***One of my goals in creating Kung Fu Tea was to inspire more enthusiasm for (and participation in) the scholarly discussion of martial arts. As such, I am happy to share a reader’s lengthy response to a recent essay. After seeing his original comment I felt that it could be expanded to make a great guest post. My original essay was a thought experiment in which I tried to applied a single signature concept of the Peace Studies literature to the discussion of martial arts. This approach to International Relations (my home field) tends to be much more popular in Europe than the US, and I wanted to see what what would happen if I approached thing from a slightly different angle. But all of this inspired Frank Landis to present some ideas of his own. Enjoy!***

Nonviolence and Martial Arts Studies

By Frank Landis

I appreciate the chance to write a guest essay on a blog I’ve read for years. This post is in response to ”Violence and Peace: Reconsidering the Goals of Martial Arts.” It’s an expansion of a comment I wrote on that post. Simply put, I believe that it might be more useful to analyze violence in the martial arts among multiple dimensions, rather than a single dimension of peace-to-violence, as Ben proposed in that piece.

First some background: who am I?

I’m not a martial artist, although I was one of the vast multitude of indifferent students of several martial arts some decades ago. These days, I just practice qigong and meditation. Professionally I am a writer and environmental activist, and I happen to have a PhD in Ecology. This last fact is quite relevant: we ecologists tend to be “statistical bottom feeders,” in that we have a strong tendency to swipe analytical methods from other fields, rather than inventing our own. In my work, I’ve used a number of sociology techniques to analyze data. Even though I’m not a sociologist, I’m somewhat familiar with sociological methods, at least so far as I have learned and applied them to my own work.

The central question, as I see it, is whether it’s more useful to look at the diversity of martial arts, and their place in society, along a single dimension, with peace at one end and violence at the other, or whether it’s more useful to look at multiple dimensions and a multidimensional cloud of possibilities. Keeping explanatory dimensions as simple as possible is ideal, but simplification breeds confusion when a single explanatory dimension lumps together phenomena that do not have much in common. A multidimensional approach opens up a more complex space in which to look for explanations and patterns. However, if there are too many dimensions (say, one dimension per case), then the complexity is useless: every case is unique and unrelated to the others. The sweet spot is a system of dimensions that’s complex enough make patterns and relationships obvious, but simple enough to be able to construct explanatory (and dare we hope predictive?) narratives from the patterns we find.

The other relevant part of my background is the 2016 US Presidential election. I am very much not a supporter of the current US regime, and after the election, I started reading the literature on nonviolence. My reasons were simple. I figured I had good odds of getting involved in protests (and I have), and I wanted to understand the theory and practice of nonviolence well enough that I might actually be useful. At minimum I wanted to avoid being suckered into joining a badly organized, useless, exercise. As an environmentalist, I know all too much about those. So I’ve done a lot of reading and a lot of thinking about both nonviolence and martial arts. That is what I present here.

Now, about nonviolence in a martial arts context. Why should any martial artist care about nonviolence? There are two answers. One is to look at the commonalities. Both nonviolent actors and martial artists need to be able to absorb an attack and maintain discipline. For example, imagine a 70 year-old grandmother who’s out protesting and gets beaten by the cops. Turns your stomach, right, that helpless old lady being clubbed by guys wearing body armor? That visceral feeling is the power of nonviolence, and if people witnessing the beating are turned against the people doing the beating, that little old lady has won her fight. Theorists of nonviolence call that “political jujitsu.” A little old lady may not be able to strike back, but paradoxically, by being willing to suffer for her cause she can win, even when she’s being dragged off to jail. That willingness (and discipline) to suffer to one’s attain goals unites many nonviolent actors and martial artists.

The second reason martial artists may want to care about nonviolence comes from Chenoweth and Stephan’s Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. In their analysis of hundreds of conflicts from the last century, movements that used nonviolent tactics were twice as likely to reach their goals as were those that used violence (52% to 26%). While their database includes great nonviolent victories like Gandhi’s expulsion of the British from India, as well as great defeats like Tiananmen Square, on the local level, it is the utility of nonviolence which explains why workers almost always choose to strike, rather than to physically attack their employers or work places. Striking is not about weakness, it’s about efficacy. A big part of what makes nonviolent action so efficacious is that everyone, from children to little old ladies, can take part. In contrast, the percentage of the population that can (or will) get involved in violent attacks is much smaller, requiring greater physical fitness or training. Returning to the subject at hand, the theories explaining the utility of nonviolence, especially those of Gene Sharp and his followers, can be usefully applied to the study of martial arts in the wider society.

For the sake of discussion, I propose there are four dimensions related to peace and violence in which hand combat might be considered, although the fourth is peripheral to most modern martial arts.

One dimension is about the exercise of physical power, with nonviolence at one end of the spectrum and violence at the other. This is an extension of what’s conventionally termed the “use of force continuum.” Most of us are familiar with the concept, espoused by many police departments, as a rational for how they justify the use of force.

The US Navy version of this continuum (from nonviolent to violent) is “Officer presence, Verbal commands, Soft controls, Hard controls, Intermediate weapons, and Lethal force (per the link above). I would suggest that this continuum extends both on the nonviolent end, with a huge diversity of nonviolent tactics beyond presence and verbal command that includes Sharp’s list of 198 tactics. I would also suggest that the lethal force end of the continuum extends well beyond what police deploy, with all the variations of lethal force practiced by militaries up to nuclear war.

One thing to realize is this dimension isn’t about what trumps what. To use an absurd example, police officers don’t make arrests by walking around with nuclear warheads and threatening to detonate them if people resist arrest. More specifically, the use of lethal force against nonviolent protestors is generally considered so abhorrent that a nonviolent campaign can use “political jujitsu” to leverage a regime’s inappropriately scaled response to effectively delegitimize its grasp on political power. Instead, this dimension covers the diverse kinds of conflicts, from debates to shouting matches to wrestling to fist fights to knife fights to gun battles to artillery battles and beyond.

On this dimension, martial arts occupies a space in the middle, focusing on what the police consider soft controls, hard controls and intermediate weapons, and tapering gradually into both lethal force and nonviolent training. It’s worth realizing that the wider, political world occupies a much bigger space, with entities from governments to corporations, gangs, and activist groups, being involved in both nonviolent and explicitly violent means of using and supporting their social or political power.

The second dimension is explicitly derived from the late Gene Sharp’s analysis of how nonviolence works. He outlines two models of the origin of political power: top-down and bottom-up. Top down power is imposed from above, by conquest, or justified by the divine right of kings, the Mandate of Heaven, and various other authoritarian theories. At the other end of the dimension we see bottom-up approaches where people claim their own power and manufacture their own organizations without aid from above. This is a dimension and not a dichotomy, in part because when grassroots groups are fighting entrenched and unjust governments, one of their essential steps has to be pulling powerful groups, like big business and the military, onto the side of the protestors and away from supporting an unjust government. I’d argue also that bottom-up and top-down often meet in the messy middle, and that the people and organizations with some power occupy this middle and influence both the established order and the people who want to change the system.

Sharp’s analyses focus on nonviolence in the context of “bottom-up” struggles, of people who are not in power finding ways to bend the authorities to their will or to disempower existing governments. This is a vital analysis, but in linking nonviolence with bottom-up power structures, Sharp’s analysis ignores all the ways that nonviolence is promulgated through top-down strategies. These include states conventionally monopolizing the use of force and constraining their citizens to less violent or nonviolent actions, and to all the ways that states promulgate order and peace as memes, ethics, and norms. There’s a reason that ambassadors spend time talking with each other: generally it is more effective than starting with an armed assault and then de-escalating when the sides reach a stalemate.

In the context of Chinese martial arts and history, it appears to me as a nonexpert that both Confucianism and Daoism, at least rhetorically, promulgate ethics of peace and justice, and see war as justifiable only in the context of what we in the West would call a “just war.” While this is a gross oversimplification that ignores a lot of history and culture, it does point out the utility of having two dimensions of political power: one being the continuum of force and one being top-down versus bottom-up power. Chinese martial arts seem to be on the more-violent and bottom-up side of the graph, as opposed to a government that is top-down and at least rhetorically nonviolent, except where violence is required to restore order and justice. Having these two dimensions also allows us to look at how martial arts are affected by middle men and power brokers, nobles that raise militias, magistrates who defend towns using martial artists, and similar situations.

The third dimension runs from performance to practical application. The military is on practical application end of the spectrum. Uniformed troops on parade, or doing demonstrations, are certainly engaging in an act of public performance, but soldiers were also supposed to be willing and able to use lethal force to end political conflict. On the performance end of the spectrum we might find martial arts sets like The Drunkard’s Kung Fu that Leung Ting published decades ago. It’s impractical for fighting, but certainly entertaining to watch. Such a set serves a functional goal when a performer can use it to make money and eat.

There’s a whole range of intermediates possitions in the martial arts world along the spectrum from performance to practical application, and they have different uses that are integral to the survival of many martial arts. I think that most people would rather perform cool sets and possibly intimidate their way out of fights, and very few would rather practice actually killing their opponents. It seems that martial arts styles that only trains its students to maim or kill their enemies (and hopefully not each other) generally have far fewer students than ones that teach other socially acceptable skills like discipline, fitness, and ethics.

While this dimension alludes to the endless debates about which school is better in the octagon or on the street, or whether a set is dead or alive, it doesn’t provide answers to those debates. So far as I’m concerned, both performance and practicality have different and vital functions. The point is to understand the existence of diversity, not to rank it. On the nonviolent side, there seems to be a similar diversity ranging from big, flashy, useless rallies (on the performance side) to targeted effective strikes (on the practical).

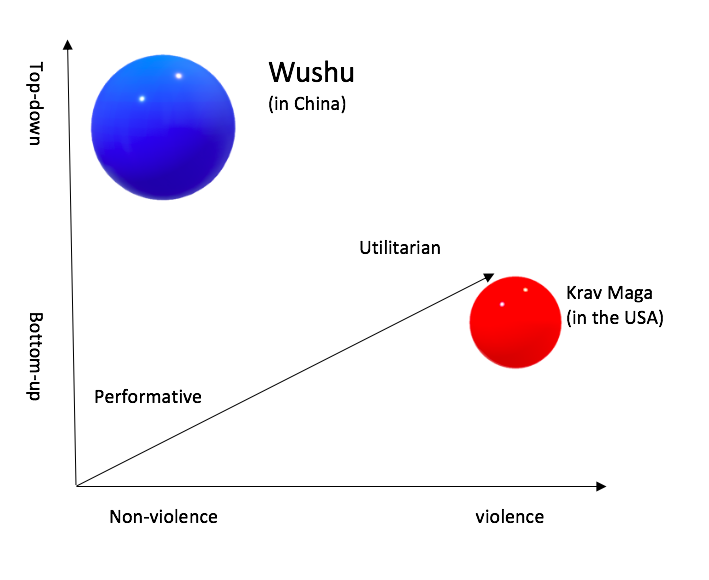

When we start looking at martial arts in three dimensions, we see a real diversity: for example, there is wushu, which is driven by the top-down politics, relatively nonviolent, and performance focused. There are mixed martial arts, which are more bottom-up, occupy the nonlethal violence part of the continuum, and are fairly practical about the mechanics of forcing people to submit. Then there are systems like William Paul’s nonviolent self-defense. This system, used most often in hospitals, is nonviolent, practical, and in the middle of the top-down/bottom-up spectrum, since it is usually taught within medical institutions as on-the-job education. If you’re not familiar with this system, it teaches medical professionals to protect themselves from patients and family members who are threatening or acting out violently. The goal is not to hurt the violent people, who may be delusional or extremely upset, but for practitioners to deescalate if possible, get out of the situation while minimizing the chance that they get hurt, and at most to restrain people without hurting them.

These three dimensions also allow us to talk about the evolution of martial arts over time. At least according to their origin stories, they often begin as individuals protecting themselves against an unjust world (e.g. bottom-up, fairly violent, and practical), and evolve as they grow to become more institutionalized, often more performance based (with sets replacing sparring, or empty hand fights replacing weapons), and sometimes less violent (focusing on keeping students out of trouble as opposed to helping them win fights). All of this may be vital fir keeping schools open and attracting students. For example, the evolution of Wing Chun could be seen from the bottom-up perspective focusing on the practical application of hard controls and lethal force to the problem of self defense in a region where the state’s monopoly on violence had broken down. But where the art has survived and the school(s) grew and spread by colonizing more performative and less explicitly violent and more explicitly legal spaces.

There is a fourth dimension, but martial arts tend not to diversify along it. That dimension is about organization, with individuals at one end and large organizations, like armies and movements, at the other. Martial arts tend to focus on the development of individuals. It is comparatively uncommon for martial arts schools to teach formation fighting or how to organize small units, let alone how to organize big campaigns strategically. However, organization is critical for both military and nonviolent campaigns, and it is what military officers are taught in their schools and nonviolent leaders learn from their instructors.

While organizing small-unit tactics isn’t hard—witness everyone from the Society for Creative Anachronisms to nonviolent protestors, the antifa, and the alt-right all reinventing shield walls—it’s not part of what most martial arts schools teach. At most, organizational training in the martial arts is on the level of the capoeira roda, organized skill demonstrations and tournaments, newsletters on the profitable running of dojos, and the like. Still, organization is an important dimension for analyzing the exercise of power in wide variety of milieus, so I’ll pitch it out there for people to think about in the context of martial arts.

Violence in martial arts can more usefully be discussed and analyzed with reference to three or four separate dimensions, rather than one. Like all models these are ideas worth playing with only to the extent that they are useful, and it is in that spirit I’m offering them to anyone who might find it worthwhile. Thanks for this opportunity to present it.

oOo

If you enjoyed this guest post you might also want to read: Love Fighting Hate Violence: An Anti-Violence Program for Martial Arts and Combat Sports

oOo