What is my motivation?

Connecting the dots between an individual’s intentions, their actions and subsequent systemic outcomes is more difficult than one might suspect. Just ask any social scientist. Understanding each of these categories is important if we want to come to terms with either the causes, or interpretive meanings, of any event. Yet the structure of the social world dictates that none of us get to work our will just how we would like. My desires may bump up against your goals, and suddenly we both find ourselves acting “strategically.” As the environment becomes complex, everyone is forced to do things that are not reflective of their original intentions. Often this brings about situations that no single actor intended.

This is how you get major interstate wars, at least according to a number of leading scholars in the discipline of International Relations. Given its excessively costly nature, great power war is often modeled as a type of miscalculation. Or as one of my old teachers put it “War is the error term.” We could say something similar about lots of bad outcomes. There is not a single super-villain out there devising a plan to pollute the world’s oceans with plastics. Rather, lots of people make individual choices about personal consumption, or corporate policy, and the end result is something that no one individual truly intended. Such is the tragedy of the commons.

This leads us to one of the most important realizations to emerge from the field of Political Science (and before that Philosophy). Our fellow humans are responsible for many of the bad things that seem to define life, yet none of them (or very few) are actually evil. Even fully rational people seeking their own self interest will inevitably fall into conflict and probably violence. And that is a best-case scenario. To make matters worse, students of psychology have determined most decision making is no-where near “rational.”

Violence is pervasive. It takes many forms. There are short, sharp, instances of acute physical violence. Wars, or physical assaults tend to get the most press. But I don’t think there is any evidence to suggest that in total they are really more destructive than the other forms of structural violence that humans wreak on each other. Famine, disease, colonialism and addiction have all taken their toll. But at least we can still quantify things like infant mortality rates (which typically go up in civil wars) or life expectancy (which tends to drop when economies go into a serious prolonged crisis). Harder to measure, though no less real, are social stressors like inequality, discrimination and humiliation.

The martial arts interest me as a social scientist for many reasons. Yet one of the most powerful is that they are a relatively inexpensive tools which local societies, across the globe, turn to as they seek to address the effects of violence in their own communities. It wasn’t really until the 1960s and 1970s that social scientists in the West began to diversify our understanding of violence as having more than just a physical or political dimension. Yet already in the 1920’s we can read book after book, article after article, in which Chinese martial artists argued that their practices could insulate the nation from each of the ills listed above. They seemed to be far ahead of the curve on this.

This is also part of our challenge when we try to study the Chinese martial arts. As I have argued before, it is impossible to reduce Chinese hand combat down to a single set of motivations. Many people have practiced these systems for many different reasons. An imperial bannerman, a night watchman, an opera performer and a traveling medicine salesman may all have practiced some sort of kung fu in the year 1819. While they all may have done this so as to “make a living,” the sorts of violence that they faced (structural or otherwise) was not exactly the same.

Giving Peace a Chance

Over the last few years Paul Bowman and I have, at different times, called for greater focus on the problem(s) of violence within Martial Arts Studies. Some of the things that have already been written suggest that students of our field can bring very interesting perspectives to these discussions. For instance, I highly recommend that everyone take a look at Sixt Wetzler’s chapter in the recently published Martial Arts Studies Reader as a great example of the unique type of work that we might be able to do.

But while violence is the drumbeat that structures so many people’s lives, it is not a concept that can be understood (or even exist) in isolation. As a result, we may not be able to fully grasp the social work that the martial arts are called on to perform if we examine them only in relation to this concept. Most frequently, violence (or in its interstate form “war”) is placed in opposition to the concept “peace.”

I put peace in quotes for a very good reason. The complexities of defining and conceptualizing violence pale in comparison to the challenges of understanding peace. Violence is, after all, encoded in things that are done or structures that exist. Peace is a subtler matter. Yet it is critical as it structures the motivations of a good many martial artists, in a huge variety of times and places.

Perhaps the easiest place to start would be with a distinction drawn within the Peace Studies literature, often attributed to Johan Galtung. Still, it should be noted that these terms have been in circulation since the start of the twentieth century and reflect a common pattern of conceptual classification seen throughout the field of Political Science. Galtung notes that “negative peace” is often taken to mean the absence of violent acts. Importantly, it does not actually suggest a lack of conflict. For example, Russia and the United States enjoyed a negative peace during the Cold War. Though their conflicts continued to have a shaping effect on global politics, and terrified generations of people with the prospects of nuclear annihilation, no actual shooting between the two super powers ever took place. Clearly this is a type of peace, but it is one that leaves something to be desired. Even in the absence of a formal declaration of WWIII many people’s lives were destroyed.

The stark nature of this paradox led to renewed focus (first in Europe, and to a lesser extent in the United State) on the idea of “positive peace” in the 1960s and 1970s. It sought to move beyond the obvious violence to address sources of underlying conflict (where possible). This often means creating new types of relationships between actors, or internally seeking to address the systemic social and economic failures (poverty, famine, alienation, inequality) that either led to conflict in the past or might simply rob people of their basic humanity going forward. Advocates of change through the creation of positive peace are typically just as interested in what is happening in the World Bank as the UN Security Council.

Peace Studies departments are much less common in the United States than the sorts of International Relations (IR) programs where I received my training. Still, a number of their concepts have found their way into the general Political Science literature. One of these insights, which might be particularly helpful for students of Martial Arts Studies, bears on the question of scalability. Much of the traditional IR discussion of violence has focused on events at the national level. After all, nations which go to war and IR theorists very much want to understand why.

But a moment’s thought suggest that it is not just nations that “go to war.” It is also social groups, cities and individuals who are mobilized in these campaigns. And it is at this much more local level that the violence of a conflict, whether acute or structural, is actually absorbed. We should not be surprised to discover that local leaders and community actors are often very aware of the logic of negative and positive peace.

Peace Through Strength

Still, local community leaders have neither the resources nor the ability to make the sorts of sweeping systemic changes that classical Peace Theory often advocates. Instead they may find themselves relying on voluntary groups as they attempt to steer their communities through events not of their own making. This is one area, from Japan to Indonesia to South America, where we have regularly seen martial arts communities brought into the political realm.

For instance, one of the most common side effects of sudden economic or political disruption is a spike in violent crime. At various times in Chinese history martial arts groups have been explicitly called upon by local officials to deal with these trends. They have been used to clear the roads of bandits, protect crops ripening in the field from neighboring villages and even to form militias. Or to put it slightly differently, the martial arts societies were called upon to provide some much-needed “negative peace.” In the short run one must protect the village’s crops and keep bandits at bay before anything other sort of policy action is possible. Likewise, when we train individuals to physically protect themselves from the worst effects of a violent assault in a modern American environment, we are focusing on a model of negative peace. We are attempting to bring peace by ending an anticipated attack.

Yet that was never the only goal of the Confucian officials who would, from time to time, recruit martial arts groups to help and restore order in the countryside. They were well aware that violent bandit groups tended to recruit from the same pool of “bare sticks” (young unmarried men with few economic prospects) that martial arts schools drew on. In times of famine or economic disruption these individuals, who were typically day laborers or only marginally employed, were hit first and hardest by any disruption. That hunger and desperation was precisely why they were likely to join a bandit organization. Worse yet, they lacked a secure place within the traditional village structure which defined one’s status through the inheritance of land, marriage or educational attainment. The long-term social prospects for excess sons was quite bleak. Or in current social scientific parlance, we might say that these young men were systemically disadvantaged.

The formal raising of militias, or the informal tolerance of martial arts groups, addressed these issues on two levels. Militia membership came with a paycheck that might forestall economic emergency. Membership in a martial arts society provided an important source of identity. There individuals would develop narratives about the importance of protecting the same communities (and according to Avron Bortez, even the same norms) which might otherwise have been seen as alienating and threatening. In either case, by taking young men off the street the bandits brotherhoods and rebel armies had fewer potential recruits and they tended to grow more slowly. This, in turn, limited their ability to disrupt the peace.

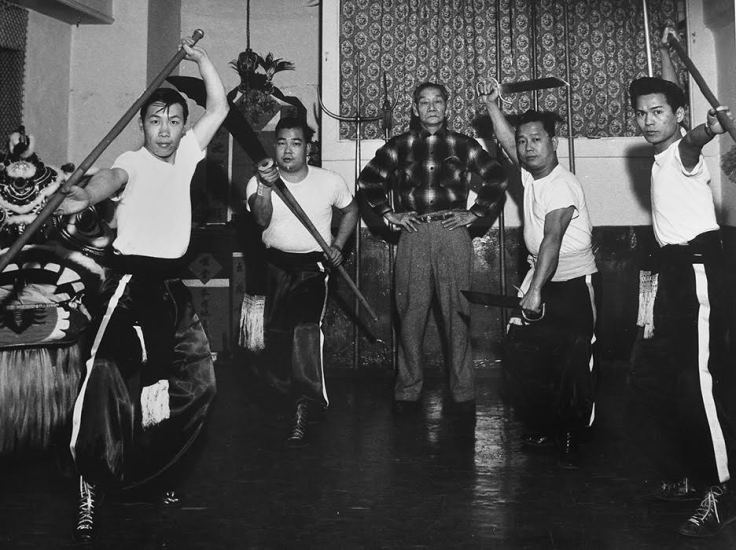

All of this reveals an important pattern. Martial artists, while lacking standing within the Confucian order, were often a critical asset necessary for the stabilization, and projection of power into, local society. In times of crisis it really was necessary to “man the barricades” and fight bandits. Hence the actual efficacy of these practices were important when thinking about the strategies for imposing a “negative peace.” Yet these measures worked best when they succeeded in convincing young men that they had a place in the system, forestalling the rapid expansion of the types of social disorder that arose quite frequently in Chinese history. And it is not at all clear that the “most realistic” types of martial arts training would serve these other ends the best. Basic fitness and self-defense skills are always great. More importantly, they transform violence from an existential threat to an engaging puzzle that one can organize their training and identity around. And if the creation of a positive peace is your central goal then public performance (lion dance), community building (lineage mythology) and ritual begin to make a lot more sense.

When viewed from the perspective of negative peace these things may appear to be secondary considerations at best. Others might see them as distractions, or evidence of the “decayed” state of a martial system. And yet these “secondary” practices and structures must also be replicated through the generations, often at great expense. So why maintain the effort? Why do so many systems continue to argue that the martial arts are first and foremost a means by which young people learn about their place in society? If we consider these same systems from the perspective of positive peace theory suddenly these sorts of practices make much more sense. Rather than being somehow secondary they are important tools by which local society seeks to address the sorts of ills that lead to festering conflict and eventually violence.

Conclusion

Most of this post has been framed as a discussion of how we might relate these two different concepts of peace to understanding the motivations of martial artists in late Imperial China. Anyone who wants to read more about these strategies need look no further than the classic academic works on the Boxer Uprising (Esherick) and the Red Turban Revolt (Wakeman). Indeed, the Late Imperial Chinese literature is full of accounts of local elites running through these exact strategies as they sought to utilize (or contain) the potentially violent power of large groups of disaffected young men.

Yet these two understandings of peace, and the strategies that are employed to achieve it, are valuable precisely because of their portability. Young people living in violent neighborhoods may seek out martial arts training because they fear physical violence, and in so doing find kung fu schools or Olympic boxing programs that have specifically designed by local community leaders to provide “at risk youth” with the sort of tools and social support that they need to succeed. The Salt Lake City library recently instituted a Taijiquan program for the local homeless population in an effort to deal with some of the structural, rather than physical, challenges that this community faces. One could multiply examples like this almost endlessly.

I have written at length as to how our current martial practices are a product of modernity, rather than some mythic past. I don’t want to rehash those arguments here. But it is worth remembering that one of the central defining aspects of modern economic markets is a tendency towards ever more narrow forms of specialization. Lawyers, medical doctors, teachers and psychologists now handle the same functions that monks or priests once did. And in general, they do so much more efficiently as they are allowed to spend their entire careers focusing on a single task. I think that we also see a certain tendency towards specialization within the martial arts community. Certain schools focus intently on developing “real world” fighting skills for the realm of combat sports, while others seem to specialize in teaching 6-12-year-old students core social skills like “discipline” and “focus.”

Still, the martial arts community is one place where you do see some resistance to this trend of ever greater specialization. In some cases that resistance seems to be a cause of frustration. Within my own style it is not hard to identify the groups who want to see more emphasis on the combative western approach to sparring and others who are only interested in form work and delving into the “inner” aspects of their art. Yet angry snipping on internet forums aside, at the end of the day everyone is still doing Wing Chun.

Social scientists might be tempted to see this resistance to specialization as a rejection of modernity. A few might even (incorrectly) interpret it as evidence of the survival of “pre-modern” social structures into the current era. That sort of theorizing might be premised on the unstated assumption that martial arts styles, or even individual practitioners, have a single dominant goal or interest. If that were the case, then perhaps a resistance to technical specialization would be a sign of some sort of “social discourse” overwhelming the logic of market rationality.

Yet the existence of negative and positive strategies for achieving peace and harmony in our communities (at whatever level we choose to define them) suggests that there may be some very good reasons why so many traditional martial arts have refused to specialize. In our enthusiasm for our individuals training we often lose sight of the fact that these systems are fundamentally social in nature. And it is very difficult to know in advance which threats of violence a group or community might face decades in the future. Southern China in 1850 faced the prospects of both civil war and invasion by foreign powers. In 1950 the main challenge facing youth in Hong Kong was social dislocation and the unique cultural pressures that come from living in a system of simultaneous exile and colonization. Remarkably community, leaders turned to similar martial arts as a critical tool in addressing both sets of problems.

As a student of Martial Arts Studies all of this is endlessly fascinating and very instructive. Yet I also suspect that there is a lesson here for me as a student of traditional Chinese martial arts. While I am always seeking to clarify my own practice, perhaps I should be more comfortable with the fact that many traditional fighting systems insist of inhabiting the messy middle. What at first appears to be a crisis of utility (“But will it work in the Octagon?”), might in fact be the very thing that allows these systems to deal with the many other sorts of structural violence (isolation, inequality, disease, discrimination) which leads many students to seek a more meaningful sense of peace in their lives.

oOo

If you enjoyed this essay you might also want to read: Telling Stories about Wong Fei Hung and Ip Man: The Evolution of a Heroic Type

oOo