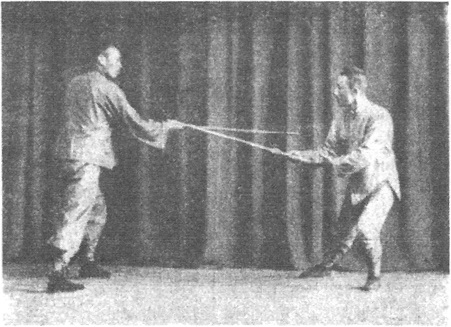

[4.9] A, advance with drawing and dragging.

亦用太陽太陰劍,從敵腕上方抽帶,但甲用抽,則乙用帶,適與相反,一面逐步前進。

Using both the full active [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] and full passive [tiger’s mouth facing to the left] grips, draw and drag on top of A’s wrist while advancing. While you are drawing, B is dragging, and so you should be doing the opposite of each other.

[photos for movements 4.8 & 4.9, showing B on the left, A on the right]

乙繃腕――

[4.10] B, do a flick to A’s wrist.

退回原位置時,突然用中陰劍上繃甲腕。甲抽劍避之。兩手相左右分開。

When you have retreated to your original position, suddenly use a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to flick upward toward A’s wrist. A will withdraw his sword to evade it by spreading his hands apart to the sides.

乙上步刺頭――

[4.11] B, step forward and stab to A’s head.

斯時見敵方正面無備,上步用中陰劍直刺其面。

Noticing that A is now unguarded in front, step forward and use a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to do a vertical-blade stab to his face.

甲壓劍――

[4.12] A, press down B’s sword.

將頭向左側一偏,避過敵劍,同時右手將劍壓住敵劍,向右下方,兩足須左實右虛。

Lean your head away to the left to evade B’s sword, your right hand at the same time sending your sword to press B’s sword to the lower right. Your feet should be left foot full, right foot empty.

乙反壓――

[4.13] B, do a counter press.

將敵劍反壓於左下方,兩足須左實右虛。

Send A’s sword to the lower left with a counter press. Your feet should be left foot full, right foot empty.

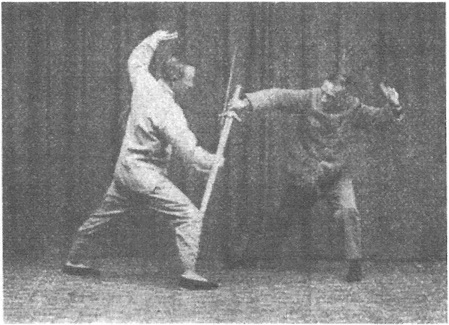

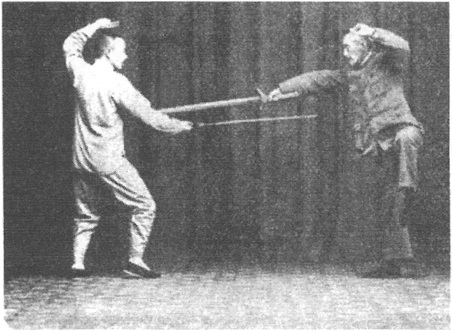

甲帶腿――

[4.14] A, do a dragging cut to B’s leg.

趁我劍被壓時,進劍帶敵之右腿,隨卽起身,將劍反擊敵之右耳,伸直右手,兩足右實左虛弓步。

Go along with being pressed down by advancing your sword into a dragging cut to B’s right leg. [B of course lifts his leg to evade this and then puts it down again.] Then raise up your body and do a reverse strike to B’s right ear, straightening your right arm. Your feet are in a bow stance of right foot full, left foot empty.

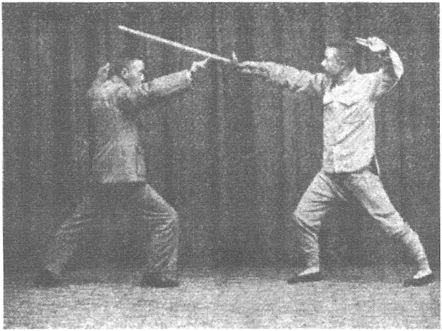

乙直帶兼繃。――

[4.15] B, do a vertical-blade dragging cut with a flicking energy.

身體微向後傾,同時用中陰劍,由前向後直帶敵腕,終仍變為繃式。

Your body slightly leans back as you use a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to pull back with a vertical-blade dragging cut to A’s wrist, finishing as a flicking action.

[photo for the second part of movement 4.14 and movement 4.15, showing B on the left, A on the right]

[Although the 1931 book suggests using this variant version at this point in the set, emphasizing the vertical-blade dragging more than the flicking, the text here does not indicate that this situation is substantially different from what is described in movements 1.13 and 3.6, and so the earlier photo would seem to work just as well.]

甲乙各提劍保門――

[4.16] Both of you, make a lifting posture, then return to the guarding posture.

甲先變為提,乙隨之。

A first switches to lifting, then B.

[photo for the first part of movement 4.16, showing B on the left, A on the right]

(完)共計十七式不同者十式

(This completes Section Four, which has a total of seventeen [sixteen] movements and is comprised of ten different techniques.)

–

第五路上

SECTION FIVE – Part 1

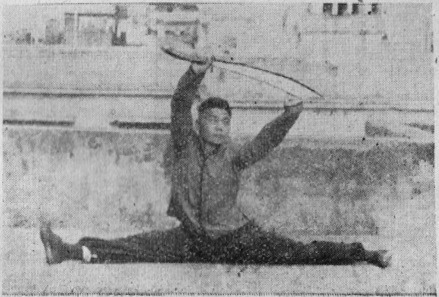

甲乙各作伏勢――

[5.1] Both of you, get into a crouching posture.

身向右後方下披,重點寄於右足,伸直左腿,近貼地面,右手變為太陽劍,橫於胸前,劍尖向敵,左手戟指扶右手之腕,目視敵方。

Your body goes to the right rear and drapes downward, the weight shifting onto your right foot, your left leg straightening and almost touching the ground, as your right hand switches to a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] and holds your sword across the front of your chest, the tip pointing toward the opponent, your left hand’s spearing finger assisting at your right wrist. Your gaze is toward the opponent.

甲上步直刺――

[5.2] A, step forward and do a vertical-blade stab.

聳身向前,右足前進一步,右手用中陰劍直刺敵胸。

Launch your body forward, your right foot advancing a step, as your right hand uses a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to do a vertical-blade stab to B’s chest.

乙上步擊腕――

[5.3] B, step forward and strike to A’s wrist.

聳身向前,右足前進一步,右手用太陽劍,平擊敵腕。

Launch your body forward, your right foot advancing a step, as your right hand uses a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] to strike across [leftward] to A’s wrist.

甲抬腕平擊腕――

[5.4] A, raise your wrist and strike across to B’s wrist.

抬高手腕避過敵劍,同時以太陽劍,平擊敵腕。

Raise up your wrist to evade B’s sword, at the same time using a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right] to strike across [leftward] to B’s wrist.

[photo for movements 5.3 & 5.4, showing B on the left, A on the right]

乙側身截腕――

[5.5] B, take your body to the side and check to A’s wrist.

左足向左側開進一步,成左實右虛弓步,體重寄於左足,同時右手用中陰劍,從敵之右前方,側截其腕。

Your left foot advances a step out to the left side, making a bow stance of left foot full, right foot empty, the weight shifting to your left foot. At the same time, your right hand uses a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to go to the forward right with a [right] check to A’s wrist from the side.

[photo for movement 5.5, showing A on the left, B on the right (reverse view)]

甲側身截腕――

[5.6] A, take your body to the side and check to B’s wrist.

亦如乙之動作姿勢。

Same as B’s movement and posture above.

對提對繞走――

[5.7] Both of you, make a lifting posture, then circle walk [counterclockwise].

此兩動作已見前第一路中。

These two actions are the same as in Section One [movements 1.7 & 1.8].

[photo for the first part of movement 5.7, showing B on the left, A on the right]

甲正繃腕――

[5.8] A, do an upright flick to B’s wrist.

繞走至互換位置時,突然轉為中陰劍,繃敵之腕,

Once you have walked around B to the point that you have switched places with him, suddenly switch to a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] and do a flick toward his wrist.

乙帶腕避――

[5.9] B, do a dragging cut to A’s wrist, dodging away.

向左帶腕,避去敵劍,身體同時半向左轉,體重寄於右足。成左實右虛弓步。

Go to the left with a dragging cut to A’s wrist, evading his sword by turning your body halfway to the left as the weight shifts to your right [left] foot, making a bow stance of left foot full, right foot empty.

甲進步反格腕――

[5.10] A, advance and do an overturned block to B’s wrist.

左足速進一步,同時以中陰劍,劍尖斜向下方如提劍式,左手扶住右腕,用力自下向上反格敵腕。

As your left foot quickly advances a step, use a half passive [half active] grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward] to point your sword tip diagonally downward, similar to the lifting posture, and with your left hand assisting at your right wrist, forcefully go upward from below with an overturned block to B’s wrist.

乙截腕――

[5.11] B, check to A’s wrist.

將右腕抬高,避去甲劍,從甲腕上繞過,用中陰劍截其腕,斯時體重移於右足,成右實左虛弓步。

Raise your right wrist up to avoid A’s sword, arcing over A’s wrist, then use a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to do a [left] check toward his wrist. At this moment, the weight is shifting to your right foot to make a bow stance of right foot full, left foot empty.

甲上步截腕――

[5.12] A, step forward and check to B’s wrist.

速離開左手,將右腕往右一移避過乙劍,同時右足前進一步,成右實左虛步,截敵之腕。

Quickly spreading away your left hand, send your right wrist to the right to evade B’s sword and do a [left] check to his wrist as you advance your right foot a step, making a bow stance of right foot full, left foot empty.

乙抽身截腕――

[5.13] B, withdraw and check to A’s wrist.

略移右腕,同時抬腕,劍尖向下截敵右腕外方,兩足變左實右虛。

Slightly shift your right wrist back, at the same time raising it so your sword tip is angled downward, and do a [reverse] check to the outside of A’s right wrist, your feet switching to left foot full, right foot empty.

[photo for movements 5.12 & 5.13, showing A on the left, B on the right]

甲壓腕(或作截腕)――

[5.14] A, press down B’s wrist (or check to his wrist).

將腕往左避開,同時將劍從敵腕上繞過,下壓敵腕,(用太陰劍若截則用中陰劍)斯時步法變為左實右虛。

Dodge your wrist to the left while arcing your sword over B’s wrist, then press down on his wrist. (If pressing, use a full passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the left]. If checking, use a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward].) [Since you just did a check and are already in that position, the press would seem to make more sense anyway.] At the same time, your stance switches to left foot full, right foot empty.

乙抽手截腕――

[5.15] B, withdraw your hand, then do a [left] check to A’s wrist.

仍如前式。

Same as before [movement 5.11].

甲帶腿――

[5.16] A, do a dragging cut to B’s leg.

斯時右腕旣被敵劍壓住,惟有趁勢從下往左帶敵之腿,同時體重移於左足,收回右足,移至左足前方半步,復趁勢刺敵之腰。

With your right wrist now being pressed [checked] by B’s sword, take advantage of the situation by going downward and to the left with a dragging cut to A’s leg, at the same time shifting your weight to your left foot and drawing in your right foot to be a half step in front of your left foot, then start to stab to B’s waist [which B beats you to by stabbing to your waist, and so your movement of raising your sword to stab will simply become the beginning of the action in movement in 5.18 of pulling your sword back].

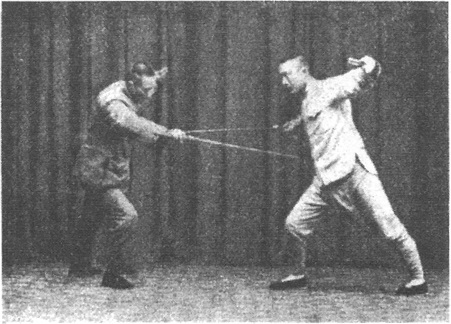

乙刺腰――

[5.17] B, stab to A’s waist.

蹺起右足,避過敵劍,迅速起立,將右足移至左足前方半步,身半向左,右手以中陰劍刺敵之右腰。

Raise your right foot to evade A’s sword, briefly standing on one leg, then shift your right foot to be a half step in front of your left foot, your body turning halfway to the left as your right hand uses a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to stab to the right side of A’s waist.

甲抽腕――

[5.18] A, do a drawing cut to B’s wrist.

抬高其腕,一面避去敵劍,一面以太陰劍抽敵之腕,同時收回右足,向右前方移一步。

Raise your wrist as you evade A’s sword and use a full passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the left] to do a drawing cut to his wrist. At the same time, withdraw your right foot and shift a step to the forward right [right rear].

乙金鷄獨立刺胸――

[5.19] B, perform GOLDEN ROOSTER STANDS ON ONE LEG to stab to A’s chest.

右手往左一帶,避去敵劍,隨卽以中陰劍,直刺敵胸,並提起左足,全身重點,寄於右足,作金鷄獨立式。

Your right hand goes to the left with a dragging action to evade A’s sword, then uses a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to do a vertical-blade stab to his chest. At the same time, lift your left foot, the weight of your whole body shifted onto your right foot, making the posture of GOLDEN ROOSTER STANDS ON ONE LEG.

甲擊手――

[5.20] A, strike to B’s hand.

用太陽劍平擊敵之手指。

Using a full active grip [tiger’s mouth facing to the right], strike across [leftward] to B’s fingers [while your left foot steps behind your right foot and you make an empty stance].

[photo for movement 5.19 and the first part of movement 5.20, showing A on the left, B on the right]

甲乙各提劍保門,甲先提,乙隨之。

Both of you then make a lifting posture, A [B] lifting first, then B [A], then return to the guarding posture.

[photo for the second part of movement 5.20, showing A on the left, B on the right]

(上半完)。

(This completes the first part of Section Five.)

–

[SECTION FIVE – Part 2]

甲乙各作伏勢――

[5.21] Both of you, get into a crouching posture.

見前。

Same as before [movement 5.1].

乙上步刺胸――

[5.22] B, step forward and stab to A’s chest.

上右足,用中陰劍,直刺敵腹。甲上步平擊。

Step forward with your right foot as you use a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to do a vertical-blade stab to A’s belly [chest]. A at the same time steps forward and strikes across [leftward, to B’s wrist].

對提――

[5.23] Both of you, make a lifting posture.

見前各式中。

Same as before [second part of movement 5.20].

[photo for movement 5.23, showing A on the left, B on the right]

對劈――

[5.24] Both of you, chop at each other.

用中陰劍直劈,取敵之左方,與以前各式中取敵之右方者不同。

Using a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward], chop with the blade vertical, this time seeking the opponent on his left side, different from the previous times [movements 1.15 & 2.11], which sought him on his right side.

對刺腹――

[5.25] Both of you, stab toward your opponent’s belly.

中陰劍直刺。

Use a half passive grip [tiger’s mouth facing upward] to do a vertical-blade stab.

甲反格腕――

[5.26] A, do an overturned block to B’s wrist.

中陰劍從敵腕下方反格。

Using a half passive [half active] grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward], do an overturned block under B’s wrist.

乙反帶腕――

[5.27] B, do a reverse drag to A’s wrist.

開左足,向左斜方上,全體向左傾,右手從敵腕上以中陽劍往左一帶。

Step out your left foot diagonally to the forward left [left rear] and lean your body to the left as you use a half active grip [tiger’s mouth facing downward] to do a dragging cut to the left along the top of A’s wrist [using the inner edge].

[photo for movement 5.26 & 5.27, showing B on the left, A on the right (reverse view)]

[The 1931 book uses this photo to illustrate an action of vertical-blade stabbing with the wrist turned over, akin to the stabbing action in movement 2.4, meaning that the overturned block should perhaps also have an intention of reaching forward.]

甲反腕帶――

[5.28] A, turn over your wrist and drag.

與第三路末式乙之動作同。

Same as B’s final movement in Section Three [movement 3.13, meaning that you turn over your sword and do a dragging cut on top of B’s wrist].

各轉身劈――

[5.29] Both of you, turn your body and chop.

雙手捧劍,劍尖向下,轉身向右,上左足,復轉身退右足,當轉身退右足時,趁勢將劍舉起劈下。各保門。

Hold your sword with both hands, the tip angled downward, then turn your body to the right as you step forward with your left foot and then continue turning your body as you retreat your right foot. As you are turning, [bringing your left foot forward,] and retreating your right foot, take advantage of the momentum of these actions by raising your sword and chopping down. Then return to the guarding posture. [The 1931 book then mentions that this is followed by a “closing posture”, but does not explain how it is to be performed. The safest bet is probably the very generic action of grabbing the sword in your left hand and lowering it to your left side so the sword is standing behind your arm, your right hand lowering with it and then circling to your right, up, and back down in front of you with the hand still formed as a spearing finger, pushing down in front of your belly.]

(完)共計三十式不同者十二式。

(This completes the whole of Section Five, which has a total of thirty [twenty-nine] movements and is comprised of twelve different techniques.)

–

[POSTSCRIPT]

武當劍法五路共百一十劍,其中不同者有六十劍,李芳宸先生所傳也。武林黃文叔為先生入室弟子,余從文叔遊,因得而私淑焉。憶龍年寓杭垣湧金門時,距文叔之西湖新宅不數里,晨夕過從,每當酒酣耳熱,輒相與起舞,意氣豪甚。顧此年衰病侵尋,置不復習,強半遺忘,甚矣余之惰而荒也。今春遇文叔於滬上,彼方以劍法授潘子時雨,傅子養德,徐子梅岐,且假余庭固為演練之場,於是向之遺忘者歷歷然復印諸心目,濡筆記之備他日復習之用,且以記此一段因緣云。

民國二十八年歲次已卯三月一日 易範齋主人子慕跋

The five sections of the Wudang Sword set have a total of a hundred and ten [hundred and nine] movements, comprised of sixty distinct techniques. It was taught by Li Fangchen [Jinglin]. Huang Wenshu [Yuanxiu] was his indoor disciple. I learned it from Huang because I had no opportunity to learn it from Li. I remember that in the last year of the dragon [1928] I was living in Hangzhou, near Yongjin Gate, not many miles from Huang’s new house at West Lake. We spent time together constantly, always drinking wine, exuberant in each other’s company, our spirits unrestrained.

But during this last year, I was gradually weakened by illness and ceased practicing what I had learned. I have now forgotten more than half of the set, so rusty have I become in my lethargy. This spring, I received Huang in Shanghai so that other students he had taught the sword set to – Pan Shiyu, Fu Yangde, and Xu Meiqi – could borrow the use of my courtyard as a practice space. Because of this, all I had forgotten was clearly restored, imprinted on my mind. I then made these notes of it so that I can have something to refer to when I start practicing again, and I here make a record of the event with these brief words.

- written with esteem by your student, Yi Fanzhai, 16th year of the cycle, 3rd month, 1st day [April 20, 1939]

–

–

–

In 1938, Henan province was the centre of an ongoing effort by the Nationalist Government (Guomingdang, KMT) to stop the advance of the Japanese troops. Many local young men were conscripted into the army. The combination of natural and human factors ravaged Henan proivince. In 1941, locusts plagued Wen county and the Guomingdang (KMT) had taken controls over the area. Henan province was divided into the eastern half (under Japanese occupation) and the western half which was supposed to be under the Nationalist Government (based in Chongqing after fleeing Nanjing).

In 1938, Henan province was the centre of an ongoing effort by the Nationalist Government (Guomingdang, KMT) to stop the advance of the Japanese troops. Many local young men were conscripted into the army. The combination of natural and human factors ravaged Henan proivince. In 1941, locusts plagued Wen county and the Guomingdang (KMT) had taken controls over the area. Henan province was divided into the eastern half (under Japanese occupation) and the western half which was supposed to be under the Nationalist Government (based in Chongqing after fleeing Nanjing). In 1958, Chen Zhaopei whom resided in Zhengzhou at the time visited Chenjiagou for Chinese New Year. It was his first time back in decades. Chen Zhaopei whilst advanced in years (65) felt that it was a shame that there were no longer any practitioners in Chenjiagou. He was saddened that there were no successors in the birthplace of Taijiquan and no serious practitioners left in Chenjiagou. It was a difficult decision because at the time both his wife (second wife) and son (whom had a good job and family in Zhengzhou) were against him returning to Chenjiagou. He also had to retire from his work (Flood Control Committee) earlier foresaking an increase in his pension. Chen Zhaopei however against all odds felt a sense of responsibility and returned to the Chenjiagou during his retirement years. Unfortunately this was not going to be an easy quest for there were still a number of CCP initatives that impacted the ability to propagate and teach Taijiquan during those years. The Great Leap forward was distracting and in 1966-1976, The Cultural revolution saw the repression of traditional teachings including martial arts. Facilities were closed down and practitioners were prosecuted. Chen Zhaopei was said to have been persecuted by the red guards and even attempted suicide during those years. His legs were injured for almost two years and had to use a stool/walking assistance during the time. Much of the training had to be conducted in secret and many elements (eg weapons) a challenge to practice in confined space so mostly only the laojia yi lu was taught. After Chen Zhaopei’s death, Chen Zhaokui (Chen Fa’ke’s youngest son) continued teaching at Chenjiagou. The local secretary of the CCP for Wen County, Zhang Weizhen also invited Feng Zhiqiang to teach. Feng Zhiqiang visited three times for short intensive teaching sessions.

In 1958, Chen Zhaopei whom resided in Zhengzhou at the time visited Chenjiagou for Chinese New Year. It was his first time back in decades. Chen Zhaopei whilst advanced in years (65) felt that it was a shame that there were no longer any practitioners in Chenjiagou. He was saddened that there were no successors in the birthplace of Taijiquan and no serious practitioners left in Chenjiagou. It was a difficult decision because at the time both his wife (second wife) and son (whom had a good job and family in Zhengzhou) were against him returning to Chenjiagou. He also had to retire from his work (Flood Control Committee) earlier foresaking an increase in his pension. Chen Zhaopei however against all odds felt a sense of responsibility and returned to the Chenjiagou during his retirement years. Unfortunately this was not going to be an easy quest for there were still a number of CCP initatives that impacted the ability to propagate and teach Taijiquan during those years. The Great Leap forward was distracting and in 1966-1976, The Cultural revolution saw the repression of traditional teachings including martial arts. Facilities were closed down and practitioners were prosecuted. Chen Zhaopei was said to have been persecuted by the red guards and even attempted suicide during those years. His legs were injured for almost two years and had to use a stool/walking assistance during the time. Much of the training had to be conducted in secret and many elements (eg weapons) a challenge to practice in confined space so mostly only the laojia yi lu was taught. After Chen Zhaopei’s death, Chen Zhaokui (Chen Fa’ke’s youngest son) continued teaching at Chenjiagou. The local secretary of the CCP for Wen County, Zhang Weizhen also invited Feng Zhiqiang to teach. Feng Zhiqiang visited three times for short intensive teaching sessions.