–

燕青單刀

YAN QING’S SINGLE SABER

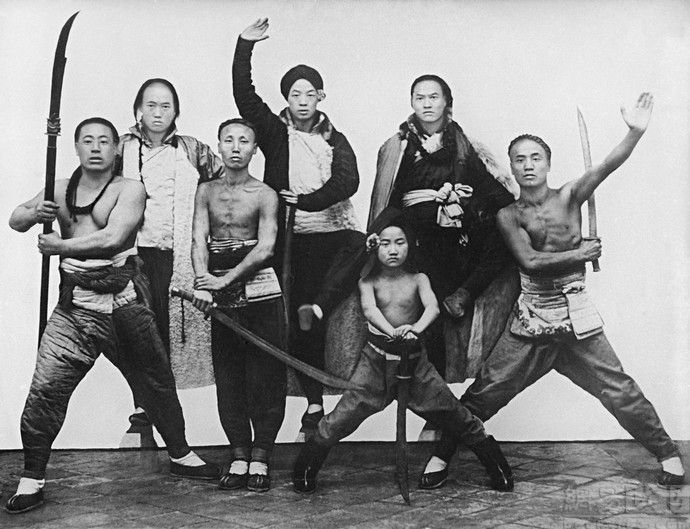

順德黃漢勛編述

by Huang Hanxun [Wong Honfan] of Shunde

山東蓬萊羅光玉老師授

as taught by Luo Guangyu of Penglai, Shandong

攝影者:譚以禮

postures photographed by Tan Yili

校對者:黃子英

text proofread by Huang Ziying

[published 33rd year of the cycle, 6th month, 1st day (Jul 8, 1956)]

[translation by Paul Brennan, Dec, 2018]

–

㷼青單刀

Yan Qing’s Single Saber

黃漢勋自署

– calligraphy by Huang Hanxun

–

燕青单刀形勢圖

Map for the postures in the set:

图例:凢由東至西。或由西返東之直線形。皆以同一線為凖。其分線繪图者。不外為利便絵圖耳。

The postures will travel from east to west, then come back from west to east [and then once more from east to west and west to east], both ways in a straight line. These lines are drawn simply for convenience.

S

南

E 東 + 西 W

北

N

–

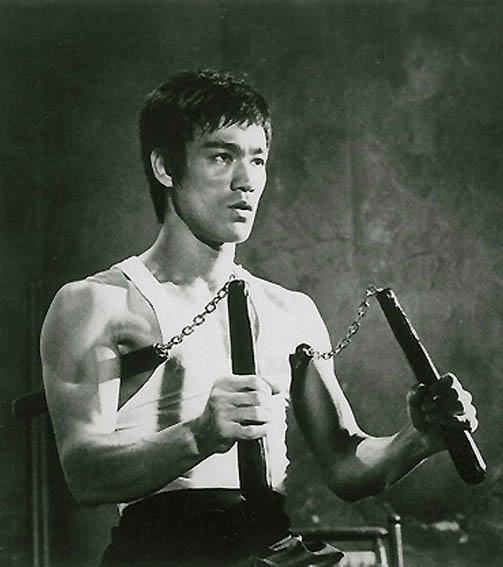

試刀小言

A FEW WORDS ON EXAMINING THE SABER

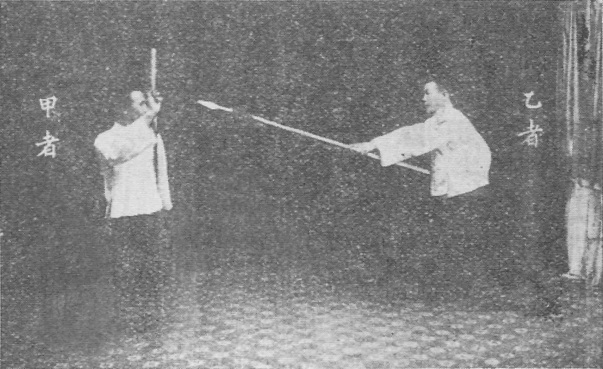

古俠士與武林先哲嘗以得寶刀寶劍為榮,其得寶也必先看之,試之,以攷其實,精武前輩,盍煒昌先生嘗贈余以試劍圖乙幀,盧君致力武道四十年其神彩至為活現,余以此刀祗得五十五圖,因補撕此圖以凑合篇幅耳,若云以先哲前賢自視,能勿愧煞乎!抑亦能毋有東施效顰之嫌歟。

Ancient warriors and wise men within the martial arts community considered it an honor to receive a “precious saber” or a “precious sword”. But to test whether it was really a precious blade, they first had to examine it [by drawing it from its scabbard, as in the photo]. Jingwu elder Lu Weichang once gave me a photo of himself examining a sword. He devoted himself to martial ways for forty years and his passion for it was visible. Although this saber set in this book contains only fifty-five postures, it may seem that the addition of this one photo makes the book too long. If it makes you think that I consider myself to be on a par with previous masters like Lu, shame on you. Do not imagine for an instant that I am trying to make some pathetic attempt to imitate that great man.

–

自序

AUTHOR’S PREFACE

單刀一械為步戰中慣用武器之一,其法乃脫胎於大刀而大盛於宋明及亡淸,宋末水滸傳中之浪子燕靑即以單刀法見稱於世矣,其後王五亦以單刀著譽武林,「人或以大刀王五稱之。」余則以為王所用刀畧大而已,並非為大砍刀之大刀也,燕靑單刀僅傳五十五刀法,中有重式者,除外則半耳!單刀有十法,即劈,軋,抅,掛,削,拍,挑,撩,搜,撈,也。漢雖曾一個時期致力於此,祗惜二十年來,就食四方是以致技術生疏退板,且以個人精神魄力去應需求不同之習技者,是難得專心致意於某一技之機會,茲僅拾遺法於萬一用以列諸於冊,雖未能揚前人之美妙,但尤勝乎昧昧於心而藏諸黃土之為計也,但願人人以發揚國粹自任,使具有民族性之技術千古不替,是所厚幸焉。黃漢勛於丙申端午東方國術部

The single saber is a weapon that has been commonly used by infantry. Its techniques emerge from the large saber art and it flourished through the dynasties of Song, Ming, and right up until the end of the Qing. In the late Song Dynasty novel The Water Margin, the character of “The Wanderer” Yan Qing was well-known for his single saber skills. Later on [late 19th century], Wang Wu [Wang Zhengyi] also become famous in martial arts circles for his use of the single saber, and was sometimes known as “Large Saber Wang Wu”. I use a slightly larger saber than Wang did, and so it is not the “large cleaving saber” type of large saber. Yan Qing’s Single Saber is a set that contains only fifty-five postures, and half of them are repeats. The single saber art has ten techniques: chopping, rolling, hooking, hanging, slicing, patting, carrying, raising, searching, and scooping.

Although I at one time devoted myself to this set, that was twenty years ago, and I have since had my attention pulled in so many directions that my saber skill has rusted. Because the task I have dedicated myself to requires the training of many different abilities, it is difficult to get the chance to focus all of my attention on a single skill. This set that I have picked to be in this series of books is just one tiny sample from all that I have inherited. Although I cannot do justice to the brilliance of previous generations, I at least seek to overcome ignorance and reveal what might otherwise become buried away. I only wish for everyone to take it upon themselves to carry on our national culture and keep our nation’s arts from ever being replaced. This is my sincere hope.

- written by Huang Hanxun at the Far East Martial Arts Headquarters, 33rd year of the cycle, Dragon Boat Festival [which takes place on the 5th day of the 5th lunar month, hence June 13, 1956]

–

第一式 出步中平式

Posture 1: IN READINESS TO STEP OUT, STANDING STABLY

說明:

Explanation:

假定此刀擇定東方作起點者應背南,面北,右東,左西而立,注視西方,左手捧刀,刀沿臂緊貼,刀以不逾頭而與耳齊為合度右手掌貼身,垂下,如「定式圖」

Stand in the eastern part of the practice space to begin this set, with the south behind you, the north in front of you, the east to your right, the west to your left. Your gaze is to the west. Your left hand is holding the saber, the [back of the] saber touching along [the top of] the arm. The saber should not extend past your head and should instead be at ear level. Your right palm is hanging down near your body [thigh]. See photo 1:

功用:

Application:

刀勢尚未展開,故無功用可言。

In this posture, you have not yet reached out with the saber, and thus there is no application to speak of.

第二式 抱刀上步式

Posture 2: HOLDING THE SABER, STEP FORWARD

說明:

Explanation:

沿上式,先出右脚,右掌與刀向前直出,目向前視,如「過後式」甲,

Continuing from the previous posture, first your right foot goes out as your right palm and the saber go straight out forward. Your gaze is forward. See photo 2a:

再進左脚以成左跨虎步,右掌化作刁手與刀齊往後收,逾後逾佳,目注西而視,如『定式圖』

Then your left foot advances to make a left sitting-tiger stance as your right hand becomes a hooking hand and withdraws behind you in unison with the saber. The farther they reach back, the better. Your gaze is toward the west. See photo 2b:

功用:

Application:

刀尚未交於右手,故仍為開式之勢,尚無實用可言。

As the saber has not yet been switched to your right hand, this is still an opening posture, and thus there is still not really any application to speak of.

第三式 斜步四平式

Posture 3: DIAGONAL STEP, FOUR-LEVEL POSTURE

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先拉起左脚,復進前右脚,以成立正之勢,右手復化為掌與刀同時向西方舉出,如「過渡式甲圖」

Continuing from the previous posture, first your left foot lifts, then your right foot advances to stand next to it, making a posture of standing at attention, as your right hand changes back to a palm and goes out to the west together with the saber. See photo 3a:

再退右脚拉左脚以成向正西方之跨虎步,右掌自左腋下出而向上,刀往後斜拖,如『定式圖』。

Then your right foot retreats and your left foot pulls back to make a sitting-tiger stance facing toward the west as your right palm goes out upward from below your left armpit, the saber pulling back until it is diagonal behind you. See photo 3b:

功用:

Application:

此式雖然於刀尚無致用之處,但相傳江湖上之鑣囊乃懸於腋下者,因此右手返至腋內者即取鑣之意,復向上揚者,亦即投擲之暗示也,今之用鑣者少,因是而祗是象徵而已。

In this posture, the saber still has no practical function, but according to tradition, wandering entertainers had a dart pocketed below the armpit, thus the right hand goes toward the armpit with a sense of taking out the dart and then raises upward to represent throwing this hidden weapon. Those who use such darts are very rare nowadays, and thus this is simply a symbolic gesture.

第四式 竄跳出身式

Posture 4: LEAPING UP AND SENDING OUT YOUR BODY

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,刀不動,右掌化拳自腰部與左脚向西前方齊出如「過渡式甲圖「。

Continuing from the previous posture, the saber does not change its position as your right palm becomes a fist and punches out from your waist, your left foot kicking out at the same time, both going out toward the west in unison. See photo 4a:

再跳起以右掌拍落右膝部,刀畧向前伸,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then hop up, using your right palm to slap down against your right knee area, the saber slightly reaching forward. See photo 4b:

落右脚以成扑腿之勢,右掌變拳收腰,刀則轉至胸前,如「過渡丙式圖」。

Your right leg comes down [and your left leg extends forward] to make a reaching-leg stance as your right palm becomes a fist and withdraws to your waist, the saber arcing until in front of your chest. See photo 4c:

再起過左腰後,右拳自腰部衝出,如『定式圖』。

Then rise up, the saber passing the left side of your waist and going behind you as your right fist thrusts out from your waist. See photo 4d:

功用:

Application:

此蹤跳出身者是與敵求接近之意也,我先以拳腿攻之,再用扑腿法剷之,彼欲跳起卸避,我則轉馬用捶直統之也。

This technique of leaping up and sending my body out is for dissuading an opponent who wants to approach me. I first use a technique of fist and foot attacking simultaneously, then use a reaching-leg stance to shovel underneath him. He will thus want to jump away to evade me, so I switch my stance and send a thrust punch straight at him.

第五式 扑腿推刀式

Posture 5: REACHING-LEG STANCE, PUSHING THE SABER

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,左右脚不變原來位置,祗再由左登山步往後轉為扑腿耳!刀自後繞過面前,右拳變掌隨刀而轉如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, your feet stay in their location and you simply shift back to the rear, going from a left mountain-climbing stance to a reaching-leg stance [the photo showing more of a right mountain-climbing], the saber going from behind you, passing in front of you, [and arcing to the right,] your right fist becoming a palm and arcing along with the saber. See photo 5a:

再由左手將刀交於右手,復轉馬為左登山步,右刀平推與左上掌齊出,如『定式圖』。

Then your left hand sends the saber into your right hand and you switch back to a left mountain-climbing stance as your right hand pushes out the saber, the blade horizontal, your left hand going out at the same time. See photo 5b:

功用:

Application:

我已將刀交於右手,即是凖備作戰之暗示也,彼即自我頂上殺來一棍或一槍,我乃用左掌朝上迎之,右刀向其中部推出,使彼不及收械迎禦也。

Once I have switched the saber into my right hand, this means I am ready for combat. An opponent uses a staff or spear to smash onto my headtop, so I send my left palm upward to block it while my right hand sends my saber pushing outward to his middle area, leaving him unable to withdraw his weapon in time to defend against it.

第六式 拉刀收步式

Posture 6: PULLING THE SABER, GATHERING STEP

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,原步不變,左掌向前,右刀自前經過面前拉向背部,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with your stance not changing, your left palm goes forward as your right hand pulls the saber across from in front of you to be behind you. See photo 6a:

再以右後脚跟前如跨虎步形狀,刀循背部沿左臂直落止於腕上,左掌化刁手往後抅去,如『定式圖』。

Then your right foot follows forward to almost make a sitting-tiger stance as the saber passes through behind you and lowers along your left arm until above the wrist, your left palm becoming a hooking hand and hooking away to the rear. See photo 6b:

功用:

Application:

彼擬用長械迫我,我先用左手刁去來械,復以右刀自上而下,以資掩護,亦可作劈擊來械之用也。

An opponent using a long weapon tries to attack me, so I first use my left hand to hook it aside, then send my saber downward from above as a means of shielding myself, or I can also use this action to chop away his weapon.

第七式 竄跳囘身式

Posture 7: SCURRYING AWAY WITH THE BODY TURNED

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先將右脚開往東方如登山步,刀與左刁手畧掠開,目注視西後方,如「過渡式圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your right foot steps out toward the east as though to make a mountain-climbing stance, the saber and your left hooking hand slightly sweeping aside. Your gaze is behind you toward the west. See photo 7a:

再原式不變疾跳過西後方,如『定式圖』。

Then while maintaining this position, suddenly hop back [twice] to the west [east]. See photos 7b and 7c:

功用:

Application:

不論已否扣得來械,我皆向後撤退,以便靜觀其變,俟機出擊是也。

Regardless of whether or not I have succeeded in drawing aside the opponent’s weapon, I retreat to watch for what he will do next and wait for the opportunity to attack.

第八式 拉刀藏刀式

Posture 8: PULLING THE SABER INTO A STORING POSITION

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,刀與手不變,先進左脚,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with the saber and your left hand not changing their position, first your left foot advances. See photo 8a:

再轉右東而反向西方提起右脚,左刁手仍抅後,刀則沿右膝部殺落,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then turn around to the right to go from facing toward the east to be facing toward the west as your right foot lifts, your left hand still hooking behind, and the saber smashes down beside your right knee. See photo 8b:

左手與步不變,刀循前下方繞過背部,右手直舉,如「過渡式丙圖」。

With your left hand and legs not changing their position, the saber follows through forward and downward and arcs behind your back, your right arm rising until vertical. See photo 8c:

乘提右脚之便蹤身一跳,以成左跨虎之勢,刀則轉過左肩斜向前落,落時左手須由胸前化掌穿出為合如『定式圖』。

Going along with the lifting of your right leg, your body hops into a left sitting-tiger stance as the saber arcs past your left shoulder and lowers diagonally in front of you, your left hand becoming a palm and shooting out forward from in front of your chest at the same moment that the saber lowers. See photo 8d:

功用:

Application:

此式合卸步,提腿,蹤跳,攔刀,撇刀,拉刀等為一式,若善於運用則合攻守於一矣。

This posture combines a withdrawing step, lifting leg, hop, and the saber actions of blocking, swinging, and pulling into a single technique. If you are good at applying it, then defense and offense will be combined into a single action.

第九式 出步劈刀式

Posture 9: STEP OUT, CHOPPING

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,出右脚以成右登山步,刀自後向前劈去,再轉歸左方,左手則貼腕助之,如『定式圖』。

Continuing from the previous posture, your right foot goes out to make a right mountain-climbing stance as the saber chops out forward from the rear and follows through by arcing across to the left, your left hand touching your [right] wrist to assist. See photo 9:

功用:

Application:

彼械直刺我中門,我即用橫刀殺消之。

The opponent’s weapon stabs to my middle area, so I send my saber across to smash it away.

第十式 跟步軋刀式

Posture 10: FOLLOWING STEP, ROLLING THE SABER

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,左右脚不變,祗向一標,以成騎馬式,刀與掌同時向前後一分,如『定式圖』。

Continuing from the previous posture, your feet maintain their position and you simply dart forward to make a horse-riding stance, the saber and palm spreading apart forward and back. See photo 10:

功用:

Application:

彼械為我刀殺去,或為彼漏去,我皆復跟步進馬順刀劈之,斯為刀法之正着,抑亦與上式有連貫之作用也。

The opponent’s weapon has been smashed aside by my saber, or he has retreated, so I follow him by advancing into a horse-riding stance with my saber chopping out. This is a direct saber action and follows on from the previous posture to form a continuous technique.

第十一式 抱頭攔刀式

Posture 11: WRAPPING AROUND THE HEAD, SLASHING

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先提左後脚,刀自前轉後斜掛左肩之上,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first lift your left foot as the saber arcs to the rear to hang diagonally over your left shoulder. See photo 11a:

再以站地之脚,循左方移動,轉後反以後刀作前,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then pivot to the left on your standing foot to bring the saber from the rear to the front. See photo 11b:

再落右脚以成左登山式,刀由背後繞過再橫轉於前,如『定式圖』。

Then your right [left] foot comes down to make a left mountain-climbing stance as the saber passes behind your back and arcs across in front of you. See photo 11c:

功用:

Application:

彼繞過我背後實施襲擊,我即以刀掩護隨之而轉動,經一迎後再用橫刀法砍殺之。

The opponent slips around behind me to make a surprise attack, so I use my saber to shield myself as I pivot around to face him and then slash across at him.

第十二式 拉刀收步式

Posture 12: PULLING THE SABER, GATHERING STEP

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,原步不變,左掌向前,右刀自前經過面前拉向背部,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with your stance not changing, your left palm goes forward as your right hand pulls the saber across from in front of you to be behind you. See photo 12a:

再以右後脚跟前如跨虎步形狀,刀循背部沿左臂直落止於腕上,左掌化刁手往後抅去,如『定式圖』。

Then your right foot follows forward to almost make a sitting-tiger stance as the saber passes through behind you and lowers along your left arm until above the wrist, your left palm becoming a hooking hand and hooking away to the rear. See photo 12b:

功用:

Application:

彼擬用長械迫我,我先用左手刁去來械,復以右刀自上而下,以資掩護,亦可作劈擊來械之用也。

An opponent using a long weapon tries to attack me, so I first use my left hand to hook it aside, then send my saber downward from above as a means of shielding myself, or I can also use this action to chop away his weapon.

第十三式 竄跳囘身式

Posture 13: SCURRYING AWAY WITH THE BODY TURNED

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先將右脚開往東方如登山步,刀與左刁手畧掠開,目注視西後方,如「過渡式圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your right foot steps out toward the east as though to make a mountain-climbing stance, the saber and your left hooking hand slightly sweeping aside. Your gaze is behind you toward the west. See photo 13a:

再原式不變疾跳過西後方,如『定式圖』。

Then while maintaining this position, suddenly hop back [twice] to the west [east]. See photos 13b and 13c:

功用:

Application:

不論已否扣得來械,我皆向後撤退,以便靜觀其變,俟機出擊是也。

Regardless of whether or not I have succeeded in drawing aside the opponent’s weapon, I retreat to watch for what he will do next and wait for the opportunity to attack.

第十四式 拉刀藏刀式

Posture 14: PULLING THE SABER INTO A STORING POSITION

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,刀與手不變,先進左脚,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with the saber and your left hand not changing their position, first your left foot advances. See photo 14a:

再轉右東而反向西方提起右脚,左刁手仍抅後,刀則沿右膝部殺落,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then turn around to the right to go from facing toward the east to be facing toward the west as your right foot lifts, your left hand still hooking behind, and the saber smashes down beside your right knee. See photo 14b:

左手與步不變,刀循前下方繞過背部,右手直舉,如「過渡式丙圖」。

With your left hand and legs not changing their position, the saber follows through forward and downward and arcs behind your back, your right arm rising until vertical. See photo 14c:

乘提右脚之便蹤身一跳,以成左跨虎之勢,刀則轉過左肩斜向前落,落時左手須由胸前化掌穿出為合如『定式圖』。

Going along with the lifting of your right leg, your body hops into a left sitting-tiger stance as the saber arcs past your left shoulder and lowers diagonally in front of you, your left hand becoming a palm and shooting out forward from in front of your chest at the same moment that the saber lowers. See photo 14d:

功用:

Application:

此式合卸步,提腿,蹤跳,攔刀,撇刀,拉刀等為一式,若善於運用則合攻守於一矣。

This posture combines a withdrawing step, lifting leg, hop, and the saber actions of blocking, swinging, and pulling into a single technique. If you are good at applying it, then defense and offense will be combined into a single action.

第十五式 拉刀坐盤式

Posture 15: PULLING THE SABER, SITTING TWISTED STANCE

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,出右脚以成右登山式,刀自後向前劈,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, your right foot steps out to make a right mountain-climbing stance as the saber chops forward from behind. See photo 15a:

再原步不變將刀拉過右後方,左掌仍貼右腕,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then with your stance not changing, pull the saber through to the right rear, your left palm staying at your right wrist. See photo 15b:

再蹤身一跳,以成坐盤之勢,刀自右肩過左肩,沿左臂直落,左手化成刁手,以襯托刀背,如『定式圖』。

Then your body hops into a sitting twisted stance [i.e. your left foot going forward, then your right foot doing a stealth step behind it] as the saber goes past your right shoulder to your left shoulder and lowers along your left arm, your left hand becoming a hooking hand, the arm propping up the back of the saber. See photo 15c:

功用:

Application:

我旣已劈消來械,再進而坐盤以刀攔砍之。

Having chopped away an incoming weapon, I then advance into a sitting twisted stance while slashing with my saber.

第十六式 拉刀藏刀式

Posture 16: PULLING THE SABER INTO A STORING POSITION

說明:

Explanation:

循坐盤步向右轉,刀掠起至肩齊為止,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continue from the sitting twisted stance by turning around to the right as the saber sweeps across and rises to shoulder level. See photo 16a:

再全身躍起變成向南之左跨虎步,刀自右肩轉過左肩,沿左臂之上削出,左掌則自刀背穿出,如『定式圖』。

Then your body hops into a left sitting-tiger stance facing toward the south as the saber arcs past your right shoulder to your left shoulder and then slices out over your left arm, your left palm shooting out from the back of the saber. See photo 16b:

功用:

Application:

與第八,第十四等式同,祗差方向耳。

Same as in Postures 8 and 14, except that the orientation is different.

第十七式 抱頭攔刀式

Posture 17: WRAPPING AROUND THE HEAD, SLASHING

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先提左脚,刀向額上舉起,左掌貼腕,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first lift your left foot as you lift the saber toward your forehead, your left palm touching your [right] wrist. See photo 17a:

再落下左脚,以成左登山式,刀由背後轉而過於面前,橫殺而出,如『定式圖』。

Then your left foot comes down to make a left mountain-climbing stance as the saber arcs around behind your back and goes out in front of you, smashing across. See photo 17b:

功用:

Application:

與第十一式同,祗方向之異耳。

Same as in Posture 11, except that the orientation is different.

第十八式 囘身掠翅式

Posture 18: TURN AROUND, SPREADING WINGS

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,步由左登山向後轉為右登山式,刀與手皆由後轉前向左右掠開,手與刀俱平正為合,如『定式圖』

Continuing from the previous posture, pivot to the rear to switch from a left mountain-climbing stance to a right mountain-climbing stance while the saber and your left hand arc forward from behind and spread open to the sides. The hand and saber should be spread equally. See photo 18:

功用:

Application:

彼械自我後進擊,我為求迅予抵禦計,乃原步化後作前,同時以手與刀左右分之。

An opponent’s weapon attacks me from behind, so I seek to quickly defend against it by staying where I am and changing the rear into the front while spreading to the sides with my left hand and my saber.

第十九式 順步軋刀式

Posture 19: SLIDING STEP, ROLLING THE SABER

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先拉起右脚如跨虎步之狀,刀往後拖去,如「過渡式用圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first pull back your right foot, almost making a sitting-tiger stance as the saber pulls to the rear. See photo 19a:

復借拉步而往前標去,以成右登山步,刀自後反刀鋒向上軋出,如『定式圖』。

Then make use of the reversal of momentum of the foot pulling back to dart forward into a right mountain-climbing stance as the saber goes out from the rear, rolling over so the edge is turned upward. See photo 19b:

功用:

Application:

我先拖歸後者是卸其勢,再軋出則是順而反撩之法也。

I first pull to the rear with a withdrawing action, then send out the saber rolling over into a raising action.

第二十式 囘身劈刀式

Posture 20: TURNING THE BODY, CHOP

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,原步原刀不變,祗左手以刁手法往後刁去,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, your stance and the position of the saber do not change as your left hand becomes a hooking hand and hooks away to the rear. See photo 20a:

再原步轉歸後方以成左登山式,刀自後反身由上劈落,左手化掌力托之,如『定式圖』。

Then your feet turn to the rear while staying in their location, making a left mountain-climbing stance, as the saber goes from behind you and chops down from above, your left hand changing to a palm and forcefully propping it up [i.e. slapping against your right wrist]. See photo 20b:

功用:

Application:

彼自我後劈來一械,我先以刁手斜刁之,再囘身用劈殺法迎頭砍之。

An opponent’s weapon chops at me from behind, so I first use a hooking hand to diagonally hook it aside, then turn my body and chop to his head.

第二十一式 撩刀提劈式

Posture 21: RAISING CUT, LIFTING INTO A CHOP

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,原步仍未變,祗身畧轉過右後方,刀亦隨身轉上為下,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, your stance does not change, but your body slightly turns to the right rear, the saber going along with your body by arcing downward from above. See photo 21a:

再踏右脚,進左脚以成騎馬式,刀隨步轉而歸後,左掌以揷掌法撑出且注以目,如『定式圖』。

Then your right foot stomps and your left foot advances to make a horse-riding stance as the saber arcs to the rear, your left hand going out as a charging palm, your gaze following it. See photo 21b:

功用:

Application:

彼械擬向我膝部點來,我先用下撩之法,再轉馬迎胸以掌揷進焉。

An opponent [from behind] tries to use his weapon to do a tapping attack to my [right] knee, so I first send a raising action against it from below, then switch to a horse-riding stance and attack with a charging palm to his chest.

第二十二式 上步軋刀式

Posture 22: STEP FORWARD, ROLLING THE SABER

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,進右脚以成右登山式,刀自後下方直向前上撩出,如『定式圖』。

Continuing from the previous posture, your right foot advances to make a right mountain-climbing stance as the saber goes from the rear, downward, forward, and upward to go out with a raising action. See photo 22:

功用:

Application:

與第十九式同。

Same as in Posture 19.

第二十三式 掛刀蓋刀式

Posture 23: HANGING & COVERING

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先提右前脚,刀往後收,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your right foot lifts as the saber withdraws. See photo 23a:

再乘提步之便全身躍起,落下時乃成左跨虎步,刀轉成橫壓而下,左手按於刀背之上,如『定式圖』。

Then go along with the momentum of the leg lifting by hopping [forward] and coming down into a left sitting-tiger stance as the saber arcs across and presses down, your left hand pushing on the back of the saber. See photo 23b:

功用:

Application:

彼械自我下刺來,我先以刀背掛去之,再乘躍進時更以刀橫壓之。

The opponent’s weapon stabs to my lower area, so I first use the back of my saber to hang it aside, then hop forward and press down with my saber placed sideways.

第二十四式 踏步攔腰式

Posture 24: STOMP, SLASH TO THE WAIST

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先放下前脚,手與刀同時向頭上舉起,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first put your front foot down as your left hand and the saber lift above your head. See photo 24a:

再踏後脚,進前脚以成左登山式,刀自左方轉過背後,再向前橫殺去,如『定式圖』。

Then your rear foot stomps and your front foot advances to make a left mountain-climbing stance as the saber arcs from the left, passing behind your back, and smashes across in front of you. See photo 24b:

功用:

Application:

與十一式,十七式等同。

Same as in Postures 11 and 17.

第二十五式 拉刀收步式

Posture 25: PULLING THE SABER, GATHERING STEP

說明:

Explanation:

循上左,原步不變,左掌向前,右刀自前經過面前拉向背部,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with your stance not changing, your left palm goes forward as your right hand pulls the saber across from in front of you to be behind you. See photo 25a:

再以右後脚跟前如跨虎步形狀,刀循背部沿左臂直落止於腕上,左掌化刁手往後抅去,如「定式圖」。

Then your right foot follows forward to almost make a sitting-tiger stance as the saber passes through behind you and lowers along your left arm until above the wrist, your left palm becoming a hooking hand and hooking away to the rear. See photo 25b:

功用:

Application:

彼擬用長械迫我,我先用左手刁去來械,復以右刀自上而下,以資掩護,亦可作劈擊來械之用也。

An opponent using a long weapon tries to attack me, so I first use my left hand to hook it aside, then send my saber downward from above as a means of shielding myself, or I can also use this action to chop away his weapon.

第二十六式 竄跳囘身式

Posture 26: SCURRYING AWAY WITH THE BODY TURNED

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先將右脚開往東方如登山步,刀與左刁手畧掠開,目注視西後方,如「過渡式圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your right foot steps out toward the east as though to make a mountain-climbing stance, the saber and your left hooking hand slightly sweeping aside. Your gaze is behind you toward the west. See photo 26a:

再原式不變疾跳過西後方,如「定式圖」。

Then while maintaining this position, suddenly hop back [twice] to the west [east]. See photos 26b and 26c:

功用:

Application:

不論已否扣得來械,我皆向後撤退,以便靜觀其變,俟機出擊是也。

Regardless of whether or not I have succeeded in drawing aside the opponent’s weapon, I retreat to watch for what he will do next and wait for the opportunity to attack.

第二十七式 拉刀坐盤式

Posture 27: PULLING THE SABER, SITTING TWISTED STANCE

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,原步不變,刀自左方拉過右方,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with your stance not changing, pull the saber across from left to right. See photo 27a:

再全身躍起以成坐盤步,刀自右肩轉過左肩,再沿左臂直落,左刁手托於刀背之中段,如『定式圖』。

Then your body hops into a sitting twisted stance [i.e. your left foot going forward, then your right foot doing a stealth step behind it] as the saber arcs past your right shoulder to your left shoulder and lowers along your left arm, your left hand becoming a hooking hand, the arm propping up the middle section of the back of the saber. See photo 27b:

功用:

Application:

當我正自前方撤退之時,迎面忽來另一敵人,於是我乃以拉刀坐盤法以抑制之。

While retreating away from one opponent, I am suddenly faced with another, so I use this technique of pulling my saber while going into a sitting twisted stance in order to control him.

第二十八式 獻刀藏刀式

Posture 28: SHOWING AND THEN HIDING THE SABER

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,原步不變,祗高起偸步式,手與刀俱掠起,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with your stance not changing, rise up high in your stealth-step position as your left hand and the saber spread apart and rise up. See photo 28a:

再右後脚抽出,繞過面前,刀則攔於左上方,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then your right foot draws out from behind and arcs around in front of you as the saber blocks to the upper left. See photo 28b:

再乘提右脚之勢跳往左方,再成為狀類左登山式之右吞塌式,刀自背繞過面前,復收於左腰腋之間,目向後注視,如『定式圖』。

Then take advantage of the momentum of your right foot lifting by hopping to the left to make a right absorb & sink stance, similar to a left mountain-climbing stance [except that you are looking to the rear], as the saber arcs around past your back and in front of you to withdraw to the area between your left armpit and your waist. Your gaze is behind you. See photo 28c:

功用:

Application:

彼械擬自我斜方攻來,我即轉身易步用提與攔劈之方式抵禦之。

An opponent’s weapon tries to attack me from an angle, so I turn to face him while shifting my stance, using a technique of lifting and slashing to defend against it.

第二十九式 拉刀藏刀式

Posture 29: PULLING THE SABER INTO A STORING POSITION

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,刀與手不變,先進左脚,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with the saber and your left hand not changing their position, first your left foot advances. See photo 29a:

再轉右東而反向西方提起右脚,左刁手仍抅後,刀則沿右膝部殺落,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then turn around to the right to go from facing toward the east to be facing toward the west as your right foot lifts, your left hand still hooking behind, and the saber smashes down beside your right knee. See photo 29b:

左手與步不讓,刀循前下方繞過背部,右手直舉,如「過渡式丙圖」。

With your left hand and legs not changing their position, the saber follows through forward and downward and arcs behind your back, your right arm rising until vertical. See photo 29c:

乘提右脚之便蹤身一跳,以成左跨虎之勢,刀則轉過左左肩斜向前落,落時左手須由胸前化掌穿出為合如「定式圖」

Going along with the lifting of your right leg, your body hops into a left sitting-tiger stance as the saber arcs past your left shoulder and lowers diagonally in front of you, your left hand becoming a palm and shooting out forward from in front of your chest at the same moment that the saber lowers. See photo 29d:

功用:

Application:

此式合卸步,提腿,蹤跳,攔刀,撇刀,拉刀等為一式,若善於運用則合攻守於一矣。

This posture combines a withdrawing step, lifting leg, hop, and the saber actions of blocking, swinging, and pulling into a single technique. If you are good at applying it, then defense and offense will be combined into a single action.

第三十式 劈刀軋刀式

Posture 30: CHOPPING & ROLLING

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先出右脚以成右登山步,刀自後劈出,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, your right foot goes out to make a right mountain-climbing stance as the saber chops out from the rear. See photo 30a:

再轉步為騎馬式,刀自面前斜方向直綫劈出,如『定式圖』。

Then switch to a horse-riding stance as the saber moves diagonally from in front of you to chop out straight ahead. See photo 30b:

功用:

Application:

介乎第九第十式之間,抑亦為聯合之法也。

Same as in Postures 9 and 10, combined into a single technique.

第三十一式 掛刀掛劍式

Posture 31: HANGING THE SABER TO HANG ASIDE A SWORD

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先提右脚,刀往左後方平收,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your right foot lifts as the saber withdraws across to the left rear. See photo 31a:

步仍不變,刀由後轉前,反刀鋒為向上,如「過渡式乙圖」。

With your stance not changing, the saber arcs forward from the rear, turning over so the edge is facing upward. See photo 31b:

然後向前跳去,以成坐盤之勢,刀由上橫殺而落,左掌按於刀背之上,如『定式』。

Then you hop out forward to make a sitting twisted stance as the saber smashes down from above with the blade going across, your left hand pushing on the back of the saber. See photo 31c:

功用:

Application:

我提步收刀者,是將來刀掛開,再反出者亦為掛刀之一法,再進馬坐盤橫壓刀者,則是蓋去來劍之法。

When I lift a leg and withdraw my saber, this is a means of hanging aside an incoming weapon. When I then turn the saber over, this is also a method of hanging. When I then advance into sitting twisted while pressing my saber across, this is a method of covering an incoming sword.

第三十二式 囘身劈刀式

Posture 32: TURNING THE BODY, CHOP

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,退右脚以成騎馬式,刀隨而平殺過後方,如「定式圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, your right foot retreats to make a horse-riding stance as the saber smashes across to the rear. See photo 32:

功用:

Application:

與廿一式圖同。

Same as in Posture 21.

第三十三式 上步軋刀式

Posture 33: STEP FORWARD, ROLLING THE SABER

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,進右脚以成右登山式,刀自後下方直向前上撩出,如「定式圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, your right foot advances to make a right mountain-climbing stance as the saber goes from the rear, downward, forward, and upward to go out with a raising action. See photo 33:

功用:

Application:

與二十二式同。

Same as in Posture 22.

第三十四式 踏步劈刀式

Posture 34: STOMPING STEP, CHOPPING

說明:

Explanation:

循上式原步不動,刀向後斜收,左手向前刁去,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with your stance not changing, the saber withdraws diagonally to the rear while your left hand goes forward, hooking away. See photo 34a:

再踏右脚,進左脚以成左登山式,左刁手拉歸後,而刀則向前直劈去,如「定式圖」。

Then your right foot stomps and your left foot advances to make a left mountain-climbing stance as your left hooking hand pulls back behind you and the saber chops out forward with the blade standing straight up. See photo 34b:

功用:

Application:

彼欲以械擊我頭部,我先以左手刁去之,再乘踏步進馬,以直劈刀兜頭劈之。

The opponent tries to use his weapon to strike to my head, so I first use my left hand to hook it away, then stomp and advance while using my saber to chop to his face.

第三十伍式 扑刀推刀式

Posture 35: REACHING-LEG STANCE, PUSHING THE SABER

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,左右脚不變原來位置,祗由登山式往後扑成扑腿法耳!刀亦隨步而下,左掌刀托於右腕之內,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, your feet stay in their location and you simply shift back to the rear, going from a mountain-climbing stance to a reaching-leg stance, the saber going along with this stance change by coming down, your left hand propping up at the inside of your right wrist. See photo 35a:

再提起右脚,左掌移開以托刀背,刀斜舉向外,如『定式圖』。

Then your right foot lifts and your left hand shifts away to prop up the back of the saber as the saber goes outward, raising diagonally. See photo 35b:

功用:

Application:

彼械迎頭劈落,我先扑腿以卸其勢,復跟刀推出逼之。

The opponent’s weapon chops down toward my head, so I first go into a reaching-leg stance in order to withdraw away from it, then I follow this by pushing out with the saber to crowd him.

第三十六式 提步劈刀式

Posture 36: CHOPPING WITH A LEG LIFTED

〔說明:〕

[Explanation:]

循上式,以小跳換步法,使右脚着地而起左脚,刀自前往後直劈,左掌橫遮於頭上,如『定式圖』。

Continuing from the previous posture, do a small hop to switch feet, bringing your right foot down and lifting your left foot, as the saber chops from the front to the rear, your left palm blocking across above your head. See photo 36:

功用:

Application:

我逼彼走過後方或另一人自後攻來,我不俟其逼近即先以刀兜頭劈之。

I crowd the opponent as he passes around behind me, or another opponent attacks from behind, so without waiting for him to get close, I pre-empt him by chopping to his head.

第三十七式 迎門刺劍式

Posture 37: STABBING STRAIGHT AHEAD LIKE A SWORD

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先左脚落地,刀斜掛於前,如「過渡式甲圖」

Continuing from the previous posture, first your left foot comes down and the saber hangs diagonally in front of you. See photo 37a:

再原刀不動,右脚進前,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then with the saber maintaining its position, your right foot advances. See photo 37b:

左脚自後進前以成坐盤步,刀則緊收於胸腹之間,如「過渡式丙圖」。

Your left foot advances behind you [i.e. does a stealth step] to make a sitting twisted stance as the saber withdraws until between your chest and belly. See photo 37c:

再原步不變,刀自胸前直流而出,掌則橫掠於上,如『定式圖』。

With your stance not changing, the saber flows straight out from in front of your chest, as your left palm spreads away upward to the side. See photo 37d [same position as in photo 4b of Sundial Sword, except with the edge turned upward]:

功用:

Application:

分圖多,是因易於學習耳!其用時合數動作於一。實集,挑,迎,封,閉,刺於其中矣。

This technique is divided into so many photos just to make it easier for you to follow. It contains several aspects in application – such as gathering, carrying, blocking, sealing, and stabbing – but is really just a single technique.

第三十八式 跟馬三刀式

Posture 38: FOLLOWING STEPS WITH THREE SABER ACTIONS [the third occurring in the following posture]

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先提起左脚,繼而伸直右手以舉直刀,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first lift your left foot as your right hand raises the saber. See photo 38a:

再原步不變,刀由右繞過背部,再經胸前而復返於下,左掌則抺刀背而出,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then with your stance not changing, the saber arcs from the right, going around your back, passes in front of your chest, and then goes back downward as your left palm goes out wiping along the back of the saber. See photo 38b:

再落左脚換提右脚,復將刀拉起,如「過渡式丙圖」

Then your left foot comes down and you switch to lifting your right foot as you again pull the saber up. See photo 38c:

再原步不動,刀再循背部拉前,後歸於後下方,左掌穿出至直,如『定式圖』。

Then with your stance not changing, the saber again goes around your back, is pulled in front of you, and returns downward to the rear as your left palm shoots out. See photo 38d:

功用:

Application:

提步攔刀實對中下路之攻勢為有效之遏止方法,左右相轉者乃使知左右合一之方式而已。

Lifting a leg and slashing with the saber is a very effective method of dealing with an attack to the middle or lower area. Switching my legs allows me to feel more confident that I am protecting myself on both sides.

第三十九式 扑腿扑刀式

Posture 39: REACHING-LEG STANCE, POUNCING SABER

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先原步不動,再次將刀舉起,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with your stance not changing, again lift up the saber. See photo 39a:

然後以小跳方式向前落下以成扑腿勢,刀亦隨步繞過背部再轉於前落下,左掌直出,如『定式圖』。

Then do a little hop forward and dropping down to make a reaching-leg stance as the saber arcs past your back, forward, and downward, your left palm going straight out. See photo 39b:

功用:

Application:

彼以下三路搶進,我即落馬用刀封閉之。

The opponent uses his spear to attack my lower area for the third time, so I drop my stance and use my saber to seal off his weapon.

第四十式 囘身削櫈式

Posture 40: TURN AROUND, SLICE THROUGH A STOOL

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先將左脚拉起以成類於登山勢,刀乃隨之起至頭上,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your left foot pulls back and you rise to almost make a mountain-climbing stance, the saber going along with this action by rising above your head. See photo 40a:

再起右後脚,使全身向左轉過後方,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then your right foot lifts and you pivot your whole body to the left until facing to the rear. See photo 40b:

落右脚以成騎馬式,刀繞過背後復轉平殺而出,左掌倚右肩之上,如『定式圖』。

Your right foot comes down to make a horse-riding stance as the saber arcs around behind you and smashes across [to the left], your left palm going over your right shoulder. See photo 40c:

功用:

Application:

此削櫈法乃專砍殺步馬為主旨對方欲自我後擊入,我乃採此以砍其足也。

The main purpose of this action of “slicing through a stool” is to destroy an opponent’s stance. An opponent is about to attack me from behind, so I make use of this technique to slash at his leg.

第四十一式 扑腿扑刀式

Posture 41: REACHING-LEG STANCE, POUNCING SABER

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先原步不動,再次將刀舉起,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with your stance not changing, again lift up the saber. See photo 41a:

然後以小跳方式向前落下以成扑腿勢,刀亦隨步繞過背都再轉於前落下,左掌直出,如『定式圖』。

Then do a little hop forward and dropping down to make a reaching-leg stance as the saber arcs past your back, forward, and downward, your left palm going straight out. See photo 41b:

功用:

Application:

彼以下三路搶進,我即落馬用刀封閉之。

The opponent again uses his spear to attack my lower area, so I again drop my stance and use my saber to seal off his weapon.

第四十二式 上步攔腰式

Posture 42: STEP FORWARD, SLASH TO THE WAIST

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先起左脚以成如登山之勢,將刀橫架而起,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your left leg rises to almost make a mountain-climbing stance as you send the saber upward and blocking across. See photo 42a:

再進右脚轉身乃成成左登山式,刀自背後橫過而前,如『定式圖」。

Then your right foot advances and your body turns around to make a left mountain-climbing stance as the saber passes behind your back and goes across in front of you. See photo 42b:

功用:

Application:

與十七、二十四等同。

Same as in Postures 17 and 24.

第四十三式 拉刀收步式

Posture 43: PULLING THE SABER, GATHERING STEP

說明:

Explanation:

循上左,原步不變,左掌向前,右刀目前經過面前拉向背部,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with your stance not changing, your left palm goes forward as your right hand pulls the saber across from in front of you to be behind you. See photo 43a:

再以右後脚跟前如跨虎步形狀,刀循背部沿左臂直落止於腕上,左掌化刁手往後抅去,如「定式圖」。

Then your right foot follows forward to almost make a sitting-tiger stance as the saber passes through behind you and lowers along your left arm until above the wrist, your left palm becoming a hooking hand and hooking away to the rear. See photo 43b:

功用:

Application:

彼擬用長械迫我,我先用左手刁去來械,復以右刀自上而下,以資掩護,亦可作劈擊來械之用也。

An opponent using a long weapon tries to attack me, so I first use my left hand to hook it aside, then send my saber downward from above as a means of shielding myself, or I can also use this action to chop away his weapon.

第四十四式 竄跳囘身式

Posture 44: SCURRYING AWAY WITH THE BODY TURNED

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先將右脚開往東方如登山步,刀與左刁手畧掠開,目注視西後方,如「過渡式圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your right foot steps out toward the east as though to make a mountain-climbing stance, the saber and your left hooking hand slightly sweeping aside. Your gaze is behind you toward the west. See photo 44a:

再原式不變疾跳過西後方,如「定式圖」。

Then while maintaining this position, suddenly hop back [twice] to the west [east]. See photos 44b and 44c:

功用:

Application:

不論已否扣得來械,我皆向後撤退,以便靜觀其變,俟機出擊是也。

Regardless of whether or not I have succeeded in drawing aside the opponent’s weapon, I retreat to watch for what he will do next and wait for the opportunity to attack.

第四十五式 拉刀藏刀式

Posture 45: PULLING THE SABER INTO A STORING POSITION

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,刀與手不變,先進左脚,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with the saber and your left hand not changing their position, first your left foot advances. See photo 45a:

再轉右東而反向西方提起右脚,左刁手仍抅後,刀則沿右膝部殺落,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then turn around to the right to go from facing toward the east to be facing toward the west as your right foot lifts, your left hand still hooking behind, and the saber smashes down beside your right knee. See photo 45b:

左手與步不讓,刀循前下方繞過背部,右手直舉,如「過渡式丙圖」。

With your left hand and legs not changing their position, the saber follows through forward and downward and arcs behind your back, your right arm rising until vertical. See photo 45c:

乘提右脚之便蹤身一跳,以成左跨虎之勢,刀則轉過左左肩斜向前落,落時左手須由胸前化掌穿出為合如「定式圖」

Going along with the lifting of your right leg, your body hops into a left sitting-tiger stance as the saber arcs past your left shoulder and lowers diagonally in front of you, your left hand becoming a palm and shooting out forward from in front of your chest at the same moment that the saber lowers. See photo 45d:

功用:

Application:

此式合卸步,提腿,蹤跳,攔刀,撇刀,拉刀等為一式,若善於運用則合攻守於一矣。

This posture combines a withdrawing step, lifting leg, hop, and the saber actions of blocking, swinging, and pulling into a single technique. If you are good at applying it, then defense and offense will be combined into a single action.

第四十六式 拉刀坐盤式

Posture 46: PULLING THE SABER, SITTING TWISTED STANCE

說明:

Explanation:

循上左,出右脚以成右登山式,刀自後向前劈,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, your right foot steps out to make a right mountain-climbing stance as the saber chops forward from behind. See photo 46a:

再原步不變將刀拉過右後方,左掌仍貼右腕如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then with your stance not changing, pull the saber through to the right rear, your left palm staying at your right wrist. See photo 46b:

再蹤身一跳,以成坐盤之勢,刀自右肩過左肩,沿左臂直落,左手化成刁手,以襯托刀背,如「定式圖」。

Then your body hops into a sitting twisted stance [i.e. your left foot going forward, then your right foot doing a stealth step behind it] as the saber goes past your right shoulder to your left shoulder and lowers along your left arm, your left hand becoming a hooking hand, the arm propping up the back of the saber. See photo 46c:

功用:

Application:

我旣已劈消來械,再進而坐盤以刀攔砍之。

Having chopped away an incoming weapon, I then advance into a sitting twisted stance while slashing with my saber.

第四十七式 中門攔刀式

Posture 47: SLASHING AROUND THE MIDDLE

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,由右轉以成為登山之狀,刀則隨身而轉,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, pivot around to the right to almost make a mountain-climbing stance, the saber arcing along with the turning of your body. See photo 47a:

再將左脚自右脚之前偸過右前方,刀則撇上,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then your left foot does a stealth step forward to the right, passing in front of your right foot, as the saber swings upward. See photo 47b:

再將右脚移往右方,刀則由背部繞過左肩之上,如「過渡式丙圖」。

Then your right foot shifts to the right as the saber arcs around your back to be over your left shoulder. See photo 47c:

再拉起右脚以成左跨虎步,刀再往右上方掠起,如「定式圖」。

Then pull back your right [left] foot to make a left sitting-tiger stance as the saber sweeps upward to the right. See photo 47d:

功用:

Application:

此是專破上門攻來之械,繞行數步者是趨避之法也。

This technique focuses on ruining the attack of incoming weapon to my upper area. The arcing steps are a method of evading.

第四十八式 左門攔刀式

Posture 48: SLASHING TO THE LEFT

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先將左脚往左方移開以成如登山之勢,刀自上劈落以交於前,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your left foot shifts out to the left to almost make a mountain-climbing stance as the saber chops downward from above to go across in front of you. See photo 48a:

再進右脚,刀向上畧舉高,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then your right foot advances as the saber slightly rises up. See photo 48b:

再進左脚,刀循左肩經背部繞過右肩之上,如「過渡式丙圖」。

Then your left foot advances as the saber arcs from your left shoulder around your back and over your right shoulder. See photo 48c:

再進右脚以成右跨虎步,刀自右肩劈過左腰之下,如「定式圖」。

Then your right foot advances to make a right sitting-tiger stance as the saber chops downward from your right shoulder past the left side of your waist. See photo 48d:

功用:

Application:

與四十七式同祗方向之異耳。

Same as in Posture 47, except going in the opposite direction.

第四十九式 右門攔刀式

Posture 49: SLASHING TO THE RIGHT

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,右脚先向右移動,刀由下而掠高於右,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your right foot shifts to the right as the saber sweeps upward to the right from below. See photo 49a:

再過左脚於前方,刀自右繞過背部而復轉於前,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then your left foot goes forward as the saber again arcs from the right to go around your back and in front of you. See photo 49b:

再進右脚,刀由上而落,如「過渡式丙圖」。

Then your right foot advances as the saber lowers from above. See photo 49c:

左脚再斜步進前以成跨虎之勢,刀由下復上以成刀與步之斜式,如「定式圖」。

Then your left foot advances diagonally to make a sitting-tiger stance as the saber again goes upward from below so that both the saber and the stance are in diagonal positions. See photo 49d:

功用:

Application:

與四十七、四十八同,祗斜正及方向之別耳。

Same as in Postures 47 and 48, except going diagonally in a different direction.

第五十式 上步攔腰式

Posture 50: STEP FORWARD, SLASH TO THE WAIST

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先起左脚以成如登山之勢,將刀橫架而起,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your left leg rises to almost make a mountain-climbing stance as you send the saber upward and blocking across. See photo 50a:

再進右脚轉身乃成成左登山式,刀自背後橫過而前,如『定式圖」。

Then your right foot advances and your body turns around to make a left mountain-climbing stance as the saber passes behind your back and goes across in front of you. See photo 50b:

功用:

Application:

與十七、二十四等同。

Same as in Postures 17 and 24.

第五十一式 拉刀收步式

Posture 51: PULLING THE SABER, GATHERING STEP

說明:

Explanation:

循上左,原步不變,左掌向前,右刀目前經過面前拉向背部,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with your stance not changing, your left palm goes forward as your right hand pulls the saber across from in front of you to be behind you. See photo 51a:

再以右後脚跟前如跨虎步形狀,刀循背部沿左臂直落止於腕上,左掌化刁手往後抅去,如「定式圖」。

Then your right foot follows forward to almost make a sitting-tiger stance as the saber passes through behind you and lowers along your left arm until above the wrist, your left palm becoming a hooking hand and hooking away to the rear. See photo 51b:

功用:

Application:

彼擬用長械迫我,我先用左手刁去來械,復以右刀自上而下,以資掩護,亦可作劈擊來械之用也。

An opponent using a long weapon tries to attack me, so I first use my left hand to hook it aside, then send my saber downward from above as a means of shielding myself, or I can also use this action to chop away his weapon.

第五十二式 竄跳囘身式

Posture 52: SCURRYING AWAY WITH THE BODY TURNED

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先將右脚開往東方如登山步,刀與左刁手畧掠開,目注視西後方,如「過渡式圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your right foot steps out toward the east as though to make a mountain-climbing stance, the saber and your left hooking hand slightly sweeping aside. Your gaze is behind you toward the west. See photo 52a:

再原式不變疾跳過西後方,如「定式圖」。

Then while maintaining this position, suddenly hop back [twice] to the west [east]. See photos 52b and 52c:

功用:

Application:

不論已否扣得來械,我皆向後撤退,以便靜觀其變,俟機出擊是也。

Regardless of whether or not I have succeeded in drawing aside the opponent’s weapon, I retreat to watch for what he will do next and wait for the opportunity to attack.

第五十三式 拉刀藏刀式

Posture 53: PULLING THE SABER INTO A STORING POSITION

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,刀與手不變,先進左脚,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, with the saber and your left hand not changing their position, first your left foot advances. See photo 53a:

再轉右東而反向西方提起右脚,左刁手仍抅後,刀則沿右膝部殺落,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then turn around to the right to go from facing toward the east to be facing toward the west as your right foot lifts, your left hand still hooking behind, and the saber smashes down beside your right knee. See photo 53b:

左手與步不讓,刀循前下方繞過背部,右手直舉,如「過渡式丙圖」。

With your left hand and legs not changing their position, the saber follows through forward and downward and arcs behind your back, your right arm rising until vertical. See photo 53c:

乘提右脚之便蹤身一跳,以成左跨虎之勢,刀則轉過左左肩斜向前落,落時左手須由胸前化掌穿出為合如「定式圖」

Going along with the lifting of your right leg, your body hops into a left sitting-tiger stance as the saber arcs past your left shoulder and lowers diagonally in front of you, your left hand becoming a palm and shooting out forward from in front of your chest at the same moment that the saber lowers. See photo 53d:

功用:

Application:

此式合卸步,提腿,蹤跳,攔刀,撇刀,拉刀等為一式,若善於運用則合攻守於一矣。

This posture combines a withdrawing step, lifting leg, hop, and the saber actions of blocking, swinging, and pulling into a single technique. If you are good at applying it, then defense and offense will be combined into a single action.

第五十四式 踏步劈刀式

Posture 54: STOMPING STEP, CHOPPING

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,右後脚用力踏地求與前左脚相貼,再以左掌加於右腕內齊向上舉起,如「過式渡甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, your right foot forcefully stomps the ground right in front of your left foot as your right hand raises up, your left palm going to the inside of your right wrist. See photo 54a:

再開進左脚以成左登山式,刀自背後直砍而出,左掌則橫架於頂如「定式圖」。

Then your left foot advances to make a left mountain-climbing stance as the saber chops out from behind you, your left palm blocking across above your head. See photo 54b:

功用:

Application:

來械直向我面部刺來,我先以刀橫去之,再乘勢以直劈法還擊彼面部焉。

An incoming weapon is stabbing to my head, so I first use my saber to send it aside, then follow through with the motion by doing a chop straight ahead to counterattack to the opponent’s face.

第五十五式 拉刀四平式

Posture 55: PULLING THE SABER, FOUR-LEVEL POSTURE

說明:

Explanation:

循上式,先提右脚,刀沿脚傍撇下,左掌仍不動,如「過渡式甲圖」。

Continuing from the previous posture, first your right foot lifts as the saber swings downward beside the foot, your left palm not moving. See photo 55a:

再原步不動,刀從下轉上以加於左臂之上,如「過渡式乙圖」。

Then with your stance not changing, the saber arcs upward from below to go on top of your left arm. See photo 55b:

再原步不動,左手捧囘原刀,左掌向大腿處拍落,如「過渡式丙圖」。

Then with your stance still not changing, your left hand holds the saber as it did at the beginning and your left [right] palm comes down, slapping your [right] thigh. See photo 55c:

再退提起之脚以成左跨虎步,右掌轉而向上橫架於頭頂,左手刀向後斜拖,如「定式圖」。

Then your lifted leg retreats to make a left sitting-tiger stance as your right palm arcs upward to block across above your headtop, your left hand pulling back the saber until it is diagonal behind you. See photo 55d:

斯為收式之刀法,全刀五十五式至此已還復本來面目。

This is the closing posture of the saber set, bringing you back to your original position and facing the same direction as before.

– – –

[Included below is a related piece from Huang’s Notes on the Mantis Boxing Art (1951).]

單刀搜秘

SECRETS OF THE SINGLE SABER

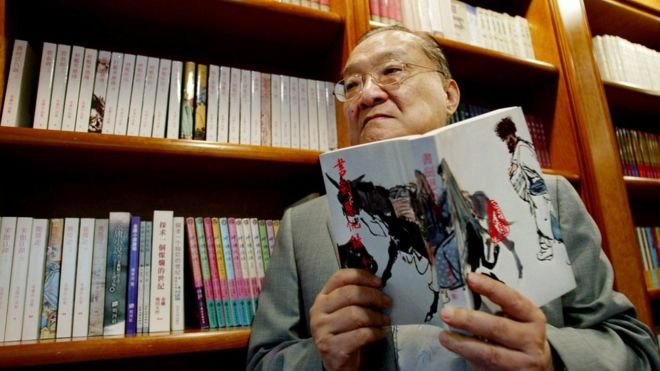

昔者武壇多譽先師全才,蓋先師當日除擅拳法、鐵砂掌外,各種武器靡不精研,尤以單刀一類有所獨到,唯不趨尚時髦、討好觀衆,雜以滾地等動作,謹守武術界之尊嚴,余習藝時曾蒙以十法見示,十法者劈、軋、抅、掛、削、拍、挑、撩、搜、撈是也。考刀術為各種武器中之最繁雜之一,唐以前用刀者俱為長桿子之大砍刀(即俗稱之大關刀),此名之由來,實因武聖用刀且姓關之故,至宋室中葉,水滸英雄武松與浪子燕靑俱以步戰馳譽,前者固以行者棒號稱天下莫敵,後者却以單刀得名,故至今有燕靑單刀之技傳於世。

大砍刀、單刀、斬馬刀之外尚有雙刀,世人不察每以雙刀比單為難,其實雙刀之為用,祗兩手平均、步法靈活便可運用自如,其法甚簡單而已。

單刀看手一語,為單刀之心法,亦為單刀中之至難安置之處,試觀夫稍懂一、二者常自詡為精於單刀法,然其演習時又常常刀與手脫節,全不注重刀與手之配合,其能謂之於精乎,即為舞台上當生旦對答之時正在悠揚悅耳之表情與動作同時演出,使觀衆全神灌注,當斯時也甚少人注視其背後所飾演之童僕之形狀,若空無所握之左手即等於童僕耳,若不有所動作便形同虛設,更且陷於本身痲痺之狀,若說實用更無所扶襯相托矣。

練刀之法除刀與手互相動作毋使一方有所停滯之外,尚須刀與身貼,步隨勢移方為刀之正法,刀如猛虎一語實形容其勢雄猛之處,又曰拼命用單刀之說,凡以單刀臨陣應敵者苟存恐懼之心,無不為敵所敗,蓋單刀為短兵刃,若與長兵械相接,其勢固拙,瑟縮不前者必為長械所乘無疑,但立拼命之心長者為我所接,則我一躍而前,長短之勢有所平合,勝敗之機互握半數,若更因勢利導,緊握時機,敵為我乘,則其敗立判矣,今之練刀者苟能髓味斯旨,距成功之域近矣。

Master Luo’s versatility was often praised in martial arts circles. Beyond his mastery of boxing methods and iron palm skills, he had intensively studied various kinds of weapons, becoming uniquely adept at the single saber in particular. But as he did not care about what was popular or what would impress an audience, he did not mix in tricks like rolling around on the ground, concerned only with preserving the dignity of the martial arts world. When I learned this art, it was presented to me as being comprised of ten techniques: chopping, rolling, hooking, hanging, slicing, patting, carrying, raising, searching, and scooping.

Examining the saber arts shows it to be one of the most varied of the many weapons. Prior to the Tang Dynasty, the “sabers” used were all long-pole large cleaving sabers, what is commonly called the large “Guan Saber”, so named because it was used by the martial sage Guan Yu. During the middle period of the Song Dynasty, “The Pilgrim” Wu Song and “The Wanderer” Yan Qing, heroic characters from The Water Margin, both became famous for their martial deeds. The former used a staff, with which he was considered to be invincible, while the latter became known for his use of the single saber, after which is named the “Yan Qing’s Single Saber” set that has been passed down to us to this day. Beyond the large cleaving saber, single saber, and horse-slashing saber, there is also the double sabers. Most people do not scrutinize and simply assume that the double sabers are more difficult than the single saber. Using the double sabers is actually only a matter of both hands working evenly and the feet stepping nimbly, and then you will be able to wield them smoothly. Its techniques are really very simple.

There is a saying: “With the single saber, be mindful of your other hand.” This is a core principle of the single saber, as well as the most difficult aspect of it. Observe someone who understands the art very little and yet often brags that he is an expert at the single saber. When he performs, his saber and left hand constantly lose coordination between each other, and he never pays attention to having cooperation between them. How could he be considered an expert? When a dancer on a stage begins to sing, and her sweet singing is performed in tandem with her movements, the audience becomes rapt with attention. In that moment, very few people would notice the stagehands in the background. If the saber practitioner’s left hand is so uninvolved that it becomes like one of those invisible stagehands, or if it is moving with so little purpose that it almost turns into some paralyzed appendage, then it will seem to be of no real use at all.

When practicing the saber methods, beyond the saber and hand coordinating with each other rather than either of them becoming sluggish, the saber has to move close to the body, and the step has to shift along with the movement in order for the saber’s techniques to be precise. This saying expresses well the required quality of fearsomeness: “The saber is like a fierce tiger.” There is also this saying: “Defy death as you wield the single saber.” Whenever you use the single saber to battle against opponents, if there is fear in your heart, you will always be defeated. Because the single saber is a short weapon, if my saber connects with a long weapon, I would of course be in an awkward position. If I am then too timid to go forward, his long weapon is certain to have the advantage, but if instead I have a mentality of defying death, his long weapon will then be under my control. Therefore I charge in, leveling the odds between long and short, grasping the decisive moment between victory and defeat. Treating half a chance as more than half, I act in accordance with the situation, seize the opportunity, and take advantage of the opponent’s position, and thus his defeat becomes a more likely outcome than mine. If you modern saber practitioners can deeply think upon this point, you will be much closer to success.

–

–

–